Madresfield Court, a romantic and beguilingly unusual stately home lying just outside the town of Malvern in Worcestershire, has no real front and a great many sides – it is absorbingly rich in angles, both literally and figuratively. The approach, up a 2km private road that cuts through gentle meadows to the west of the house, sees its Gothic tangle of façades, turrets and accretions loom mysteriously into view against the vast backdrop of the Malvern Hills. Pull nearer and you’re presented with its full wonder: an asymmetric fantasy of chimneys, gables and bay windows amid cascades of wisteria, perched over a strikingly beautiful moat.

[See also: To the manor born: 7 best stately homes to hire this summer]

Just as you think you’ve arrived, the road curls past and deposits you on a driveway around the side, where a stone bridge leads over the moat to an oddly sepulchral entranceway ensconced in the house’s southern corner. It’s all drama and serendipity, which must have appealed greatly to Evelyn Waugh, a frequent visitor in the early 1930s, who later immortalised the place in his most famous work: Madresfield Court, and the Lygon family residing there, were the primary inspiration for Brideshead Revisited.

The Lygon clan (pronounced ‘Liggon’) have lived at Madresfield for around 900 years, a record of dynastic continuity that, it’s thought, is exceeded only by properties in royal possession. The estate, which today encompasses around 4,000 acres of largely agricultural land, has passed through 29 generations of a family whose fortunes have taken in a vast 18th-century windfall, a peerage (the Beauchamp earldom), high political offices, artistic patronages, religious devotion, some stonking parties and, 93 years ago, a spectacular society scandal.

An unlikely heiress

‘It’s gone sideways in lots of directions,’ says the current incumbent, Lucy Chenevix-Trench, describing not the architecture (though that would be apt), but Madresfield’s hereditary trajectory within her ancestry. Primogeniture can be a complicated business, especially when obvious heirs prove hard to come by. It’s something Lucy’s own custodianship demonstrates – growing up, she barely knew the place at all.

[See also: Best country property specialists 2024]

‘The fact that we’re even here is so unlikely,’ she admits over tea and biscuits in the large, welcoming kitchen that today serves as heart of family life at Madresfield. When she and her husband John, a career banker and Morgan Stanley’s former European chairman, moved here in 2012, along with their four young children, they had to get permission from English Heritage to knock some guest bedrooms together to create the kitchen.

The windows overlook the ancient moat in which the family all still swim each day, just as their forebears did more than a century ago. That was the last time there were children living at Madresfield, in the days when the estate was the domain of the 7th Earl Beauchamp, a major player in Edwardian politics and public life. His list of public service appointments was as elaborate as his home: he was leader of the Liberal Party in the Lords, a minister in the Asquith government, Lord President of the Privy Council, warden of the Cinque Ports and, at one time, governor of New South Wales.

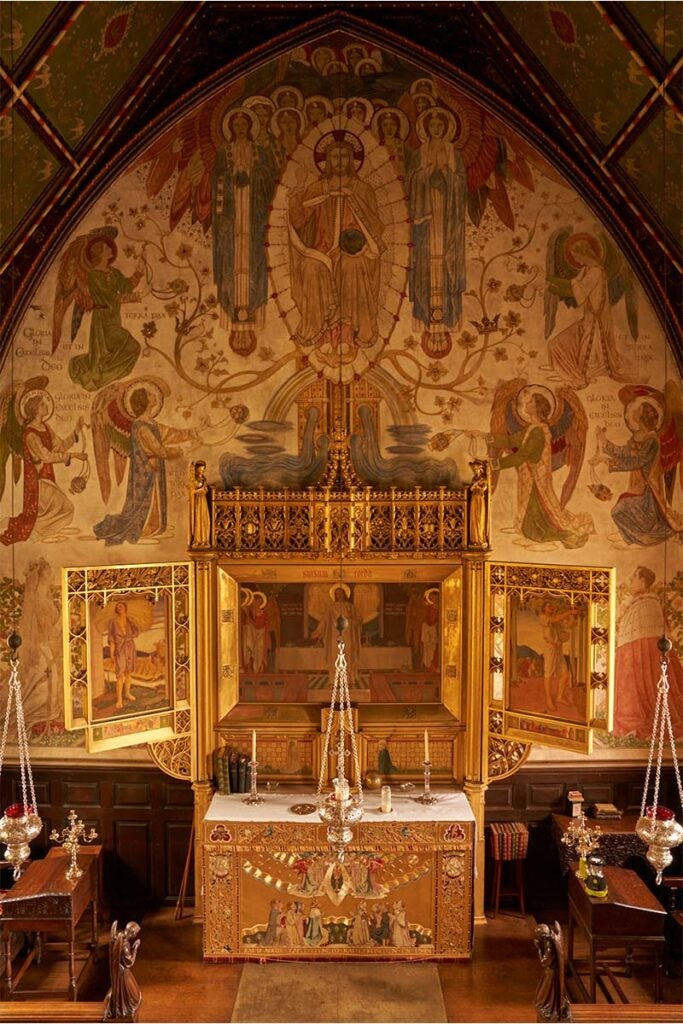

He was also a talented sculptor – as is Lucy herself – and something of an aesthetic visionary. While much of Madresfield’s exotic architecture is the result of 19th-century remodelling, under the 7th Earl it became a canvas for some of the finest work of the Arts and Crafts movement. That includes the wondrous library, decorated with relief carvings by the movement’s luminary CR Ashbee; the huge, theatrical central hall, painted black with huge inscriptions from Shelley, and a grand stairway eccentrically lined with quartz crystal balustrades; and, in particular, the little family chapel that is a dream of showstopping decorative art.

