Like our own Anthony Haden-Guest, Toby Mott lived to tell the tale of the punk years. Now he dedicates his life to sharing memorabilia of the era

The hippy culture of the Sixties was both global and somewhat identikit everywhere in its behaviour patterns, its costumery (tie-dye T-shirts, bell bottoms), and its preferences in music and art (album covers, rock posters, light shows). But that was way before the internet, so it was impossible to stay wired to what was going on in other places in any detail.

Oz and The International Times covered London and we knew of ‘zines’ elsewhere, such as R Crumb’s Zap Comix, New York’s Rat and The San Francisco Oracle, but we only got to lay hands on copies late, if ever. Toby Mott, artist and hyperactive promoter of the art and memorabilia of punk and post-punk, has no such problems.

He launched Cultural Traffic, his collection-cum-mobile gallery, at London’s Truman Brewery in 2016 and plays the international network of art fairs and art-book fairs like… well, punks didn’t play the piano much, but you get my drift. Mott was born in 1964. ‘I was a punk kid since the Seventies, growing up in Pimlico, adjacent to the King’s Road,’ he says.

A punk micro-enclave was usually to be seen sitting, hair radiant, expressions less so, on the benches by the Royal Hospital.

‘Punk took over my whole life. It took over my identity at a very young age and it informed every decision I made thereafter. Like most people in London my age, we stopped looking like punks by 1980, but the imprint had been made. The punk ethic formed us.’

Getting shirty

Some personal memories might be to the point here. I had a studio in the Pheasantry on the King’s Road at that time and Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren’s boutique-of-many-names had launched up past the bend.

I knew McLaren somewhat, dropped in, looked over the offering of metal, leather and rubber fetish fashions, and eyed a T-shirt covered with names.

I had seen photographs of rock stars wearing just this T-shirt, like Johnny Thunders of the New York Dolls. Then I saw that my name was on the shirt. It was on a list headed ‘People Not To Wake Up Next To’. ‘What’s this?’ I said to McLaren, miming outrage. ‘Well, you’re an old hippy, aren’t you?’ he said, reasonably.

That was punk. Michael Dempsey, who published an early book of mine, also became a convert to punk. He managed a band, the Adverts, and published 100 Nights at the Roxy, an account of performances at a short-lived club, sometimes described as a punk bible. He died when falling off a ladder while changing a lightbulb. That was kind of punk too. I miss him.

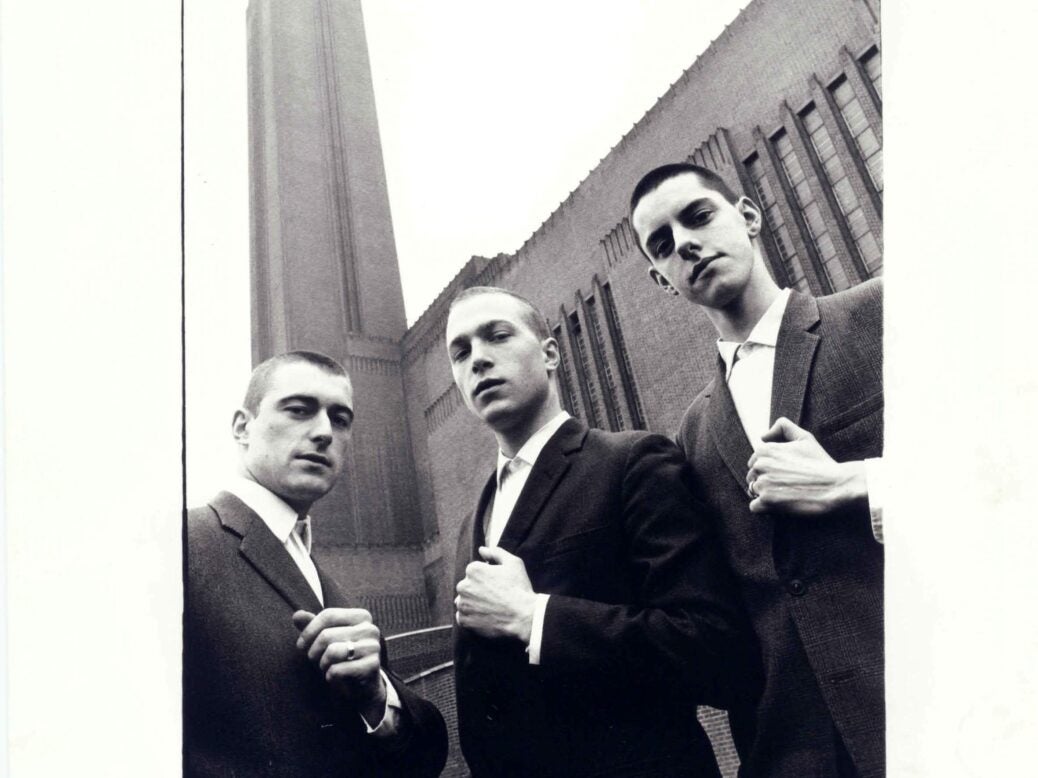

Mott was soon getting up to lots of stuff, aside from making his own art, such as appearing in several Derek Jarman movies and on art pieces by Gilbert & George, one of which is in the Tate Colelction. In 1982 he and a couple of schoolfriends formed an art collective, the Grey Organisation.

