For four decades it has garnered a reputation for daring deals and outsized returns; an exclusive domain where the choicest opportunities are available only to the richest and best-connected players. But private equity and other lucrative forms of private market investment are widely tipped to be ‘democratised’ over the next decade, opening up trillions of dollars of opportunities for somewhat more humble investors.

‘Why should only the wealthiest have the broadest access to investments?’ asks Joan Solotar, the New York-based executive charged with broadening that net at Blackstone, the world’s largest alternative asset manager.

Power to the individual

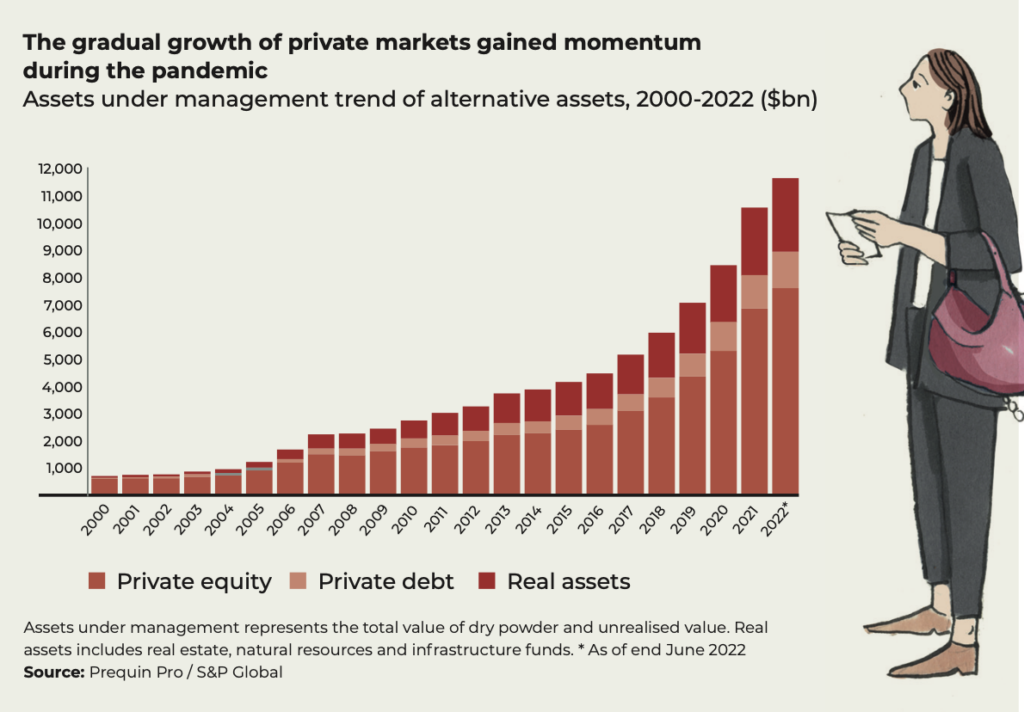

Many in the industry agree that the private markets – investment vehicles beyond publicly listed stocks and bonds – are poised to double or even triple from their current size of about $10 trillion, as the number of publicly listed companies continues to fall. And with many fund managers struggling amid higher interest rates and tighter monetary policy to raise money from their normal sources such as pension funds, sovereign wealth funds and university endowments, it is clear that individual investors will become a much more important source of capital for private markets.

[See also: How ‘intro-fluencers’ are looking to profit from family offices]

Regulatory changes are gradually lowering the barriers to individual involvement in the sector, and a steady flow of new products and distribution methods is helping to lower the entry price from the millions of dollars to something closer to $10,000.