[See also: Five factors shaping the future of landed estates]

The earl was a man of radical passions in other ways, too: in 1931, he was effectively exiled after a litany of homosexual liaisons (then illegal) was uncovered, including dalliances with valets and footmen. It was hushed up, but Beauchamp’s disgrace was total: he was told he would be arrested if he ever set foot in the country again.

He had nevertheless had seven children, who adored him, and were part of the Bright Young Things whirl that brought Waugh into Madresfield’s orbit – ‘Mad’ was their nickname for the house. A magnificent portrait, by artist William Ranken, shows the entire family in all their languid, 1920s glory – it could be a still from Brideshead’s TV dramatisation, or Downton Abbey.

‘I think they had a riot of fun back then,’ says Lucy. The four sisters, known as the Beauchamp Belles, were close friends of Waugh’s, inviting him for weekends and Christmases (he even wrote Black Mischief, his third novel, while staying at Madresfield; the desk he used is still there). The capricious middle brother, Hugh – a handsome wastrel and drunkard – would be the model for Brideshead’s Sebastian Flyte; the earl himself was the inspiration for Lord Marchmain.

[See also: Why children’s literature could spell the end of pocket money]

Only two of the glamorous seven, however, would themselves have children. Lucy’s grandfather, Dickie, was the youngest. ‘He had two daughters – my mother was the youngest, and I’m also the youngest,’ she explains, underlining the tenuousness of the idea that Madresfield should ever fall into her hands. As a child, she knew it only as the home of a distant great-aunt (the widow of the 8th and final Earl – on his death in 1979 the earldom became extinct).

‘We’d visit occasionally, but it wasn’t really on my radar,’ Lucy says. ‘There was certainly no thought of ever living here.’ However, after the great-aunt died, Lucy’s mother took the decision to keep the place – and the Lygon legacy – going, beginning the job of modernising a house that had been receding into the shadows for 50 years.

[See also: Legacy is a double-edged sword for HNW family businesses, report warns]

By then, Lucy was in her early twenties. Not growing up there, she says, has dispelled any sense that sustaining it was her ancestral responsibility alone. When they were dating, she warned John of the ‘baggage’ she now came with, and by the time they moved in ‘it was a project that we were very much taking on together’. Twelve years later, the project is suddenly in start-up mode, which is why Bob Sheard, a wiry Yorkshireman in fashionable casualwear, is sitting at the kitchen table with us. He’s a branding expert who made his name in the world of sneakers and apparel, with major initiatives for the likes of Nike, Levi’s and Burberry under his belt, and an influential creative agency named FreshBritain.

Brand Madresfield

It’s with Bob’s help and encouragement that Lucy and John are now suddenly branching out in ways that, I suspect, even still surprise them.

First off, they’ve become restaurateurs: in February they opened an elegant. upmarket restaurant in Malvern, the Madresfield Butchers and Grill, with a modish menu built around produce farmed on the estate.

Then, in March, they became e-commerce entrepreneurs, with the launch of an apparel brand, Mad About Land, aimed at gardeners. Madresfield was once famed for its Victorian gardens – much-admired grape and apple varieties were raised here – and its grounds are today covered in wonderful wild flower meadows, formal gardens and herbaceous borders. Tapping into the same cultural eddies that have made Monty Don a style leader and horticulture a Gen Z life- style pursuit, Mad About Land creates mindful modern workwear for green-fingered urbanites. The name, of course, harks back to that old family nickname for the estate.

[See also: The best landscape gardeners in 2024]

Bob’s agency is doing the design work, and the clothes are being made in the United States – there’s a blue-grey utility coat, for instance, a Japanese-inspired apron, and a hardy gilet. They’ve even managed to make that hoary outdoor staple, the fleece, into something stylish.

‘I’m always struck by going to the Chelsea Flower Show and looking at 200,000 gardening addicts, and yet feeding that addiction is quite difficult once you go beyond pots and plants,’ says Bob. ‘We want to create products that are responsive and responsible, with a long functional life expectancy, and a long aesthetic life expectancy.’

It’s just the start, but in time these ventures and others still to come are intended to add much-needed income to Madresfield’s bottom line. But it goes beyond that: the projects seem to stem from an evolving understanding of the nature and responsibility of landownership itself.