‘It was born out of some kind of business deal,’ he says. They wore grey suits and white shirts, went tieless, and carried out various actions to shake up the arts establishment, their most widely noticed being the Cork Street Attack. ‘We were frustrated with the arts establishment that kept everything locked down and it was all centred on that one street,’ Mott says. ‘So in the middle of the night we threw grey paint over all the glass windows of the galleries as a statement and an action.’

James Mayor of the Mayor Gallery, one of the targets and a pillar of Cork Street to this day, looks back on the incursion tranquilly. ‘Grey was a misnomer,’ he says. ‘They brought some colour into rather a grey scene.’ Not everyone was so philosophical ‘There were repercussions,’ says Mott. ‘We ended up decamping to New York and showing with the Civilian Warfare Gallery.’

Mott returned to London in 1995 and has moved on from being a punk activist to punk collector and archivist. Trawling the Mott Collection on the Cultural Traffic website is to be confronted with vivid visual history, sometimes historic, such as Jamie Reid’s graphics for the Sex Pistols, sometimes strident or touching, and often radiating aggro, via teeth-baring skinheads, a red-lipped Mrs Thatcher, a zipper-lipped Queen.

DIY culture

What we don’t see is interesting too. Rock was a dominant form but aside from, say, some Ramones material, rock is a non-presence on Cultural Traffic. Why? ‘We’re about the ethos of punk, which is the DIY culture,’ says Mott. ‘Punk in the Seventies, in the UK especially, went directly into the visual culture, including fashion, art, writing, publications and, of course, music. And also the idea of starting up small businesses and collectivism. Punk was the springboard for that, and it’s still going on today… And it’s different from what happened in the Sixties. Their idea was doing things together and having a purpose; this was more about channelling the energy of anger and frustration and putting it into something creative.’

Nor, for Mott, should punk be limited to the bare essentials of, say, Johnny Rotten hollering: ‘No future!’ There’s plenty of techno on the Cultural Traffic, such as images of the German band Kraftwerk, including the graphics of the New York-based designer Hubert Kretzschmar.

Does Mott see techno as an outgrowth of the punk aesthetic? ‘Yeah! Kraftwerk in particular. They are an anomaly, included in punk and included in disco. They are maybe the only band to have bridged that gulf.

‘Then all those synth pop groups – Boy George, Duran Duran – they all came out of punk. They’re very melodic. But good punk is like a pure pop song. I was watching this documentary about Joan Jett, and the guys who did bubblegum pop were writing her punk songs and they didn’t seem to see too much difference.’

Rock is dead, I said. But punk is still alive. It’s everywhere. Why is that? ‘I wouldn’t say punk music is alive. That’s a nostalgia that I’m not interested in. But the philosophy of punk is very much still alive, and that has gone into something different, something which you and I would probably find repulsive – and that would be the sign of it being very good. But I can’t bear to be presented with punk revival stuff.’

Enduring ethos

How many art and art book fairs does he do in a year? ‘Six, seven. We do Los Angeles, Detroit, London, New York. But what we do isn’t really an art fair, because our offer is affordable, it’s inventive, and it’s not about investment or speculation. We’re not comparable with a Frieze or Art Basel; we see ourselves as a hub of creativity.’

The documentation on the Cultural Traffic website includes a fragmented text by Mott himself, which seems to indicate that he believes the putting together of his collection could only have been done to deal with a movement from that time period. By this logic, equivalents to punk today might leave no records to memorialise them whatsoever.

Does he truly believe that? ‘Absolutely,’ Mott said. ‘We collected all this stuff. But that kind of came to an end… when? Twenty years ago or something like that, when it all went digital. But there’s no security in any of that, because everything is saved on hard drives and PDFs. It’s not even ephemera. It doesn’t exist as anything. People’s whole personal histories can disappear when they lose their iPhones.

‘So it’s kind of bizarre. If there’s a solar flash or something the whole culture could be wiped out. We could all be living in the absolute present when all that stuff is lost. Which in a way might be kind of… quite nice.’ And just how punk is that?

This article first appeared in issue 69 of Spear’s magazine, available on newsstands now. Click here to buy and subscribe.

Photography from Toby Mott’s collection