While gossip has long been an everyday part of life in Monaco, it had been rare – until recently – for substantive details about the private lives of its ruling family to be revealed without their permission. So when a series of handwritten notebooks containing the financial secrets of the principality’s most powerful man found its way into the media earlier this year, the chattering classes stood up and took notice.

[See also: Flight risk: Britain’s super-rich are on the run]

The detailed records carried embarrassing revelations about the finances and personal life of Prince Albert II, Monaco’s ruler since 2005. These included clandestine payments made to ex-lovers and habitual overspending by Albert’s wife, South African former Olympic swimmer Princess Charlene.

Then, in the summer, the scandal took a new turn when Monaco’s judiciary carried out a series of searches at the homes of people reputedly close to the prince and his late father. Apart from the embarrassment and controversy, the saga raised an important question: just how did the information get out into the wild?

[See also: The dark art of the deal: the oligarch who lost a billion in the art market]

The answer seems to lie with Claude Palmero. The 68-year-old bespectacled accountant spent 40 years managing the books of both Prince Albert and, prior to that, his father, Prince Rainier III.

In 2022 Palmero began to attract the wrong kind of attention when his name featured on an anonymous WikiLeaks-style blog called Dossiers du Rocher, which published emails from Prince Albert’s inner circle that appeared to show how a small clique of advisers (Palmero included) had used their influence to control lucrative real estate contracts. In 2023, with the scandal still rumbling on, Palmero was removed from his post as the prince sought to distance himself from the mess and dispel the whiff of corruption it had created.

But this wasn’t the end of the matter. In January this year, Palmero took the decision to break the traditional omertà of the Monégasque inner circle to give a tell-all interview to Le Monde, in which he protested his innocence and accused his former employer of using him as a scapegoat. At the same time the newspaper began running stories based on Palmero’s private notebooks – with readers left to draw their own conclusions as to how they got there.

[See also: Why private client lawyers are in prime position to lead top firms]

Even by the standards of Monégasque palace intrigue, the Palmero affair was a rollercoaster. It’s also a cautionary tale for any wealthy individual who has ever placed extraordinary trust in an adviser.

Creation of a confidant

Indeed, Palmero fits the model of what you might call the ‘right-hand man’ – a trusted confidant or consigliere who occupies a position of particular influence within the inner circle of a figure of wealth or power. We know them from literature and film, of course – think of Succession’s Frank Vernon or Mr Bernstein in Citizen Kane. But these ‘right-hand men’ (or, indeed, right-hand women) exist in real life too.

[See also: Succession at the House of Arnault: who will wear the crown?]

Discussing the Palmero case with members of the Spear’s network brings a collective nod of recognition. While many UHNWs command retinues of advisers and extensive structures, including family offices, it is not uncommon for them to trust a single employee above all others.

‘We certainly encounter these figures in our work,’ says private client lawyer Matthew Briggs, a partner in the London office of Irwin Mitchell. Indeed, in many cases it is these highly trusted in-house advisers who serve as the main point of contact for UHNWs, handling many of their day-to-day affairs with law firms, private banks and other service providers.

In some cases, says Briggs, the right-hand adviser is a former private client lawyer (or, as in the case of Palmero, an accountant) who leaves private practice to work for a client directly. Over time, their role can take on a much wider remit, covering the broadest spectrum of personal, family and business matters.

[See also: Life of a scion: what’s it like to inherit a business empire?]

‘These kinds of right-hand advisers will sometimes work as a sort of internal project manager,’ says Robert Brodrick, private client partner and chair of Payne Hicks Beach. ‘They will be coordinating the work of teams or lawyers and advisers elsewhere, including in other jurisdictions, to get what the principal needs.’

In theory, then, you can see how having such a trusted lieutenant could help a successful entrepreneur or scion to stay on top of their interests across the globe. Yet, practically by definition, many right-hand advisers also find themselves tasked with managing issues that fall well outside the boundaries of the typical lawyer, accountant or trust administrator.

The Eric Schmidt affair

Take the example of Derek Rundell, a Michigan-born entrepreneur who became the right-hand adviser to former Google chief executive Eric Schmidt, then serving as the web giant’s executive chairman, after the two were introduced by a mutual business contact in 2013. As with many close confidants to billionaires, the exact nature of Rundell’s responsibilities was not widely known – and perhaps they had never been formally documented. Yet details from legal depositions give an idea of his role. In one testimony, Schmidt described his former employee as a man expected to ‘solve special and hard problems’.

