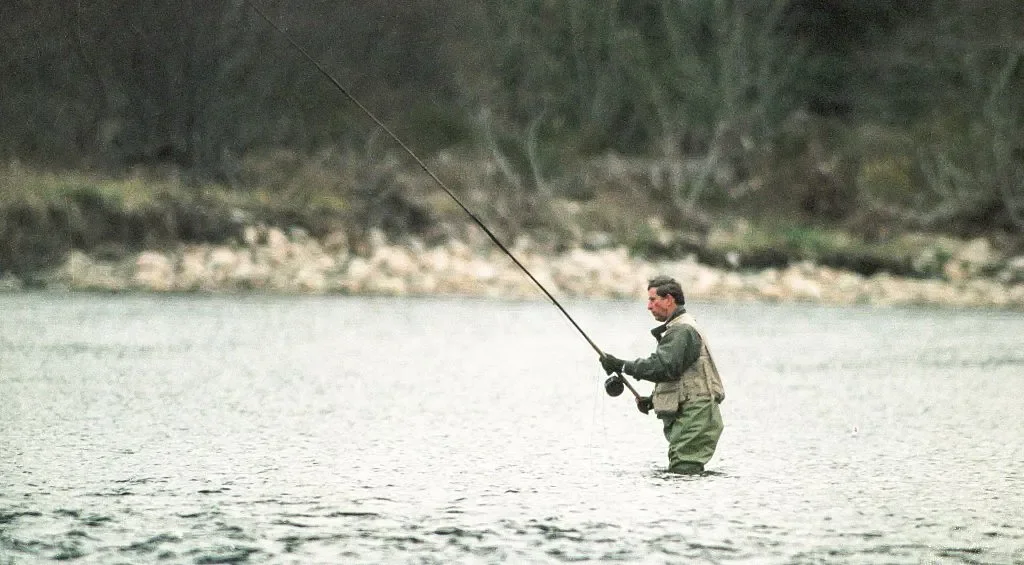

Ask any fly-fishing aficionado for their holy grail and the words ‘River Test’ are likely to rise and flap about sooner or later. This 40-mile crystal flood that arcs through west Hampshire is peerless among trout-fishing opportunities.

From May until mid-October, bankers, lawyers, surgeons and aristocrats gaze out of windows in Canary Wharf, the Temple, Harley Street and ancestral fastnesses. In their mind’s eye: a gentle meander of the Test on a summer’s day, with gin-clear water flowing over bright-green ranunculus weeds, met with willows and flowering plants, watched by ducks, wagtails and grebes, while cigar-shaped trout manoeuvre slowly beneath the surface. The image reaches deep into the hearts and wallets of Englishmen and many others.

Of the 205 chalk streams on the planet, 196 are in England. The Test is the most famous, the birthplace of dry-fly fishing that Frederic Halford pioneered in the late 19th century. Chalk streams occur when rainwater seeps through aquifers in the downs. Purified, filtered and nutrient-enriched, the water gushes from the base of the downs at a constant flow and temperature. The combination of temperature, purity and mineral largesse makes chalk streams England’s Amazon for wildlife.

Why fly-fishing on the River Test costs £350 per day

Of course, like many seductive images, this ornamental patchwork of Arcadian escapism is man-made. The Test was a silted-up, reedchoked ditch until 300 years ago. Farmers twigged that if they cut the reeds and diverted parts of the stream, not only could they create water meadows that boosted yields, but they could also fish the river all year round. Other industries piled in – water mills for wool, silk and paper, and even the River Test Gin Distillery. This seductive idyll is in fact a minutely stage-managed light-industrial waterscape.

Even the fish are a special effect. Yes, there are wild trout, but they are too small and elusive to attract fishermen paying £350 for a day’s fishing. Mottisfont Abbey estate near Stockbridge charges £400 per rod per day during ‘Mayfly’, the peak season from late May to late June when the mayfly hatches. To gratify the big spenders, the river must be stocked with large, farmed trout. This burden falls on the shoulders of the Test’s owners.

[See also: These are the best new restaurants and fine dining experiences in Monaco]

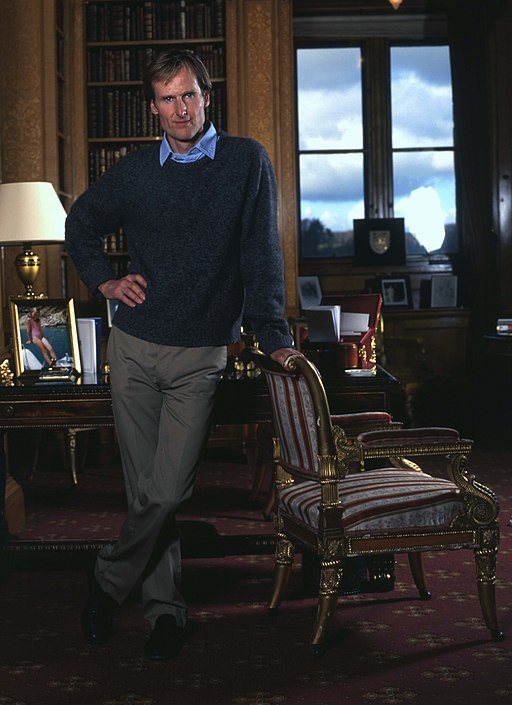

There are reckoned to be 20 owners of the Test. Among them are Lord Brabourne at Broadlands (home of his grandfather Lord Mountbatten), which overlooks the river. In Broadlands’ fishing hut, there still hangs a photograph of a teenage Prince Charles hoisting a salmon caught on one of his many visits.