Harvesting fresh ideas

While the house ripples with history and interest, it is the land, and its tenanted farms, from which the estate’s income has historically been derived, and in which John and Lucy are effecting a slow but profound change. A blossoming interest in regenerative farming has led them to begin taking back the tenanted farms and overseeing their management themselves. Over some fantastic steak in the Malvern restaurant later, John evangelises knowledgeably on themes such as soil regeneration, pasture management and mob grazing (managing the movement of cattle in a way that mimics grazing practices in the wild). It isn’t, he admits, the kind of expertise he thought he’d be acquiring in his banking days.

[See also: Introducing Spear’s Magazine: Issue 92]

‘It’s not mainstream yet, but there’s a recognition that the kinds of postwar farming methodologies that were designed to radically improve short-term yields – taking land into arable which never should have been arable, and covering it with chemicals – have done enormous damage,’ he says. ‘They’ve taken the capital out of the land and condemned our children’s futures, because the soil is getting eroded. We want to change that.’

Balanced against this is the need to make Madresfield financially sustainable in a world of rising costs and pressures. ‘At heart, it’s a very old agricultural estate, and it’s done very little else,’ John says. ‘And agricultural incomes have lagged very, very significantly behind the pace of inflation, and that places a huge burden.’

The cost increases, Lucy says, are terrifying. As well as wage inflation for the estate’s small workforce, there are soaring budgets for the continual maintenance a Grade I-listed property requires, not to mention increasingly vertiginous insurance premiums. Additionally, government legislation is making a growing headache out of the handful of cottages that are managed as rentals. ‘The regulation on let properties has gone stratospheric,’ says John. ‘It all adds costs on costs on costs, so there’s a very clear need to generate other forms of income.’

[See also: Inside the Earl of Leicester’s plan to boost ‘natural capital’]

For instance, the tourism opportunities open to some larger houses are not so viable for Madresfield. It’s an irony that it was Castle Howard, North Yorkshire’s massive Neoclassical pile, which stood in for Brideshead in the ITV dramatisation of the novel: Madresfield Court is positively bijou by comparison. You can visit for tours, but only during May and June, when it’s open three days a week. ‘The house couldn’t take more than that,’ says John, ‘but we also feel very strongly that part of what makes it interesting is that it’s a family home. It’s a living house; it’s not a historic relic.’

With their interest in land regeneration, then, could they not do a ‘Knepp’? The historic Sussex estate has become famed – and highly successful – as a rewilding haven. ‘It’s the most profitable farm in the country, and they grow weeds,’ John exclaims, with no little admiration. ‘But – and this is in no way a criticism – we do believe that we need to produce food in this country, and we want to be useful to the community here, to employ people and feed them. Ultimately, we want to show what is possible.’

[See also: Best landed estate lawyers 2024]

And after all, Knepp does rather own the rewilding brand when it comes to country estates; what Madresfield needed, its owners reasoned, was a brand of its own. That brought them to Bob, who John had met on a pal’s stag weekend in the Scottish Highlands. With him, they began working through Madresfield’s multifarious angles: the house itself, with its fairytale setting, its patrimony and its artistry; the estate, with its pastures, glorious wild flowers, gardens and farms; and their evolving views on agriculture and land management. ‘What he actually helped us with, you’d probably call a corporate strategy,’ says John.

A ‘Mad’ idea

Bob lays out his thinking. ‘As material assets these estates are quite inefficient in terms of delivering a return. Traditionally they’ve had to recapitalise by selling a farm or a piece of art or land. So in order to avoid that, we build a brand architecture where there are sub-brands that can be grown and divested off instead. There’s always the connecting thread, but when those brands get separated, there’s no negative impact on the mother brand.’

It’s an idea that effectively turns the non-tangible capital of a historic estate into something scalable. ‘I’m a real believer in the meaning of a place,’ says Bob. ‘It’s helped me loads of times to understand the potential of brands: when you understand where they’re from, there’s an energy in a place that creates choices.’

At Madresfield, he says, that energy is in the idea of the land itself, and the connection to a thriving natural environment. It’s expressed not just in the agricultural terroir and surrounds, but also in the pastoral magnificence of those Arts and Crafts interiors. It is the chapel, with its swathe of Arcadian murals, that stands as the nucleus of the entire project. The labels of the Mad About Land clothes carry an imprint of a botanical detail from the murals, which also inspired the decoration of the restaurant.

As John points out, it’s early days. There are plans to build up Madresfield’s butchery and nascent beer brewing business as associated brands too; a farm shop and further horticultural activities could one day follow, as well as platforms to disseminate related knowledge and ideas.

Madresfield’s longevity, says John, reinforces the sense that ‘you’re just custodians, and you’re trying to leave things in a better state. It’s been around for 900 years, and we need to think for the next 900 years.’ That’s a traditional enough notion, but re-imagining the estate as a start-up hub for diverse, wholesome, ecologically inspired, income-generating enterprises? That’s less so. A mad idea? Perhaps just ‘Mad’ enough.