When Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev is spotted, it is usually in salubrious surroundings over which he enjoys full control. Perhaps he’s gazing serenely out from his $300 million Monaco penthouse; reclining in his Airbus private jet; applauding in the royal box at AS Monaco, the football team in which he owns a majority share; or celebrating a victory in his $20 million racing yacht, Skorpios, which is named after the Greek island he also owns.

[See also: Introducing Spear’s Magazine: Issue 91]

But in January, the 57-year-old businessman, whose fortune is estimated at between $6 billion and $7 billion, found himself somewhere less glamorous. He was photographed walking into a Manhattan courtroom. He wore a modest dark navy suit, a coat draped like a cloak over his shoulders and an anxious look. After a nine-year legal battle, in which one development after another had gone against him, this seemed like a final chance to obtain what he considered to be justice.

In a courthouse just a stone’s throw away sat Donald Trump, who – along with his company – was being prosecuted for fraud by New York attorney general Letitia James, and who was ultimately ordered to pay a $354 million fine. Rybolovlev was also prosecuting an alleged fraud – one he claimed had been committed by Sotheby’s auction house, which he felt merited a similar amount in damages: $380 million.

[See also: Succession at the House of Arnault: who will wear the crown?]

The other main player in the legal saga was a Swiss art dealer named Yves Bouvier, a man Rybolovlev claimed had duped him out of $1.1 billion from the $2 billion sale of 38 works of art between 2003 and 2014. Bouvier consistently denied any wrongdoing, claiming he acted as a dealer, free to set his own profit margins, and not as Rybolovlev’s agent.

At midday on 11 January, Rybolovlev took to the stand. Eyes glistening, he told the court that his mistake was to trust someone he had considered a friend. ‘When a person is like a member of your family, there’s a point in time at which you begin to completely and utterly trust a person,’ he said.

The declaration raised eyebrows: could a billionaire, one presumably used to people trying to gain his confidence in order to extract some of his vast fortune, really have fallen for one of the oldest tricks in the book: the street hustler who promises to get his customer the very best price? And did any deception – if indeed it had taken place – amount to fraud?

The ascent of Dmitry Rybolovlev

Born in 1966 in the city of Perm near the Ural mountains, Dmitry Rybolovlev initially followed in the footsteps of his doctor parents before studying economics in Moscow. In 1994 he set up his own investment bank, Kredit FD, backed by businessmen from various large industrial concerns.

Rybolovlev’s ascent to wealth, amid the economic anarchy of Boris Yeltsin’s Russia, has all the classic ingredients of an oligarch’s rise: a swiftly accumulated fortune, useful political connections, the death of business associates, and the takeover of his business by Vladimir Putin’s allies.

[See also: Russian billionaires begin legal challenges against UK sanctions]

As Yeltsin sold off thousands of state-owned businesses following the ruinous Western prescription of ‘shock therapy’ capitalism, Rybolovlev bought one of the heavy industrial concerns of resource-rich Russia. He built up major stakes in two Urals potash firms: a majority stake in Uralkali and a fifth of the shares in Silvinit.

By 1995, Rybolovlev, then 29, was a multimillionaire who wore a bulletproof vest, employed bodyguards and was chauffeured around in an armoured car. That same year, he moved his family to Geneva, out of harm’s way. Months later he was arrested and imprisoned for allegedly arranging a hit on a business partner, who had been gunned down in his home. Rybolovlev, who said he was framed, spent 11 months behind bars before being released. He was indicted, but in 1997 was acquitted by the Perm Regional Court. The verdict was later confirmed by the Presidium of the Supreme Court, the highest court in the Russian Federation.

Now he experienced the other end of post-Soviet Russia: its brutal prison regime. At times he shared a cell with 60 other prisoners – ‘an entire summer in jail in burning heat’ with bunk beds three tiers high, he recalled to the journalist Arnaud Ramsay in the book Dmitry Rybolovlev: The Man behind Monaco’s Football Renaissance. The former aspiring doctor handed out medical advice to inmates and understood there were no ‘guarantees in prison’, whatever his status on the outside might have been. ‘It’s vital to adapt,’ he added. ‘I thought of it as an experience.’

