The two-hour minibus journey, from Bhutan’s sole international airport in Paro to the capital of Thimphu, is breathtaking – and not just because your lungs have to work a bit harder at a 2,400m above sea level.

It’s fast: each turn along the winding, slightly misty Himalayan roads reveals flowing streams, scores of pine trees and majestic monasteries (dzongs), which come with dark wooden frontages and sloped red roofs.

And, it’s slow. We stop for the occasional procession of cows that moo, and then moo again, before deigning to move from our path. Then we stop again, at a main junction in Thimphu, where a jovial white-gloved police officer is standing in a small ornate gazebo, allowing vehicles to pass one by one. (Years ago, they tried out an actual traffic light – but it was removed just 24 hours later.)

[See also: Into the kingdom of Bhutan: ‘Is there really more to life than money?’]

A coveted destination

Known locally in the Dzongkha language as ‘Druk Yul’, this isolated 790,000-person kingdom is the ‘Land of the Thunder Dragon’, taking its name from a Tibetan sect of Buddhism from the 17th century. Himalayan thunderstorms are said to look like a dragon breathing fire. It’s a place to take stock, behold the valleys rich with wildlife, and admire the value people place on ancient traditions.

[See also: What to know when travelling with domestic staff, from visas to working rules]

Visitors – some of them well known – have cottoned on to Bhutan’s charms in recent years. Actor Alan Cumming visited in 2023, telling Town & Country magazine how he admired its mixture of ‘ancient and modern’, with livestock in the road and ‘prayer flags fluttering for the dead’ alongside ‘all the mod cons whenever we needed them’. (You can pick up a sim card at the airport, which gives widespread 5G coverage.)

Gwyneth Paltrow told The New York Times in 2016 that the country was on her travel ‘wish-list’, while Neil Jacobs, CEO of hotel group Six Senses, told me, in an interview for this magazine, that the landlocked country was one of his go-to destinations for an active holiday, given his love of hiking and ‘wellness’.

[See also: Six Senses CEO Neil Jacobs: Never listen to advice]

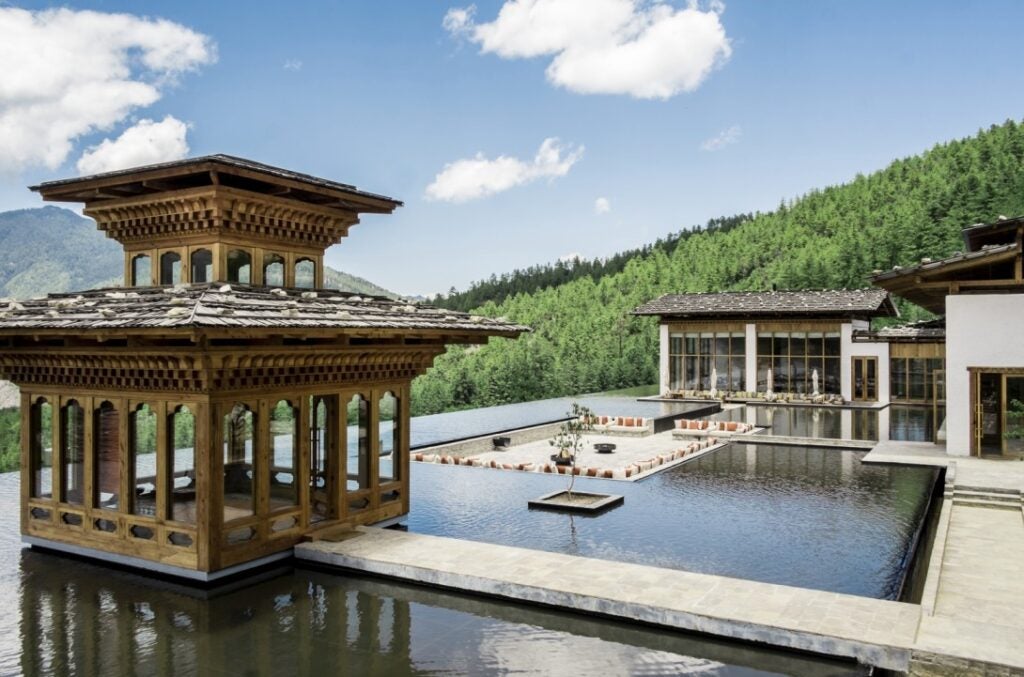

Six Senses began opening lodges here in 2018, before adding more in 2019 and 2020. And it is a Six Senses property, in Thimphu, that is my first stop on this trip.