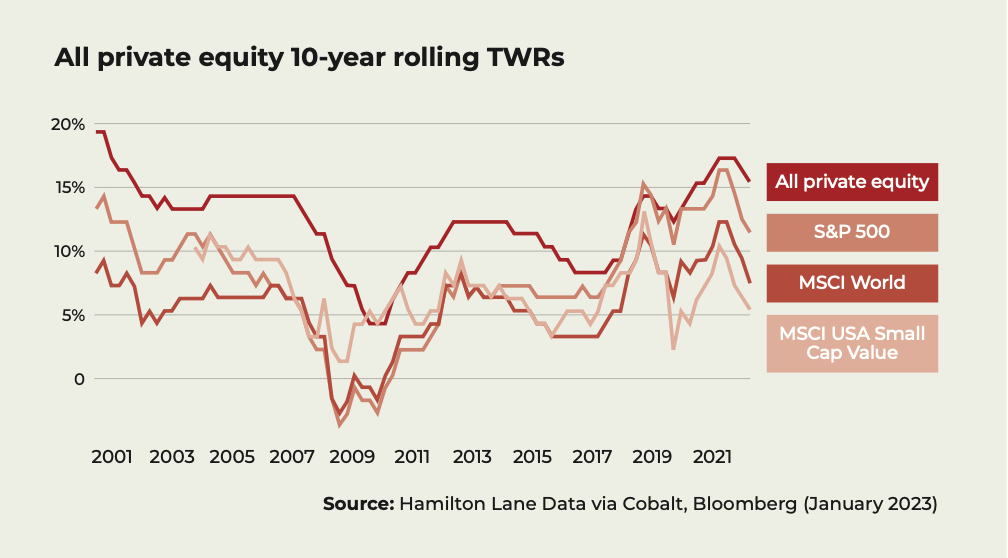

According to the MSCI World Index, private equity globally has returned an annual 14 per cent over the past 25 years, compared to 7 per cent for public markets, so giving mainstream individual investors access to those returns, and other ‘alternative’ investments such as private credit, real estate and infrastructure could be a badly needed opportunity for all concerned.

The ‘end of an era’ for private equity?