[See also: Kyiv: a dystopian reality where any criticism of Ukraine’s leadership is silenced]

He survived the Russian prison system by developing super-human levels of determination and self-belief. Dmitry Chechkin, the businessman’s spokesperson, later credited Rybolovlev’s willpower, explaining how he rejected an offer of freedom in exchange for the sale of his company Uralkali: ‘Rybolovlev is impervious to pressure; it is one of his strongest character traits.’

Out of jail, Rybolovlev joined his family in Geneva and continued to build his empire. He formed an alliance with Belaruskali, the state-owned potash company of neighbouring Belarus, and by 2006 his companies supplied 40 per cent of the global potash export market. In 2007 he listed 12.5 per cent of Uralkali on the London Stock Exchange, instantly becoming a billionaire and one of the 100 richest people on the planet. His company’s share price rose 300 per cent in the next eight months. In the same period, he set up a network of offshore companies and trusts in the tax haven of Cyprus, bought 10 per cent of the Bank of Cyprus, and, in 2012, acquired a Cypriot passport.

Rybolovlev left a void in Russia. Literally. In 2006, in the town of Berezniki, under which ran the deep tunnels of one of Rybolovlev’s potash mines, a vast sinkhole opened up. The town had seen sinkholes before and has seen more since, but this one was bigger than a football pitch at 170 metres by 90 metres. It swallowed up buildings and threatened to force the relocation of much of the town. In 2008, Putin’s deputy Igor Sechin, who was leading a widespread crackdown on oligarchs at the time, launched an inquiry into Berezniki’s sinkholes; Uralkali paid $250 million in compensation.

[See also: Two years on from Russia’s invasion, the fog of war has thickened in Ukraine]

The political pressure on Rybolovlev grew as the soaring value of Uralkali attracted the interest of the Russian state. In 2010, three businessmen with Kremlin ties, financed with a $3 billion loan from the Russian state-owned bank VTB (which has been under sanctions since 2014), expressed an interest in taking over his company.

But Rybolovlev’s luck held. He faced no further consequences for the disaster in Berezniki and, what’s more, managed to obtain a premium price for a 53 per cent majority stake in his business empire – reportedly between $5 billion and $7 billion in cash. Now all he had to do was decide how to spend it.

The oligarch playbook

Fast forward to 17 May 2017 and the deciding game of Ligue 1, France’s top football league. In the royal box at Monaco’s Stade Louis II, two very wealthy men follow their team’s fortunes, wincing as Saint-Étienne’s goalkeeper saves a fine shot from within the penalty area by Kylian Mbappé, grimacing when Radamel Falcao’s volley is deflected, but elated when the former manages to put the ball into the back of the net, and as Valère Germain adds a second with the last kick of the game. As the full-time whistle is blown, Rybolovlev embraces his friend, Prince Albert II of Monaco, and the crowd roars in celebration.

Winning the championship – Monaco’s first in 17 years – simply could not have happened without the bulging wallet of Rybolovlev. After buying the club for a single euro in 2011 and moving to Monaco from Geneva, he invested €300 million in top-class players. Since then, he had continued to follow the customary oligarchic playbook. He entertained celebrities (guests in his box at AS Monaco included Novak Djokovic, Lewis Hamilton and Bono); invested in a 110-metre yacht and a private jet (an Airbus A319CJ); and snapped up an international property portfolio spanning Paris, Saint-Tropez, Gstaad and Hawaii. His Manhattan penthouse cost $88 million (thought to be the most expensive New York transaction at the time in 2011), and his $300 million Monaco penthouse was believed to be the priciest in the principality.

[See also: UK ‘discriminating against rich Russians’, says international lawyer]

But, for a time, Rybolovlev was dogged by scrutiny. His 2008 purchase of Trump’s Florida mansion for $95 million – more than twice what the future president had paid – drew attention from reporters. But the Florida property was later carved up into three lots and sold for a little more than Rybolovlev paid for it, which undermined any suspicion the deal was a favour for Trump.

Also in 2008, Rybolovlev’s wife, Elena, filed for divorce, alleging infidelity. She wanted half his fortune: $3.5 billion. But in 2015 a Swiss court whittled that down to only $604 million.