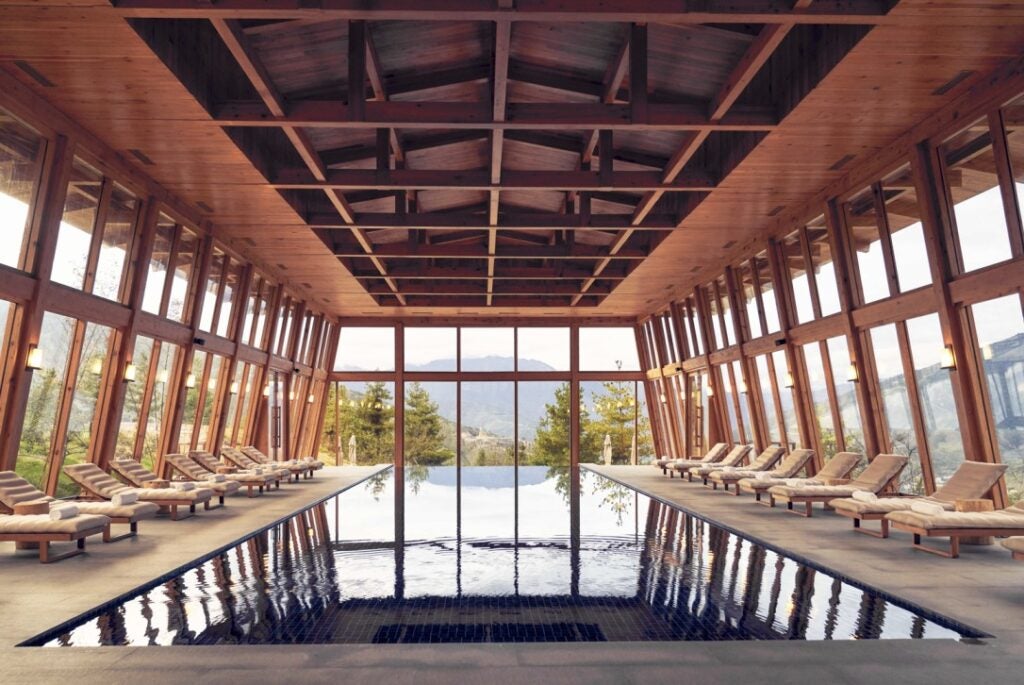

It has been constructed on a hillside between apple orchards and pine forests; there are only 25 suites here, but all of the luxury trappings, including a dedicated spa centre, an indoor swimming pool that takes in the hills through floor-to-ceiling windows, and exquisite meals prepared by Le Cordon Bleu-trained executive chef Isa Raku.

The staff are warm and kind. Once we’ve checked in and completed a tour, we jump straight into a lesson in Bhutan’s national sport, archery, given by the hotel’s managers, before unwinding with some local butter tea in the outhouse nearby.

In 1838, British army officer and adventurer Captain Robert Boileau Pemberton wrote that Bhutan’s ‘lofty and rugged mountains’ – which rise above 7,500m but also drop as low as 160m between the peaks – had meant visitors were effectively ‘shut out on every side from the rest of the world’.

[See also: Private mountain: the rare gift of Alpine skiing without the crowds]

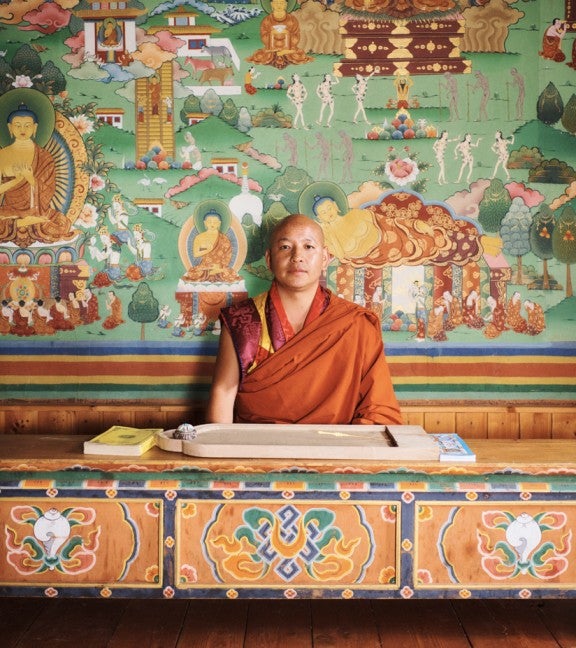

But the country’s unusual topography has given breathing space to ancient institutions such as the 16th-century College of Astrology in Thimphu, where fortune-telling monks still play an important role in guiding the Bhutanese through major life decisions.