[See also: Cash and carry: is this the end of carried interest?]

One such problem arrived in 2014 when Rundell was tasked with overseeing an unconventional separation arrangement between his employer and a New York-based executive called Marcy Simon, with whom Schmidt had previously had a lengthy extramarital affair. Under the terms of the arrangement, Simon would be employed as a consultant to a venture capital fund owned by Schmidt. She would receive a monthly salary of $47,500 and additional bonus payments for any investments she sourced that met the necessary criteria. Rather than deal with her former lover, she would deal exclusively with Rundell.

By 2019, relations between all three parties had soured considerably. When a commercial property dispute (over the ownership of a 40-acre horse farm) led to Schmidt taking legal action against Rundell – by now his former confidant – the situation took a dramatic turn. Rundell filed his own suit, making reference to some of the more lurid claims made by Simon against Schmidt, including that Schmidt had used illegal drugs and engaged with prostitutes. Lawyers for Schmidt moved to deny the allegations, but the damage had been done: details of the claims were now on record.

How to find a trusted adviser?

The Palmero and Rundell cases might be dramatic. But they reflect the risk of allowing someone who was once ‘just an employee’ into one’s circle of trust, and of exposing them to highly private and personal information.

The most important step principals can take to mitigate such risks is to ensure their advisers have shared values, says Kedge Martin, the former chief executive of Sentebale, the HIV and Aids charity co-founded by Prince Harry, who now uses her expertise to advise UHNWs and family offices: ‘You need someone not only with the competence for the job, but who is aligned with your values and who wants to work with you for the right reason.’

[See also: How do you hire the right family office head?]

How to find such a person? Many HNWs choose to hire someone who has already earned their stripes via an existing relationship. In 2016, for example, Elon Musk hired one of his bankers, Morgan Stanley VP Jared Birchall, to run his new family office. Birchall had reportedly proven his usefulness by obtaining loans for Musk when the Tesla chief was facing a liquidity crunch.

Whisper networks can play a big part too. ‘Referrals and recommendations are very important when it comes to hiring close advisers,’ says Martin. Crucially, she says, UHNWs should wait until they are entirely convinced before bringing anyone into the inner sanctum. ‘It’s like that phrase about how it’s better to have an empty house than a bad tenant.’

Bad news for the ‘next gen’?

For founders and entrepreneurs, due diligence is par for the course. But a transfer of wealth to younger members of a family might mean the ‘next gen’ find themselves facing decisions beyond their experience. As a third-generation heir to the Getty dynasty, Kendalle Getty was in her early twenties, and only recently out of college, when she was introduced to Marlena Sonn – a recently minted wealth manager looking to carve a niche providing ‘progressive’ solutions to HNWs with a social conscience – in 2013. The two hit it off, and Sonn was hired to manage the money that had already been passed to Kendalle and her younger sister Sarah. According to court documents, Sarah came to regard Sonn as an almost maternal figure, providing a kind of mentorship that she didn’t receive from her own mother. In texts, Sonn would refer to Sarah as ‘babe’.

[See also: The best wealth managers for ultra-high-net-worth clients in 2024]

Eventually, though, the heiresses found themselves at loggerheads with Sonn, as disagreements about competing philanthropic causes became ill-tempered rows. Sonn had also alienated her employers by seeking a more generous compensation package. In 2021, both sisters terminated their employment of Sonn, with Sarah spelling out in a text: ‘I now don’t trust you in any regard.’

Three years later, the relationship remains the subject of litigation in both New York and California. The two heiresses accuse Sonn of breaching her fiduciary duty and manipulating them into signing off an unjustified settlement. In response, Sonn says the Gettys soured on her after she raised concerns about their potentially fraudulent tax practices.