In 2016, French investigative website Mediapart alleged that Rybolovlev was involved in third-party ownership of footballers, a practice that was banned by FIFA the previous year. But AS Monaco claimed at the time that ‘the club had always complied with French and international regulations concerning player transfers’. A spokesperson for Rybolovlev said: ‘Investments in football were made for as long as international regulations allowed it. As soon as the law changed [on 30 April 2015], no new investments were made.’

In 2018, Der Spiegel published a report claiming Rybolovlev was managing the foreign assets of Putin associate Yury Trutnev. As natural resources minister, it was Trutnev who led the government commission that exonerated Rybolovlev of culpability for the disaster in Berezniki. But a spokesperson for Rybolovlev says he and Trutnev ‘have never been involved in any joint businesses, financial projects or investments’. So, still, Rybolovlev remained unscathed. Until, that is, he set foot in the art world.

Into the art world

Rybolovlev’s foray into this new arena was facilitated by Tania Rappo, the Bulgarian-born, Russian-speaking socialite wife of his Swiss dentist. It was Rappo who introduced him to Yves Bouvier, an art handler who rented out thousands of square feet of lockers to collectors at the Geneva Freeport, a storage centre that could be used to enable owners of artworks to avoid certain taxes. He was also an art dealer who liked to operate below the radar.

I met Bouvier in 2018 while writing my book The Last Leonardo, about Salvator Mundi, one of the many paintings he sold to Rybolovlev. In a scruffy fleece and bleached jeans, he couldn’t have looked less like a blue-chip art dealer. Bouvier and the Russian fledgling collector bonded over a Chagall, which Rappo had sourced and which Bouvier showed to Rybolovlev at the freeport. Rybolovlev asked Bouvier to help him build a small collection of world-class masterpieces.

[See also: UK art market falls behind China amid global dip in sales]

‘Dmitry thinks he’s superior to everyone,’ Bouvier later recalled in our 2018 interview. ‘That means, if you discuss real estate, he’s superior to you. You talk about medicine, he’s superior to you. You’re discussing art with him, he thinks he’s superior to you. You discuss any subject at all, he thinks he’s more intelligent than the rest of the world.’ That attitude would not stand the Russian in good stead when he entered the art market – a commercial and legal environment he knew nothing about.