For a long time, those choosing the monastic life lacked the disruptive influence of television, which only arrived in the country in 1999.

Opening doors

Tourism is a relatively recent development too. Borders were opened up to international visitors in 1974, the same year Bhutan’s fourth king, Jigme Singye Wangchuck,

celebrated his coronation.

My tour guide, Dorji Bidha (‘Doo-jee’), tells me a low-volume, high-touch tourism model has helped to preserve the natural environment. The 126-seater Airbus A319 that got me here from Bangkok was almost empty – aside from a handful of other travellers and the assiduous stewards on Bhutan Airlines, who plied me with extra cookies

in-flight – but I’m told around 130,000 tourists came here in 2023.

Visitor numbers are kept in check by the Department of Tourism’s ‘sustainable development fee’ of $100 per tourist per night, which would certainly rack up over a two-week excursion for a family of four.

That’s before you begin to count the cost of flights, hotels and mandatory tour guides.

[See also: Experience Seekers: The Future of Luxury Travel]

Sustainable tourism

But the high barrier to entry is serving its purpose. The World Bank says the tourism windfall has allowed the modest country ‘to invest substantially in human capital development’ and calls Bhutan’s ‘wellness tourism’ industry a new driver of growth.

The Economist Intelligence Unit, meanwhile, forecasted a healthy GDP rise of 4.8 per cent for the country in the 12 months to June 2024, fuelled by tourism and hydropower sales to India, Bhutan’s main export partner.

I see the importance of small-scale, sustainable tourism through a ‘home stay’ with Passang Om, a Bhutanese woman living in Gangtey, a rural area to the east of Thimphu. Dorji tells me she mostly runs the household here alone: ‘Her husband spends most of his time at the monastery but does come to help her when she is busy with guests.’

Om’s home is spacious, with its own temple for worship, several bedrooms and a living room with polished solid-wood floorboards. There, a certification from the Department of Tourism proudly hangs on the wall.

One night, Om teaches us the art of ‘momo’ making (Bhutanese dumplings), as we sit cross-legged on the floor in front of bowls of flour. For all the touching domestic moments like this – alongside savouring Bhutan’s ema datshi (chilli cheese) delicacy and hearing anecdotes about the lives Dorji’s grandparents led – Bhutan does not disappoint in its grandeur or the dramatic scale of its natural landscapes.

[See also: Why investors should consider investing in nature]

One morning, we trek for several miles in the Gangtey countryside, a glacial valley home to several rare wildlife species.

On another, we visit the towering, 54m-tall gold Buddha Dordenma statue in Thimphu, built between 2006 and 2015 at a reported cost of more than $100 million, part-financed by a Singaporean business magnate. Yet the scale of ambition even here may be nothing compared with what’s about to follow.

Mindfulness City

Plans are under way for the construction of a 1,000sq km ‘Mindfulness City’ in the town of Gelephu, in the less populous south of the country near the Indian border.

The project was unveiled in 2023 by the rather dashing fifth king, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, who took over the throne in 2006. (His postcard-perfect family photos are often pored over in swooning pieces on MailOnline and in Tatler.)

Its plan is to function as a special administrative region to attract new jobs, infrastructure and investment opportunities, akin to an economic hub like Singapore or Hong Kong. Gautam Adani, Asia’s second-wealthiest billionaire, is reported to be in talks to fund some projects here.

Since the Seventies, Bhutan has measured ‘Gross National Happiness’ (GNH), for which the country has become famous. The GNH index prioritises good governance, sustainable initiatives and the preservation of the country’s culture. But the young today are increasingly outward-looking: some have migrated for greater economic opportunities in Canada and Australia.

There’s hope the Mindfulness City could provide opportunities locally. ‘The world sees us as one of the happiest places on earth because of our GNH index,’ one Bhutanese woman in her twenties told me over dinner at the Six Senses in Thimphu.

[See also: Privacy, please: 9 of the best exclusive-use villas and holiday homes to rent]

‘That led to us feeling down actually, because, like everyone else, we do have problems. We tried really hard over the pandemic to fix them, through overhauling the civil service and our approach to tourism. We now have a new tourism strategy, and the Mindfulness City shows a sense of vision from our king.