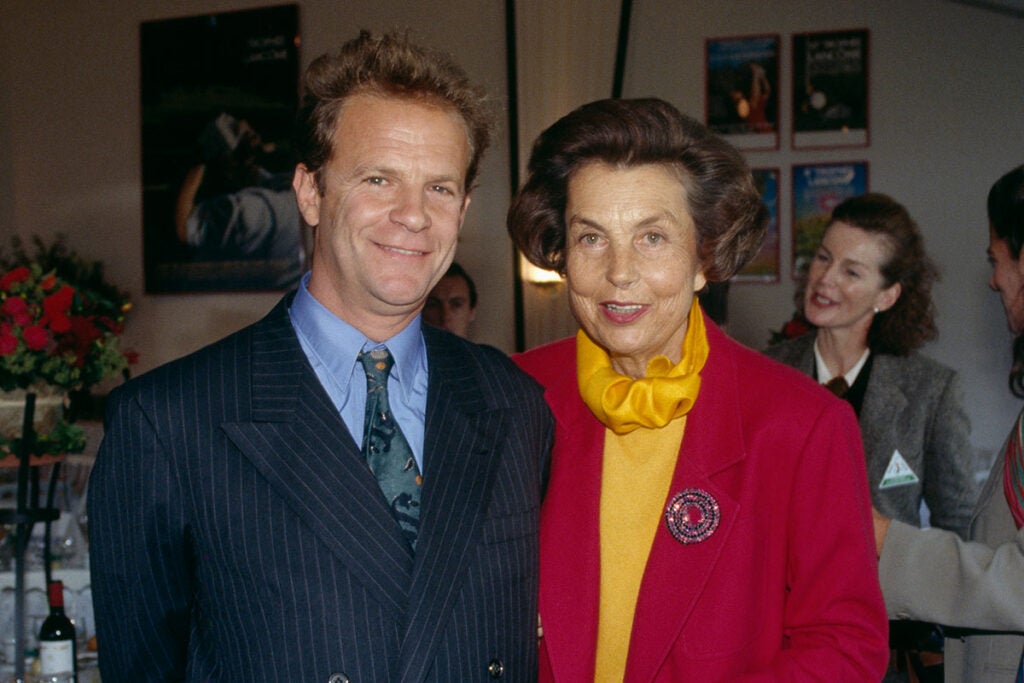

Money laundering, extortion and blackmail

Placing trust in the wrong confidant can end up contaminating other relationships too. Of the many twists and turns in the infamous Liliane Bettencourt scandal, in which the late L’Oréal heiress was manipulated into handing over money and art worth hundreds of millions of euros to a society photographer, was the fact that Ms Bettencourt’s former lawyer and wealth manager were also convicted of abusing her trust by various means, including money laundering. It was thought that the long-standing advisers had been motivated by jealousy, feeling they had been unfairly overlooked, as their employer lavished her affection – and artworks by Picasso and Matisse, among others – on François-Marie Banier, a photographer and man about town whom she had met far more recently.

[See also: The best reputation and privacy lawyers 2024]

In some cases, less scrupulous employees may even try extortion or blackmail. ‘One thing we encounter is terminated staff trying to obtain a pay-out based on their access to sensitive or private information,’ says Sofia Syed, an employment lawyer and reputation manager who advises clients on their household staffing arrangements through her firm MEUM.

Non-disclosure agreements can provide some protection, but even the most iron-clad of these can be breached or ignored. That there is legal recourse against the culprit may turn out to be cold comfort.

It’s unsurprising that many high-profile figures prefer to trust people they have known for many years. It’s an approach recently demonstrated by the Prince of Wales, who this summer appointed his childhood friend William van Cutsem as an adviser to the Duchy of Cornwall, the vast estate which provides the heir to the throne and his family with an income in the tens of millions.

‘Striking the right balance between personal trust and professional expertise in one’s advisers is crucial,’ says Matthew Briggs (speaking generally, rather than about the prince). ‘While it’s invaluable to have advisers who have demonstrated discretion and earned trust, they need to have the right skills too. Relying solely on an “old friend” can lead to gaps in professional advice.’

For many reasons, then, the selection of a right-hand adviser should not be taken lightly. And before inviting even the most trusted lawyer, banker or accountant to leave their post in private practice to join one’s family office, principals might pause for thought.

‘One of the advantages of working within a law firm is that you can have other people at your disposal,’ says Robert Brodrick. Tax lawyers working for private clients can draw on the expertise of colleagues in other specialisms, he says – or enjoy the luxury of seeking a second opinion.

[See also: The best tax lawyers in 2024]

There can be conflicting loyalties too. ‘As a lawyer, you have a duty to act in the best interests of your client,’ says Brodrick. ‘Crucially, that can mean giving them advice they might not want to hear.’ It can be more complicated, however, when you’re expected to give difficult advice to the person who signs your pay cheque every month.

Food for thought, then, for HNWs and advisers on both sides of the proverbial table. Right-hand advisers may be common in films and fiction, but the reality, as ever, is a little more complicated.

This feature was first published in Spear’s Magazine Issue 93. Click here to subscribe.