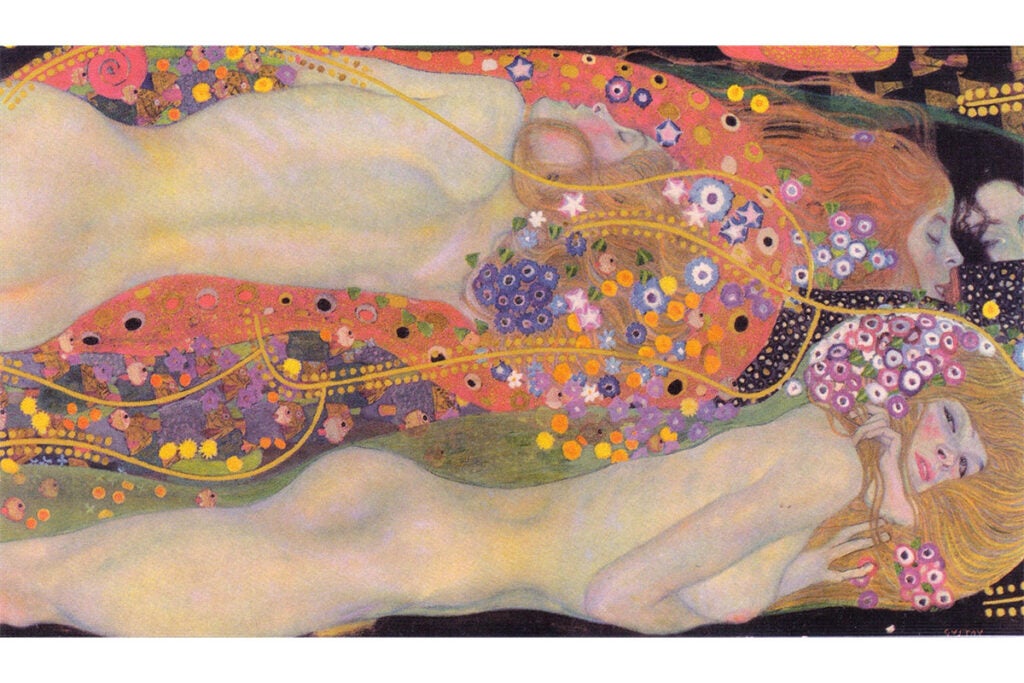

Bouvier located works for Rybolovlev by the most famous names of Modernism, and the odd Old Master: Modigliani, Monet, Matisse and Magritte – and that was only the ‘M’s. There were also pieces by Picasso, Klimt and Leonardo da Vinci, so there was no doubting the quality. The way Bouvier operated, however, would later be the subject of Rybolovlev’s displeasure.

‘It’s not moral, but it’s legal’

Here’s what he did. Bouvier would agree a verbal deal with Rybolovlev that he was to source works of art, charging Rybolovlev a 2 per cent commission. Bouvier advised Rybolovlev to keep his collecting activity secret, arguing that the prices are driven up if sellers know how rich the buyer is. Sellers, too, had reasons to hide their identity – it could be seen as a sign that they were in financial difficulty.

[See also: Investing in art remains a risk worth taking]

Bouvier would establish the seller’s price and then quote Rybolovlev a ballpark figure, tens of millions of dollars higher than the seller’s price. If Rybolovlev expressed an interest, Bouvier then agreed to buy the work from the seller through his own company.

At the same time, he sent Rybolovlev emails in real time claiming that he was negotiating with the sellers to get the best possible deal. ‘The owner is quite prepared to sell… I think I could get him to accept €20 but I want to try lower with a fast payment,’ Bouvier emailed about a Toulouse-Lautrec, omitting the obvious millions in the number. ‘They’re holding

back for 180 and are at the breaking point. I think they are ready at 190. But I should be able to twist them to reach 185 [sic],’ he wrote of a Klimt in another email to Rybolovlev’s office.

So Bouvier bought Salvator Mundi one day in 2013 for $83 million and sold it to his Russian client the next day for $127.5 million. He bought a Klimt for $120 million and flipped it to Rybolovlev for $183 million. ‘It was just sales patter,’ Bouvier said of his emails when I met him. ‘It’s not moral, but it’s legal.’

[See also: Outstanding art advisers for high-net-worth collectors]

Having bought the work, Bouvier then sent Rybolovlev contracts, overseen at Rybolovlev’s request by Swiss law firm Lenz & Staehelin. Invoices came later, naming one of Bouvier’s offshore companies – a different one each time at first – as the seller of the work to Rybolovlev’s art-holding offshore companies Xitrans Finance and, later, Accent Delight International, both registered in the British Virgin Islands.

Rybolovlev and his team were initially not aware that the seller’s companies were in fact owned by Bouvier. When Bouvier started using the same company, MEI Invest, to sell artworks for a second time in 2006, Rybolovlev’s office accepted Bouvier’s explanation that it was a way to ‘screen’ their identity. After Rybolovlev had purchased a piece of art, he paid Bouvier the two per cent commission as verbally agreed, which Bouvier’s representatives say related to ‘the guarantee, transportation and storage services’.

Suspicions of foul play

This may sound like an odd arrangement. But not in the art market. ‘In some cases, buyers have been known to give their agents the funds to purchase artworks in the agent’s name in order to conceal the actual buyer’s identity, though I don’t advise it,’ US art adviser Todd Levin told me. ‘Rybolovlev is certainly not the first collector to engage in this practice.’ (Bouvier denies that he acted as an adviser to Rybolovlev and was instead a dealer.)

‘I’ve never signed a contract when I have worked as an agent,’ said James Butterwick, who specialises in European and Ukrainian art. ‘You do it on a handshake and the basis of your relationship with that individual.’

[See also: The generational divide shaping the global art market]

Over the next 10 years, Dmitry Rybolovlev bought 37 works of art through Bouvier for a total of around $2 billion. In this entire period, Bouvier was the only contact Rybolovlev would use for his purchases. In court, Mikhail Sazonov, who had worked as a chief financial officer for Rybolovlev, was asked why. ‘Well, whenever the question came up, Mr Bouvier would say that every art agent is a crook, swindler and, basically, [in] the whole world [there] was only one trustworthy and honest person, and that is himself.’