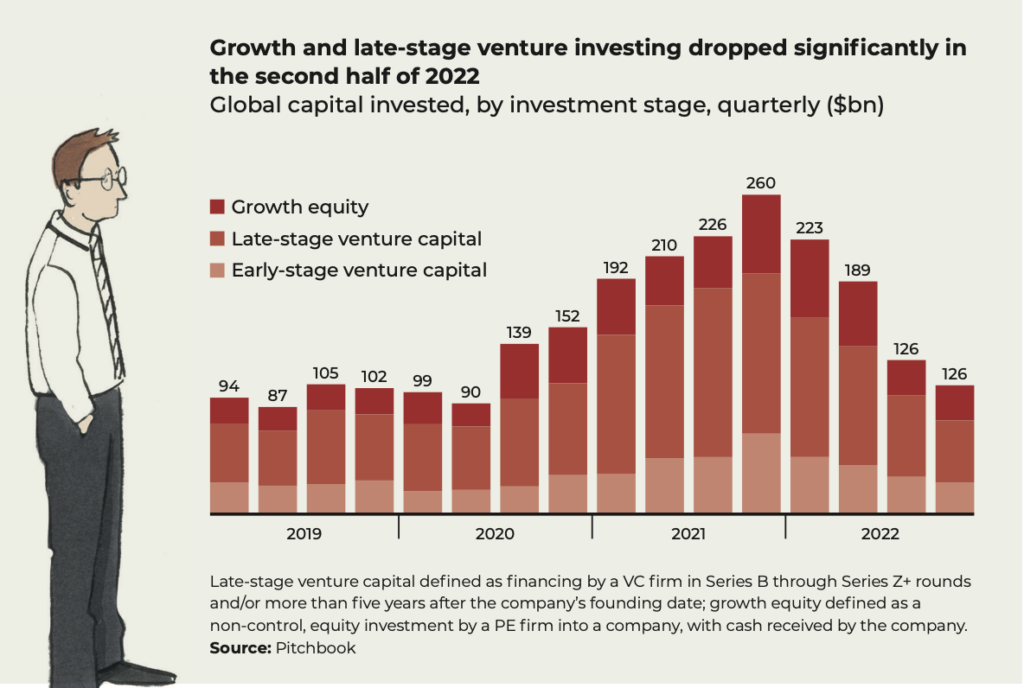

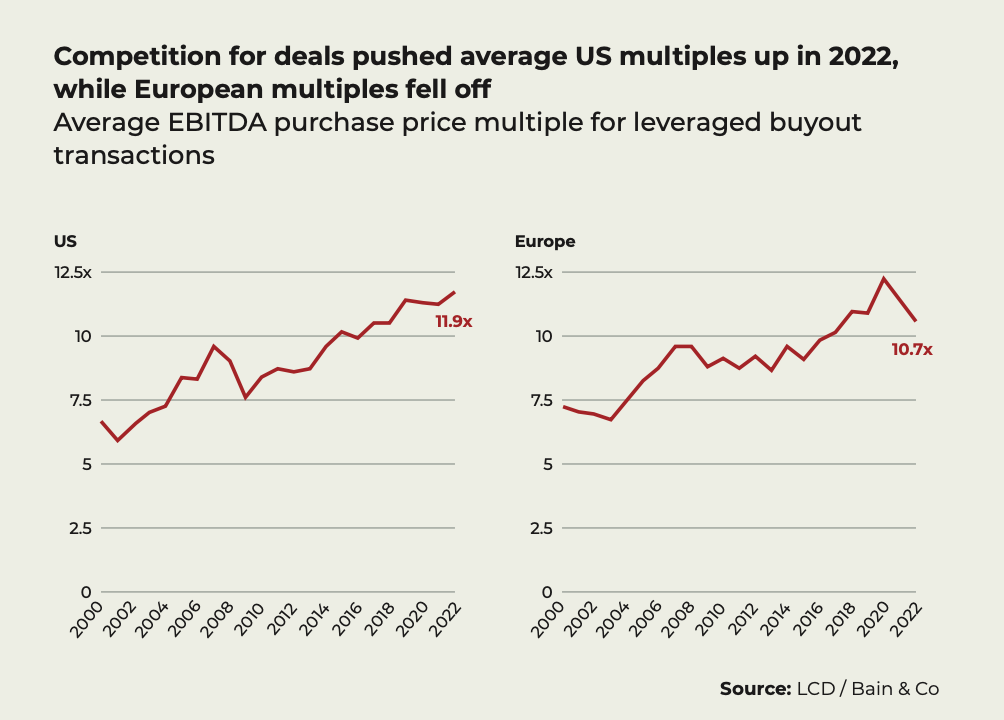

But some in the industry have warned that private equity is not immune from the effects of slowing economic growth, geopolitical uncertainty and a decline in dealmaking. Marc Rowan, chief executive of one of the biggest private equity groups, Apollo Global Management, warned in August that ‘this year has really marked the end of an era’ for private equity. In July the chief investment officer of Singapore’s sovereign fund GIC said ‘tailwinds’ such as cheap money had gone ‘and I don’t think they are coming back any time soon’.

Christian Wicklein, who has helped to lead the expansion of individual investment into private markets during 13 years as co-head of private wealth at Swiss-based private equity firm Partners Group, says the predictions of massive growth still make sense if you are not ‘distracted by the short-term macro picture’. ‘More fundamentally, when you look at the roles of public markets versus private markets, they have been swapping roles,’ he says. Rising numbers of companies are reluctant to list their shares on public markets, so it’s the private markets that are ‘financing the biggest part of the real economy’.

