Back in October 2011, the bishop of London was a worried man. He had good reason. Hundreds of Occupy London protesters living in 200 tents were encamped outside the west door of St Paul’s Cathedral – and were refusing to go away. They had been there a fortnight already. Their presence – and the tensions between them and the police – had led the cathedral authorities to close St Paul’s doors for a week – something that had never happened before.

One of the cathedral’s canons, Giles Fraser, had resigned after asking the police to leave and allow the protesters to express their right to demonstrate in peace. By late October the cathedral was taking legal action, along with the Corporation of London, to have the protesters evicted, amid fears of the bloodletting that might follow.

[See also: Introducing Spear’s Magazine: Issue 89 ]

Looking for answers, the bishop, Richard Chartres, picked up the phone and dialled the number of – of all people – an investment banker. The banker’s name was Ken Costa. At the time he was the chairman of Lazard, a US-listed international bank that had $150 billion in assets under management. Chartres told him about the situation at St Paul’s and appealed for his help. Would Costa go in there and mediate? Would he talk to the people, try to understand what they were feeling, and speak to the City fathers, too? The threat of violence was palpable.

Costa, who had 35 years in investment banking to his name – not least at UBS, where he had been chairman of its EMEA division – didn’t blink. Still dressed in his banker’s suit and tie, he walked out into the hostile crowd, determined to listen.

When he speaks with me in a sitting room at his double-fronted house in a quiet street near Holland Park, Costa, 73, is dressed casually in jeans, a pristine white shirt and a blue Patagonia gilet. His speech is measured, serious – as befits a man who has spent nearly 50 years advising some of the world’s richest families, from the Oppenheimers to the Barclay brothers – and his accent carries a gentle chime of his South African upbringing. He has invited Spear’s to his home to talk about The 100 Trillion Dollar Wealth Transfer, his new book, which bears the mark of those moments more than a dozen years ago when he ventured into the crowds on the steps of St Paul’s. He’s still haunted by that time, and in particular the intensity of the outrage he witnessed. Above all, Costa says one question on the lips and placards of the protesters back in 2011 stays with him: ‘If capitalism is so good for you, why isn’t it good for me?’

‘Capitalism is in a crisis that could turn into a catastrophe’