Rybolovlev began to suspect foul play in September 2013 after reading an article in an Austrian newspaper which claimed the $183.8 million Klimt that Rybolovlev had bought through Bouvier had actually been sold for $120 million. Bouvier claimed the article was inaccurate and offered to obtain a valuation from Sotheby’s for the work, which would confirm he paid a fair price. A month later he did indeed forward to his Russian client a Sotheby’s valuation for the work at $180 million. But Rybolovlev was now suspicious, and he began to ask for valuations from Bouvier for other works he had bought.

Further evidence of Bouvier’s modus operandi came during a conversation with top art adviser Sandy Heller at a 2014 New Year’s Eve luncheon in St Barts. Heller told Rybolovlev that he knew the original price that Bouvier had paid for one of Rybolovlev’s works, because his client, billionaire hedge fund manager Steve Cohen, had sold it to him.

On the witness stand in New York, Rybolovlev later said that when he discovered the gulf between the price and what he had paid Bouvier, he was left ‘in a state of shock’. ‘My friend actually told me that he thought I was having a heart attack because I turned completely pale. Because really quickly, I understood, I comprehended that this has to do not with one painting. And the volume of transactions that was channelled through Yves Bouvier basically attested to the fact that the damages were astronomical. So I left the table after that.’

Laying a trap

Dmitry Rybolovlev wanted his money back – and began to strategise. He asked Bouvier to sell some of the works he’d bought from him for the same price he’d paid – after all, the valuations were in the ballpark. Bouvier declined. The oligarch invited his agent-dealer to meet him in Monaco, ostensibly to discuss his last payment for a Rothko. But he was laying a trap.

A few days before Bouvier was due to arrive, Rybolovlev invited Rappo to dinner at his apartment. He suspected that the dentist’s wife was in cahoots with Bouvier (it later transpired she had a 5 per cent cut on the sales and had made $100 million from the deals). Also present was the oligarch’s lawyer, Tetiana Bersheda, the 31-year-old, Russian-speaking daughter of a former Ukrainian ambassador to Switzerland who worked for the Geneva firm Canonica Valticos & Associés SA. Bersheda made a secret voice recording as Rappo discussed an outstanding payment due to Bouvier for Rybolovlev for a Rothko. The next day, the lawyer made a copy of her phone recording and handed it in to the police.

Bersheda was also using her phone to share information about Bouvier with Monaco’s law enforcement authorities. When I spoke to her in London in March this year, she told me this was normal for a lawyer representing a client whose complaint about an individual was being investigated. On 24 February 2015, she messaged Monaco’s Chief Superintendent Christophe Haget: ‘Good evening, he’ll be coming on the morning of the 25th. That’s for sure. We should stick to plan A. Please call me back when you can. Thanks for your time! Tetiana.’ The next morning, he replied: ‘Very well, I’ll call you back.’

On 25 February 2015, as Bouvier approached Rybolovlev’s apartment block, 12 police officers swooped in, handcuffed the art dealer and bundled him into a squad car. Bouvier and Rappo were taken in for questioning. Bouvier was told he was under investigation for fraud and money laundering and released on $4 million bail.

Yves Bouvier has his own explanations for why Rybolovlev had turned on him and demanded valuations and the resale of some of his pictures. In 2017, he said: ‘Rybolovlev’s attacks against me had nothing to do with the sale of art … Firstly, he was half-way through the most expensive divorce in history and wanted to depreciate the value of his art collection. Secondly, he wanted to punish me for having refused to corrupt Swiss judges for his very expensive divorce. Thirdly, he wanted to steal my freeport business in Singapore and build his own for the Russian Federation in Vladivostok.’

Going global

At any rate, what had once seemed like a friendship quickly descended into a feud. Rybolovlev initiated legal proceedings against Bouvier in Switzerland, Singapore, the United States, Monaco and Hong Kong. Although no final figure is available, it is widely thought to have been the most expensive legal battle in the history of art.