An elite club owns the largest share of the River Test

Among substantial owners is John Lewis, the department store chain, which owns 12 miles. However, the whopper is the Houghton Club, which is believed to own 14 miles. Myth and legend swirl around this most exclusive club, founded in 1822. To avoid overfishing, members must not live within 20 miles of the river; it has a changing area reserved for Prince Charles (as was); the subscription is £100,000 a year, joining fee £100,000, and so on.

But the greatest mystery is how you become a member.

Rumour has it that the club adopted a catch-and-release policy towards Prince Charles, who was turned away when he had the temerity to ask to join. The club’s elite membership is topped by the Duke of Northumberland.

[See also: Highlights from Concours on London’s Savile Row]

Were an outsider to cast questions about the other members, he would be likely to get a look as if he had turned up to fish with a hand grenade. However, a glance at Companies House identifies these Knights of the Grail or Lords of the Fly as the motley cast of an Agatha Christie whodunnit: a mix of senior professionals and landed money which includes the holder of Britain’s youngest hereditary title, a novelist, a distinguished plastic surgeon, a judge and the Premier Baronet of England.

Fly-fishing on the River Test: Those with access keep a firm grip on their prize

Why so few members need so much river is another mystery. Do they hate each other that much? ‘Because they can,’ says one Test veteran. ‘The Houghton was founded with 13 members for very rich people who didn’t want others to fish their river.’

Besides a trout farm and keepers’ lodges, the club also owns the Grosvenor Hotel in Stockbridge, reborn after a £20 million refurbishment. Guests of the club are left reeling at its generosity. ‘After fishing, you dress for dinner at the hotel,’ says one.‘You only put your hand in your pocket to tip the river keepers.’

[See also: Inside the UK’s most exclusive private banks]

Elsewhere along the Test, the prestige of owning a beat ripples no further than the handful who know these things. ‘It’s not a first growth,’ says Jock Wishart, legendary Scottish adventurer and passionate fisherman. ‘You don’t want to attract wild swimmers, canoeists and ramblers. The Baring family, who own part of the Itchen, kindly let people walk their footpath. But during Covid the banks were ruined. Then thugs tore down fences. Wild swimmers aren’t so bad; they represent a voice against pollution.’

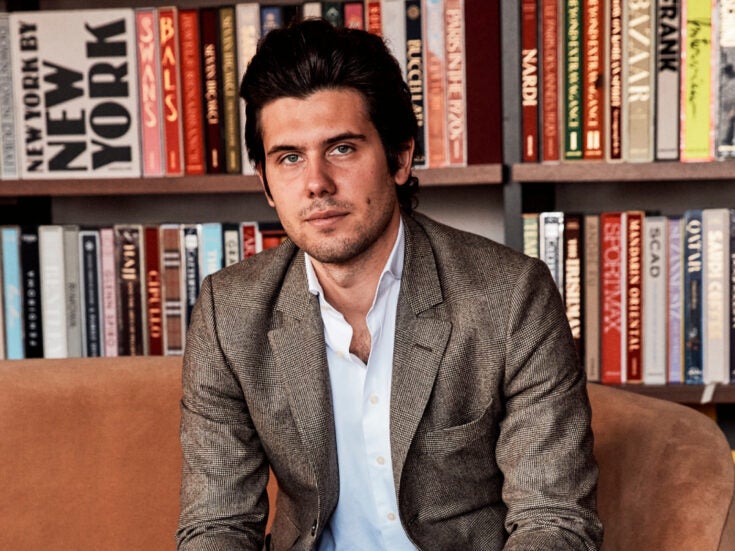

Robin Elwes, who co-inherited a beat with his cousin, says: ‘We are immensely lucky. My grandfather, a racing driver, took me to fish on the Test; it has represented an important part of my life ever since.’

Elwes has a casting clinic which promises to turn novices into plausible anglers. ‘The art of casting takes a couple of hours to get the hang of,’ he says, ‘but a lifetime to master.’ Asked about the magic of fly fishing, he sighs dreamily. ‘It is not just the chase. It’s the anticipation, the build-up, the arriving, the setting up, the casting, the hoped-for catch, and then the winding down, the storytelling and the anticipation of the next time. No need to be an expert. Anyone can enjoy it.’

As long as they can find a suitable stretch of river, of course.