[See also: Spear’s 500 Index: Private Equity & UHNW Alternative Assets]

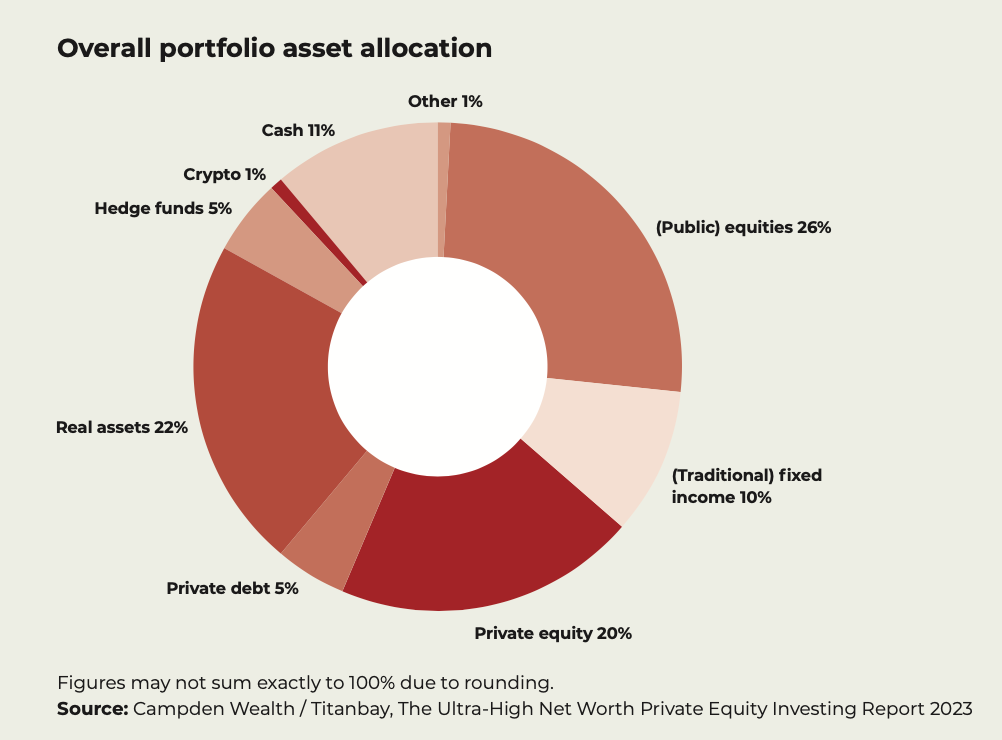

Just as importantly, while pensions funds, sovereign wealth funds and other institutions have long allocated a lot of their investments to private markets, when it comes to individual investors ‘we are barely scratching the surface’, Wicklein says. ‘Private investors account for around 50 per cent of global assets under management, but they only provide about 16 per cent of AuM in the alternatives sector. I’m not saying that imbalance will be fully corrected, but even if there’s only a bit of a catch-up you will see a very significant growth trajectory.

‘There are very strong structural tail-winds for the industry. The space has tripled about every 10 years – it’s now nearly $10 trillion and we believe it will go somewhere close to $30 trillion in 10-15 years.’

Making private markets more accessible

One of the biggest deterrents for small investors has historically been the requirement to lock up money for up to 10 years in typical closed-end fund models. However, Partners Group has been a leader in rolling out ‘evergreen’ or perpetual products, which allow limited withdrawals at intervals. Thirty per cent of Partners Group’s $142 billion in AuM is now in evergreen products. That growth has been conducted at a cautious pace to allow time to educate investors, Wicklein says, because the last thing any asset manager wants is ‘surprised or panicking investors’. ‘It’s absolutely priceless to have investors who really understand what they’re invested into, and you need to take the time to get that right and build portfolios in a diversified manner.’

Individual investors are estimated to hold an average of well under 5 per cent of their portfolio in private markets, compared to about 30 per cent for institutional investors and sovereign wealth funds. Sachin Khajuria, a former partner at Apollo Global Management, believes the next decade could see wealthier individuals placing 20-25 per cent of their portfolios in private markets. He has written an insider’s guide, Two and Twenty: How the Masters of Private Equity Always Win, and says investors can no longer rely on public markets to provide enough diversity to fund their retirement. Only about 15 per cent of companies with revenue over $100 million are publicly held, according to Bain & Co’s Global Private Equity Report 2023.