Bouvier racked up a bill of CHF 6 million in three years on a team from intelligence and advisory firm Alp Services, according to Swiss magazine Le Temps. The bill for just one meeting (with 25 advisers) in January 2016 cost him almost CHF 1 million, according to the investigative Swiss website Heidi. (Bouvier sold his freeport businesses in Geneva and Singapore for knock-down prices.) Even these astronomical costs are likely to have been a fraction of Rybolovlev’s spend, but things did not play out as the Russian had hoped either.

[See also: Advisers to the super-rich have a new model for success]

It is illegal in Monaco to record someone’s conversation without permission, and the penal code specifies a penalty of up to €45,000 and a year in prison if the material recorded is ‘private or confidential.’ So, following the sting and voice recording episode, Rappo filed a complaint against Bersheda and Rybolovlev for breaching her privacy rights. ‘M. Bouvier had a very smart defence team,’ Bersheda told me.

Rybolovlev now found himself investigated for corruption and influence peddling. The media called it ‘Monacogate’. The Rock’s minister of justice Philippe Narmino resigned. The case is still open, and thus Bersheda and Rybolovlev are presumed innocent.

But the furore put the Bouvier-Rybolovlev affair in a new context, which reflected the concerns of the French judicial authorities, as well as of similar European and American authorities about the influence Russian money was buying in the West.

The mood had changed. Eventually, prosecutors in Monaco dropped their fraud investigation into Bouvier. Monaco’s High Court confirmed a judgment by the Court of Appeals, on the grounds that the investigation was ‘partial and disloyal’ against Bouvier. In Singapore the court decided that Rybolovlev’s offshore art-holding companies had ‘received what they bargained for and at the price they were willing to pay’. The Swiss prosecutor closed the case against Bouvier in December 2023 on the grounds of insufficient evidence. Following this Rybolovlev and Bouvier reached a confidential out-of-court settlement. Rybolovlev’s attorneys said: ‘The parties have reached a confidential settlement concerning all their disputes that involved proceedings in various jurisdictions. They have no claims against each other and will refrain from commenting on their past disputes.’

But that is not to say the state prosecutors were completely uninterested in Bouvier’s activities. They abandoned their pursuit of him for alleged fraud against and oligarch, but they did investigate him for tax evasion against the state. The Swiss authorities calculated that he could owe them €256 million in unpaid taxes. Last year, Bouvier paid up, though the sum was never made public.

In November 2023, Rappo and Bouvier’s complaint against Rybolovlev and Monaco’s state prosecutor was dismissed.

Rybolovlev v Sotheby’s

But Dmitry Rybolovlev still had one legal card left to play. He had learned that some of the pieces he’d bought from Bouvier had come via Sotheby’s private sales business.

In addition, Sotheby’s sometimes sent Bouvier valuations for works that Rybolovlev was either about to buy or had already bought – valuations which Bouvier forwarded to Rybolovlev in order to demonstrate to his Russian client that he was paying a fair price. To Rybolovlev, it looked like the auction house was hand-in-glove with the art dealer.

Bouvier’s contact at Sotheby’s, Sam Valette, was, it turned out, also Sotheby’s special client manager for Rybolovlev. It was Valette who sent Bouvier the valuations, and it was found that he had revised them upwards on a few occasions on Bouvier’s request, raising them by the odd $10 million or $20 million to figures close to what Rybolovlev paid for the work.

[See also: Recommended art lawyers for HNWs]

In 2018, Rybolovlev filed a $380 million lawsuit for damages against Sotheby’s in New York, accusing it of aiding and abetting Bouvier in his fraud. Sotheby’s denied the accusation, saying its representatives did not know who Bouvier was selling to.

The month after Bouvier and Rybolovlev agreed on the settlement in Switzerland, the Sotheby’s case went to trial. Rybolovlev’s US legal team, led by Daniel J Kornstein from Emery Celli Brinckerhoff Abady Ward & Maazel, tried to paint a picture of the close relationship between Valette and Bouvier. They noted that Valette sometimes sent Bouvier emails in French addressing him informally as ‘tu’, suggesting friendship, and on other occasions used the formal ‘vous’. This, prosecutors claimed, illustrated that Valette knew some emails were destined to be seen by others.