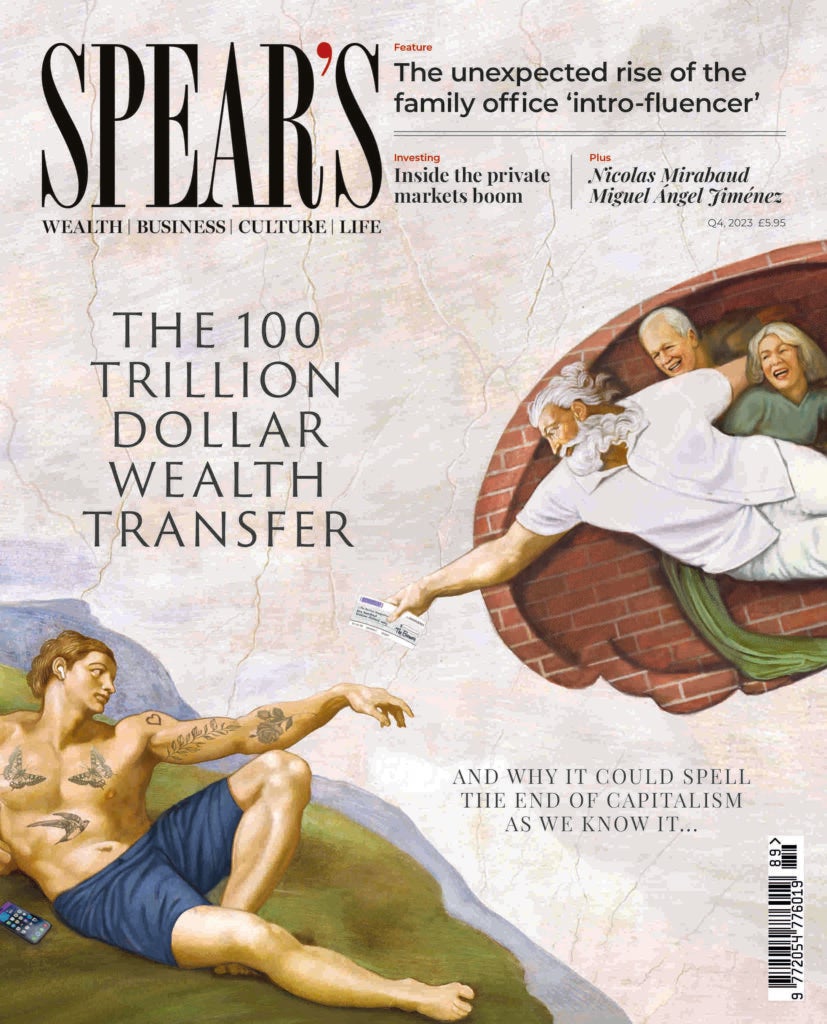

In the book Costa explains that, today, capitalism is in a crisis that has the potential to turn into a catastrophe. Over the next decade, in the US alone, $61 trillion in assets will be passed from the post-war Boomer generation to Millennials and Generation Z, those born between around 1980 and 1995, and 1995 and 2010 respectively. (In Britain the figure is put at £5.5 trillion.)

‘This is the Great Wealth Transfer of our age,’ he writes. ‘And how we deal with this legacy will change the way we live now and reshape the global economy.’ In different circumstances this might not be a great cause of worry. But in 2023, it is. Costa’s central thesis is that the young – shut out from the wealth enjoyed by the elder generations for so long – are bitter. More than this, they blame the Boomers for trashing the planet in a headlong rush for short-term riches. The Boomers, meanwhile, are guilty as charged – and they’ve made matters worse by being arrogant and resistant to change.

[See also: While billionaire numbers drop, generous donors give more ]

As a result, the youth of today have a renewed enthusiasm for ‘big state’, ‘state-controlled’, collectivist models, what Costa calls ‘New Socialism’. Bagging Millennials and Generation Z together as ‘Zennials’, Costa gives a stark warning, which is both the core of the book and his reason for writing it.

‘Avoiding the destruction of the incentive-based market economy is the primary aim, for capitalism is the one system that is flexible enough to respond effectively to the changes that necessarily need to be made,’ he writes. But it’s deeper than this. ‘It is incumbent on the Boomer generation to persuade the Zennials that liberty is at stake.’ The problem is relations between the old and young are so poor that it may not happen. ‘It is a possibility that intergenerational tensions reach an irreversible tipping point and the entire economic project could collapse.’

Faith in the process

So in other words, the kids are getting their hands on the farm just as they are becoming angry and disillusioned enough to tear it down. ‘The older generations are scared to hand on the earth to those they feel are not worthy of it,’ warns Costa, ‘while the emerging generation feel they are being handed a ruined creation.’ And that’s why – rather like the tents versus the City in 2011 – Costa has decided to walk into the fight and stick his head above the parapet. This time he hasn’t received a summons from the Bishop of London, but it’s clear his faith may play a part. The walls of the sitting room where our conversation takes place are lined with religious texts and theological commentaries – Thomas Aquinas rubs shoulders with the letters of CS Lewis and a two-volume biography of Bishop John Colenso, an Anglican theologian and scholar of the Zulu language. There is a photograph of Costa with the Pope.

The banker, a committed Christian, preaches at a church in Hammersmith and tells me he considered a career in the church. He found God when he was at Cambridge in the Seventies – around the same time as he formed his friendship with the current Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, who was a contemporary.

‘Faith came alive in Cambridge,’ Costa declares, before explaining that he came to the conclusion that faith was non-rational, but not irrational. ‘Once you’ve accepted that [existence] is a journey of faith, the consequences affecting the way you live, your whole understanding of material possessions, philanthropy and all of that undergirds everything.’

Instead of becoming a priest, Costa went into finance. In 1976 he joined SG Warburg, where his first boss was the banking icon Sir Siegmund Warburg. His advice, something that has ‘affected all the wealth management and any advice with clients I’ve ever done, is first make your person your friend, then become their banker’, says Costa. ‘There’s that personal relationship that actually made me convinced that this was helping people understand the issues, the complexity of the world around them. [That] was something that I wanted to aspire to, and I happen to be gifted at.’ So is there a pastoral dimension to banking? ‘Oh, sure.’

As well as his faith, Costa’s life and worldview has been shaped by Nelson Mandela, a personal hero. (A photograph of the two of them together is beside him.) Growing up in Apartheid-era South Africa in the late Sixties – when Mandela was imprisoned on Robben Island – Costa was president of the student council at the all-white University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg and a member of the National Union of South African Students, which campaigned against educational segregation. A friend at the time was another student leader named Steve Biko, who would subsequently die in police custody and become the focus of worldwide opposition to the South African regime.