‘There needs to be further development of regulations, products and information, especially on the retail side, but there will be a rising market share of balance sheet going to private markets,’ Khajuria says.

Institutional investors will also rely more heavily on private markets because they offer an ever wider menu of investment options, he adds. ‘A big driver is the fact that private markets are offering much more than private equity or leveraged buyouts; in fact, the biggest growth areas are things like private credit. To think of private markets as just private equity is like equating a Motorola cell phone from the Nineties with the latest iPhone: it’s not even close.’

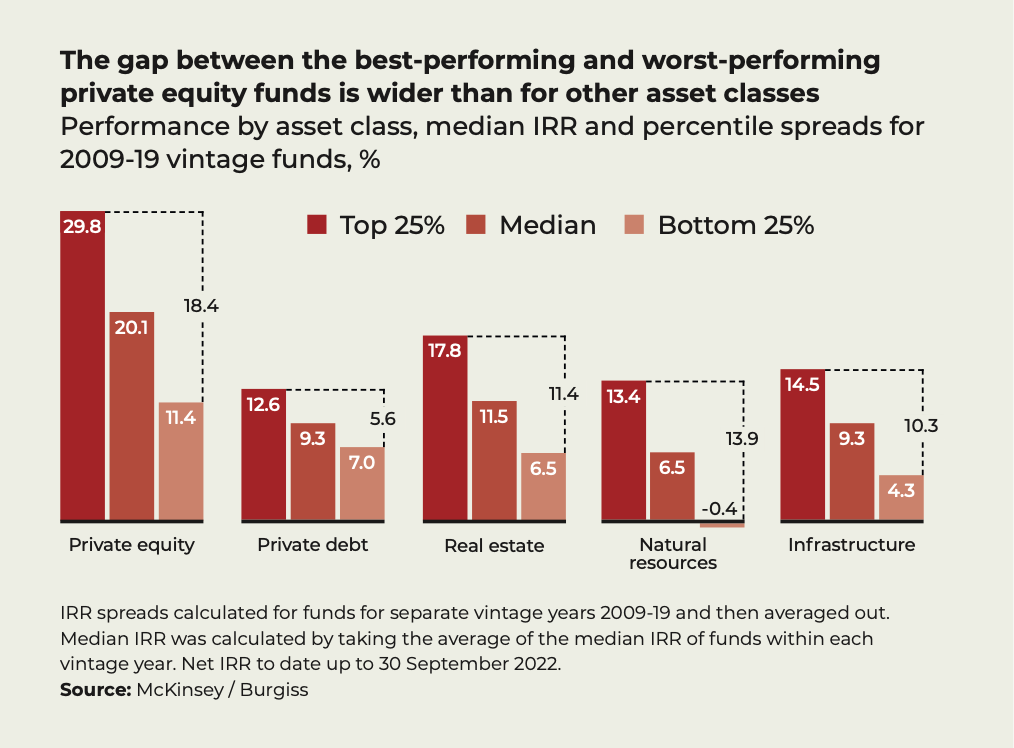

Education is key

Headwinds such as higher interest rates and falling market valuations mean there is likely to be a ‘thinning of the herd’ among private investment managers, Khajuria believes: ‘You’re going to have a greater dispersion between those who can consistently be accretive to their clients’ portfolios and those who struggle. And the trick, of course, is how to identify which is which. It’s not just size or brand name – you can’t just say “always buy KKR” or “always buy Blackstone”. You’ve got to look into each fund and its managers.’

That makes education crucial, Khajuria says, ‘because you could have the right idea, which is to diversify in the private markets, but simply buy the wrong one’.

Joan Solotar from Blackstone agrees on the importance of ensuring that investors and their advisers fully understand the intricacies of an investment world that has previously been restricted to sophisticated and well-resourced investors.