The lawyers also asked why Bouvier allowed Valette to become so close to Rybolovlev, unless he knew the auction specialist wouldn’t steal his client? On top of that, even though he was Sotheby’s client manager for Rybolovlev, Valette never once offered the Russian an artwork himself. Why would he do that, unless he knew that Rybolovlev was Bouvier’s man?

Yet, as the trial progressed, Kornstein’s horse fell at every hurdle. Sure, Sotheby’s sent valuations to Bouvier on request, but defence lawyers argued that the auction house had no idea if Bouvier was showing them to anyone. The ‘vous’ and ‘tu’? The two different kinds of emails could be accounted for by the fact that Valette had both a personal and business relationship with the Swiss dealer. The suggestion that Sotheby’s was in cahoots with Bouvier to overcharge Rybolovlev? Rybolovlev paid elevated prices on 23 deals in which Sotheby’s was not involved. The bumped-up valuations? Valuation of art is hardly an exact science. Different experts give different estimates. Prices can vary from year to year. They were just ‘round’ figures, a confident Valette assured on the stand.

By the time of the trial, Rybolovlev, his taste for art now soured by his experiences, had sold some of his Bouvier works at auction. Several had gone for much less than he paid for them, but one, Salvator Mundi, fetched $450 million – three times what he had paid. Bought by the ruler of Saudi Arabia, it became the most expensive ever sold. That good fortune was bad for Rybolovlev’s case against Sotheby’s. It was evidence that Sotheby’s could just as easily underprice a work of art as overvalue it.

After a three-week trial and only five hours of deliberation, the court acquitted Sotheby’s of all charges, though it did not force Rybolovlev to pay its costs.

Shining a light on the art market

‘The market has seen how problems can arise even when dealing with trusted blue-chip galleries,’ says art lawyer Judd Grossman of the impact of the case. ‘And savvy collectors have become more aware that the lack of a clear contract memorialising the parties’ understandings can give rise to disputes even among the most sophisticated parties.’

In other words, if there had been a signed contract between Rybolovlev and Bouvier stipulating the terms and conditions of his role as an agent, the billionaire would have had a much more compelling case. With a contract in place, Bouvier might have also been happy to be bound by its terms.

[See also: How the anti-money laundering reform might affect art dealers]

Others – including Rybolovlev’s legal team – argue it has highlighted the need for change. ‘This case achieved our goal of shining a light on the lack of transparency that plagues the art market,’ said Kornstein, adding that the verdict ‘only highlights the need for reforms, which must be made outside the courtroom’.

Certain industry figures say they would welcome increased transparency. Spear’s Top Recommended art adviser Julia Bell, of Parapluie, says she would have no problem with ‘a public register of title of ownership of a work of art; provenance would then be transparent in the sale transaction – it is no different from owning a car or property’.

But the number of prosecutions and art-related convictions is already on the rise, with the 2022 prosecution of fraudulent dealers Inigo Philbrick and his partner Robert Newland among the best known. The law is catching up, too. In 2020, the EU applied its anti-money-laundering directive to the art market; the US did much the same with the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020.

‘There’s more paperwork, more documentation relating to clear title, debt on an artwork and provenance,’ says Anthony Meier, a postwar secondary market dealer and president of the Art Dealers Association of America. ‘It’s about aggregate momentum,’ adds Meier. ‘Bouvier-Rybolovlev is one of the factors. Ten small stories add up to one large one.’

In that sense, Dmitry Rybolovlev may have done the art world a favour – albeit at vast personal expense.

Yves Bouvier was contacted ahead of publication of this article but did not respond. After publication, Bouvier’s representatives contacted Spear’s. This article has been updated to reflect the fact that Yves Bouvier denies that he acted as an adviser to Dmitry Rybolovlev and was instead only a dealer or a seller; to note that the commission he charged Rybolovlev was related to ‘the guarantee, transportation and storage services that he provided’; to include Bouvier’s explanation for Rybolovlev’s decision to initiate legal proceedings against him; to include further context for the reasons investigations into Bouvier were dropped; and to correct the percentage fee charged by Tania Rappo, which was 5 per cent, not 10 percent.

This feature was first published in Spear’s Magazine: Issue 91. Click here to subscribe