‘You know that awkward situation where you meet somebody who is so iconic, and you sort of mumble your words… you don’t quite know what to say?’ Costa says, recounting a meeting with Mandela when he became a trustee of the former president’s children’s charity. ‘I sort of said to Madiba, which was his Xhosa [clan] name, “What advice would you give me?” I mean, it was just such a stupid kind of question. And I remember him looking at me and just saying, “Ken, you must make for peace. It is very easy to make for disagreement. You, Ken, must make for peace.”’ Costa delivers this with the laden cadences familiar to anyone who has met Mandela or heard a recording of him speak. ‘It’s a simplistic statement,’ he confesses, ‘but it’s riveted in my mind, and is one of those formative experiences.’ He looks over at me, and restates it with conviction. ‘It’s easy to make for disagreement, particularly when social media is raging, it’s easy to go into these silos. Can we make for peace?’

The new version of capitalism

To answer that question, capitalism has to change. He is certain that the days of ‘me first’, ‘greed is good’ capitalism epitomised by Wall Street’s Gordon Gekko (and presumably, once, by Costa himself since he rose to the top of investment banking during the Eighties and Nineties) are over. ‘Their culture has had its day,’ he writes in his book. It’s a striking statement from a stalwart of capitalism, who has been a financial supporter of the Conservative Party for 21 years and counts chancellor Jeremy Hunt among his friends.

More than this, at the heart of the intergenerational tension is the question of intention: what is the wealth being created for, and why should it be generated? ‘Doing well and doing good are co-equal considerations in the Zennials’ new vision of capitalism,’ Costa explains. ‘We used to say, “Run a profitable business and make it purposeful.” Today, it’s, “Run a purposeful business and make a profit.”’

While this is not a new idea – anyone familiar with business and leadership topics will have heard about purposeful capitalism before – it is still not the prevailing way of doing business, notwithstanding pages and pages of corporate reports given over to ESG. If it were, why would 56 per cent of 34,000 people polled across 28 countries have agreed with the statement in a 2020 survey that ‘capitalism does more harm than good in the world’?

But the dial will shift further as Millennials come to dominate the corporate landscape and move up the chain of command. But there’s an imperative for business to move with the times. ‘Zennials need to be given not just a reason to participate in society but a reason to want to,’ warns Costa. Do this, he believes, and they ‘can be galvanised to use the capital they will inherit in new and exciting ways’.

Purpose before profit?

As a result, the firms of the FTSE 100 and S&P 500 are going to be behaving differently 10 years from now, he predicts, putting purpose before or equally with profit. ‘That’s the edge that people are not seeing, because you’re dismissing them,’ Costa explains. ‘That next generation, it’s got capital, it’s got influence, it’s got technology, and it’s got power at its fingertips. And it has a very clear agenda.’

Part of that agenda is driven by Zennials feeling ‘personally responsible for the future of humanity’, says the banker, who notes a rejection of the radical individualism of the past decades. He observes in the young ‘the expansion of the self to encompass both you and the other’. ‘We rather than me…’ he writes, ‘the expansion of moral responsibility to suffer with the refugee and their hurting, regardless of distance. The collective moral standards of the Zennials are incredibly high.’

[See also: Revving up in style: Concours on London’s Savile Row returns for 2023 ]

If values are changing, so is value itself. Take crypto, which Costa likens to ‘a protest movement… a movement of a generation saying that “the way you [boomers] used to do things”, the ancient regime if you will, is crumbling and that a new story is establishing itself’. Costa points to a 2021 survey, which showed that 94 per cent of crypto investors were either millennial or Gen Z. With these investments generating value in something that the old don’t just disapprove of, but also don’t understand, Costa says crypto isn’t just an asset class, it’s also the expression of a generation, like free love in the Sixties.

But it’s also volatile. Once the young have got their hands on the $100 trillion they’re due to inherit, there is a very real possibility that billions of the world’s wealth could go up in smoke in the blink of an eye. Costa, who is not unsympathetic to crypto, calls for greater regulation of digital assets and warns Zennials to be careful. ‘Zennials would do well to perhaps take on some of that [Boomer] caution themselves and not blindly follow where crypto bros lead,’ he says.

The digital revolution has also brought direct smartphone-based market trading. In 2021 consumer investors eviscerated the short positions of several hedge funds by buying stock in retailer GameStop. It surged 1,500 per cent, causing the hedge funds to lose billions. Costa describes this as ‘an almighty F.U. to the system’. Zennials used ‘their newfound tools and collective organisation… to go to war against the old guard’.

Perhaps unsurprisingly for a career banker, he warns that by removing the professional advisers, direct trading also exposes the investor to greater risk. Noting the FCA warning in 2022 against ‘gamification’ of stock trading apps, raising a comparison to gambling, he adds it ‘found that consumers using apps with these kinds of features were more likely to invest in products beyond their risk appetite’.