[See also: Spear’s 500 Index: UHNW Wealth Managers]

‘If you’re a financial adviser who’s never worked with anything other than products with daily liquidity, you have to take the time to be educated and understand how these fit in a portfolio, and how they can act in all different environments,’ she says. ‘So we spend a lot of time up front evaluating the firms that we want to partner with and have them distribute our products. So it’s not just that they’re doing due diligence on us and our fund, we are also doing due diligence on them.

‘We’ve created an educational programme we call Blackstone University to educate, not just on a particular product, but general education on private investing and structures. It really does require individual attention and in-person meetings, supplemented with online material.’

A lesson in liquidity

Under Solotar, Blackstone’s Private Wealth Solutions business has amassed more than $240 billion in AuM for individual investors since 2011 – an increasingly important chunk of the firm’s total portfolio of about $1 trillion. And she is confident the share of individuals’ portfolios that is invested in private markets will continue to grow.

‘Most chief investment officers of the major firms recommend anywhere from 10 to 25 per cent in private investments, and today the number for individuals sits at 5 per cent or below, depending on whose estimates you’re looking at,’ she says.

With most private investments requiring money to be locked away for considerable periods, Solotar says an important step forward for individual investors has been the development of ‘semi-liquid’ products, meaning ‘they will have either monthly, or quarterly, or semi-annual availability of liquidity’.

[See also: Advisers to the super-rich have a new model for success]

There was a powerful reminder in late 2022 of the difficulty individual investors can still have with limited liquidity, when Solotar’s firm was forced to limit withdrawals from its Blackstone Real Estate Investment Trust (BREIT). The $69 billion BREIT was set up to invest amounts as small as $2,500 for individuals, with withdrawals capped in order to avoid any rush that might force the managers to hold a fire sale of properties.

Solotar says the liquidity pressure at BREIT actually showed that the design worked as planned. ‘The head of an alternatives business within one of the big global firms said to me, “We wouldn’t have [ joined] your fund if you didn’t have the cap.” That was the whole point.’ But after the caps were triggered, Blackstone delayed the planned launch of a flagship private equities fund known as BXPE, which has been designed to allow wealthy individuals to invest in corporate buyouts and equity-oriented strategies such as late-stage venture investments and buying stakes in other private equity funds.

Lessening the burden with technology

Another promising development for broadening access to private investments has been the growth of fintechs and intermediaries which can ease the administrative burden for individuals and pool their investments into sums large enough to be handled by private investment houses. ‘There’s been a big improvement in technology, with companies like iCapital [founded in 2013] and Allfunds [launched in 2000], which have taken away some of the friction and operational burden,’ Solotar says.

[See also: Why this generation of billionaire tech barons is a danger to the planet]

German intermediary Moonfare says it has gained more than 50,000 investors since 2016 using an online system that allows new investors to navigate traditionally cumbersome ‘know your customer’, anti-laundering and other regulatory hurdles within 15 minutes.

Thomas Eskebæk, chief executive of the Dublin- and London-based platform Titanbay, says that by aggregating investments it cuts the administration burden on private investment houses ‘compared to if they had the same number of investors directly accessing the fund’.

New rules are needed

A serious headache for fund managers is the fact that national governments set different rules about which investors are allowed to invest in private markets, in some cases requiring a minimum of $5 million in investable funds, and in others requiring the investors to pass tests to show they understand investment rules.

‘Within Europe, the countries that offer more freedom to sophisticated and wealthy investors to select their own investments include the UK, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Denmark and Netherlands,’ Eskebæk says. ‘On the other hand, France, Spain and Portugal are the most restrictive jurisdictions, citing consumer protection as the reason.’

European regulators have revised the rules for instruments called European long-term investment funds (ELTIFs) to encourage a broader uptake of long-term private market investments, with Goldman Sachs Asset Management among the firms responding with new products. Goldman’s ‘Private Markets ELTIF 2023’ can accept investments as low as €10,000 from investors in the EU, to be mainly invested in non-listed company shares with a smaller allocation to private credit. It is the first in a series of similar products specifically designed for individual investors, according to Barry Fricke, the firm’s regional head of alternatives distribution for wealth.