Finding Bhutan

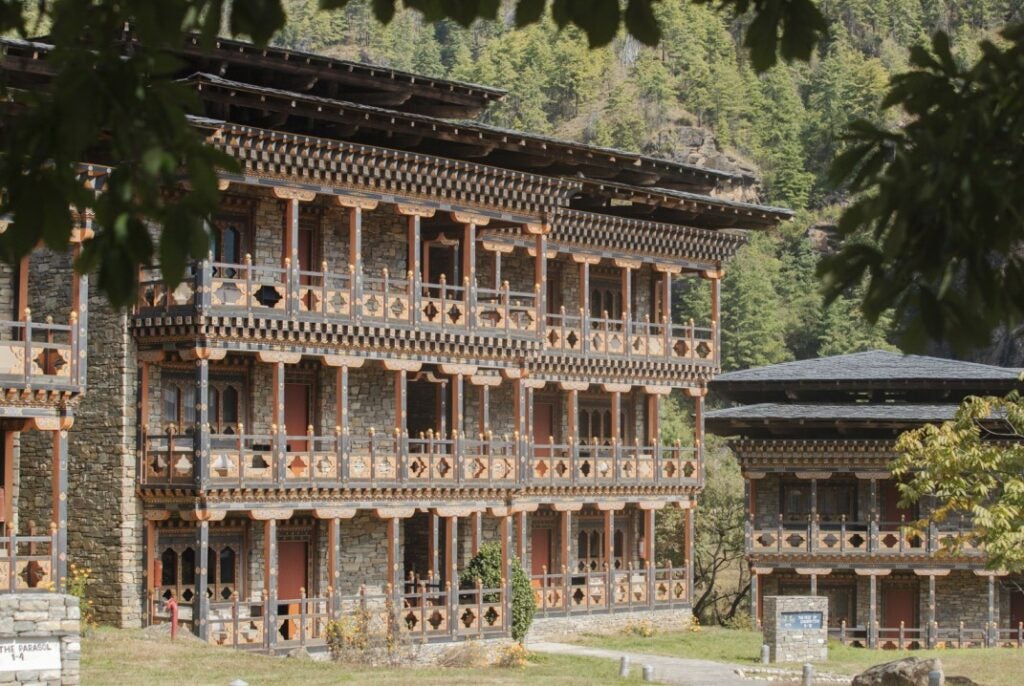

My trip comes to a conclusion with a stay in the Zhiwaling Heritage Hotel, a Bhutanese-owned establishment set over 12 sprawling acres of greenery in Paro’s valley.

The hotel architecture celebrates the ancient traditions of Bhutanese life: its upstairs temple is crafted from 450-year-old timbers which were originally part of the 16th-century Gangtey monastery. The suites here are arranged in peaceful outhouses, set by quiet hills that produce a gentle hum of insects that one can hear if the windows are opened at night.

It makes for a pleasant sleeping environment before our final hike of the trip: a 6am ascent through forests to the top of the Tiger’s Nest in Paro, where we will see the Taktsang

Palphug, a monastery that pokes out of a mountainside. It looks quite precarious, at least to those of us who aren’t quite zen enough to stop worrying about such things.

It was here, the Bhutanese mythology goes, that an 8th-century spiritual leader flew in all the way from Tibet on the back of a tigress to conquer a demon posing a threat to the local Buddhist religion.

Many monks do this walk every day, and as I climb up there are Patagonia-clad Westerners clinging to iPads and other tourists chatting away, only allowing themselves to fully take in the view once they’ve broken out into a sweat and conversation has died down.

It’s a scene that sums up some of Bhutan’s many contradictions: the collision of the old and new, the ancient and modern, a mixing of the spiritual and secular.

Before the hike, the Zhiwaling hotel’s manager of more than 15 years, a New Zealander expat named Brent Hyde, told me: ‘Bhutan won’t open itself up for you… you have to find Bhutan for yourself.’

And it is here, standing at the top of the mountain, taking in Paro’s sloping hills and lush forests below in the late-morning sunshine, that I realise what he means.

[See also: Best travel and holiday advisers]

How Spear’s travelled

- Spear’s was a guest of the Department of Tourism Bhutan, as well as Six Senses, Zhiwaling Heritage Lodge, Passang Om Homestay, Anantara Riverside and EVA Air.

- At Six Senses Bhutan in Thimphu, rates start from $2,325 (approx. £1,850), based on two sharing, full-board.

- At Passang Om Homestay in Gantey, rates start from $30 per person per night, including breakfast and dinner.

- At Zhiwaling Heritage Hotel in Paro, rates start from $845 (approx. £675), based on double/twin occupancy, including breakfast, dinner and taxes.

- Overnight in Bangkok, Spear’s was a guest of Anantara Riverside Bangkok, where rates start from approx. £140 per night, based on double/twin occupancy.

- Web bhutan.travel

- Return fares with EVA Air from London to Bangkok start at £715.59 in economy and £3,104.59 in Royal Laurel (Business) class, including all taxes and charges.

This feature first appeared in Spear’s Magazine Issue 94. Click here to subscribe