When combined with the social media revolution that enables instant worldwide communications and organised responses, as seen with the Black Lives Matter campaign (incidentally, Costa joined the movement’s London rally in 2020), the foundations are being laid for a potential financial collapse like never before.

‘The changes that have taken place philosophically, sociologically and technologically over the last two decades are analogous to that of the Manhattan Project,’ cautions Costa, referring to the Allied programme to develop the atom bomb. ‘It will, and has, changed the world for ever.’

So how do we stop the bomb going off? Costa’s answer sounds deceptively simple. He says the generations must come together in an environment of mutual respect, to listen, to engage. Boomers have to hold their hands up and apologise for their mistakes and the young, in return, need to forgive.

‘This is the key to saving capitalism’

‘Intergenerational collaboration is the key to saving capitalism,’ he writes. This intergenerational amity is expressed in his idea of ‘CO’, inspired by notions of collaboration, compassion and community, ‘where what we give up is less than what we gain’. Importantly, it falls well short of collectivism. ‘If we can break down the stereotypical silos, then we can find bases on which we will be able to work together – the hindsight of my generation, the insight and creative insight of the next generation – to create a lively, vital capitalism that pays attention to the broader issues, rather than just the bottom line.’

As for practical steps, he advises Boomers and Gen X to ‘invest alongside’ Zennials – the older generation has the capital, the younger ones have the start-ups. ‘That’s what I’ve done,’ he says. ‘And it’s not just investing, [the Boomers] can mentor, coach and win the trust of that generation; they can say to them, “I’ve seen booms, busts, inflation, I’ve seen it come down and go up.”’ (He goes further in his book, writing: ‘I would say that investing in the Zennial generation is as good an act of charity as donating to an NGO, perhaps even better.’)

The young can also hire the old and benefit from their experience. Citing the example of crypto exchange FTX, which collapsed in 2022, Costa notes that ‘there was no oversight from an experienced board of directors’, adding: ‘A group of older people… would have put in place processes, clear corporate procedures and risk controls that come naturally to my generation of corporate executives.’ Had they done that, the ‘disaster could have been avoided’.

In addition, leadership needs to change to be more consensual and collaborative. ‘When the people working for you are actually realising that they are participating, that they are sharing, that their views are being taken into account,’ he tells me, ‘they feel that there’s a sense of cohesion and purpose’. As a result, productivity grows.

Beware the loss of the Boomers

Ultimately, Costa says, we need to learn how to disagree with one another, to be at peace with that disagreement and avoid giving in to the temptation to retaliate. (We need to restore our sense and faith in objective truth, too.) Both in his book and during our conversation, he quotes one of Mandela’s insights, that ‘bitterness is drinking the poison and hoping the other person dies’.

‘There are many who are anticipating the decline in influence of Boomers with a perverse glee because, with the gatekeepers gone, they will finally be able to burn the whole system to the ground,’ Costa states. ‘I understand why this seems an attractive option. But the consequences will not be pretty and they will be borne by you, Zennials, not those you’re angry at.’

In a long career of deal-making, Costa has been on the sharp end of many challenging negotiations, but attempting to bring two sides of a $100 trillion generational wealth divide together must surely rate as his biggest deal yet. At the end of our conversation I ask him to reveal the secret to great deal-making – after all, he helped the Barclay brothers to acquire the Ritz and

Mohamed Al-Fayed to sell Harrods (for a reported £1.5 billion).

At the heart of successful deal making is trust, he explains, and knowing the parameters within which you’re operating. ‘Therefore, you need to know your client very well, and the client needs to trust you, because it’s going to be midnight, the pizza would have gone cold, and the deal needs to be closed.’ With that knowledge of one’s client and a strong supply of integrity, you can ‘get the client to go to bridge a gap – because there’s always a gap’. He adds: ‘Agreed deals are always hostile until the moment of agreement or the documents are signed.’

With Boomers now in their sixties and seventies and the eldest Millennials entering their forties, we are surely close to midnight demographically speaking. The pizza is cold. The $100 trillion wealth transfer is upon us. Whether Costa’s suggested solutions will gain traction or fall upon deaf ears isn’t clear, but he has faith that we will find a way through it. Let’s hope he’s right, because our collective future depends on it.

The 100 Trillion Dollar Wealth Transfer: How the Handover from Boomers to Gen Z Will Revolutionize Capitalism by Ken Costa is published by Bloomsbury Continuum, priced £20

This story first appeared in issue 89 of Spear’s, available now. Click here to buy a copy and subscribe

[See also: Revving up in style: Concours on London’s Savile Row returns for 2023 ]