[See also: ESG investments rise steeply among HNWs – although the ‘S’ lags behind]

Alongside the new ELTIF rules, significant improvements are under way in the operational ‘plumbing’ needed to support new fund formats and ‘open up private markets to individual investors’, Fricke says.

One of the most famous private equity firms, KKR – whose dramatic 1988 buyout of RJR Nabisco for $25 billion was immortalised in the book and TV movie Barbarians at the Gate – expects up to half of the capital it raises in the next few years to come from individual investors, according to Bain & Co.

A word of caution

Not everyone is so optimistic, however. Dan Schneider, co-founder of Brazil-based alternative asset manager SPX Capital, agrees there is huge potential for long-term growth in private markets but says the private equity outlook for the next few years is far from rosy because of high interest rates and sagging company valuations.

‘I’m really careful in selling this kind of product to retail investors, because even though they tell you that they understand the risks, and they’re ready for it, they’re often not,’ he says.

[See also: Family office investors favouring ‘passion assets’ in volatile times]

Alternative asset managers should be careful about what they wish for, Schneider warns, because the predicted flood of smaller and less sophisticated investors may lead to political and regulatory pressure to increase transparency and regulation to protect those new players.

Jeff Hooke, a former private equity executive turned finance lecturer at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins Carey Business School, says he expects alternative asset managers to use their lobbying clout to fend off full disclosure of what he says is an opaque, over-hyped sector plagued by excessive fees and a lack of transparency.

‘In terms of knowing what is really going on with fees, valuations and potential conflicts of interest, the clue is in the name: “private”,’ says Hooke, whose six books include The Myth of Private Equity. When the high fees charged by private equity managers are taken into account, only about 25 per cent of their funds actually outperform a low-fee balanced index fund of publicly listed companies, he says, and that is without adding a notional premium of perhaps 3 per cent that an investor might demand for having their money tied up for years.

Blaming what he calls the hype of a secretive industry with massive marketing dollars, Hooke says there is little proof that most leveraged buy-outs of companies lead to better performances at the targeted companies. ‘The whole business was built on a foundation of sand if you look at the real numbers, but nobody does that,’ he says. After taking off in the Eighties, the private equity sector ‘had a golden period of 10-12 years from the early Nineties when they had a good track record, but that is the only time they have really performed’.

[See also: HNW investors maintain appetite for alternatives amid market volatility]

Hooke believes private equity ‘will keep growing, partly by opening up a whole new market of people who aren’t so rich, ordinary people with 401(k) [retirement] plans’. An individual might be able to invest only $50,000 in private markets, ‘but if you multiply that by 10 million people it’s serious money’, says Hooke, who fears smaller investors will always come second to wealthier clients on issues such as fees and access to the most lucrative deals.

Recent attempts by several private equity firms to shore up their fundraising by offering significant fee discounts to large investors have already prompted warnings by some lawyers that there could be grounds for litigation by smaller investors who are still paying full fees.

Outcomes speak for themselves

Solotar is adamant that Blackstone’s funds do not preserve their ‘juicier deals’ for elite investors, and she rejects the claims of an unlevel playing field on fees. ‘I don’t think individuals are disadvantaged,’ she says. ‘There’s not a different fee chart for an individual versus an institution. There are discounted fees for bigger-scale investments, just like when you go shopping and they tell you a price is £4, but it’s £7 if you buy two.’

Such criticism of private equity and other private models ignore the fact that highly sophisticated investors have kept putting in their money and drawing solid cash returns, she says: ‘Does it make any sense that the smartest investors in the world and the biggest institutions in the world are allocating 25-50 per cent of their assets in these sectors, and yet they’re somehow being duped?

‘The proof is that they’re actually getting the cash back from their investments at the end of the day, so it’s very tangible. I don’t think it’s that mysterious.’

This story first appeared in issue 89 of Spear’s, available now. Click here to buy a copy and subscribe