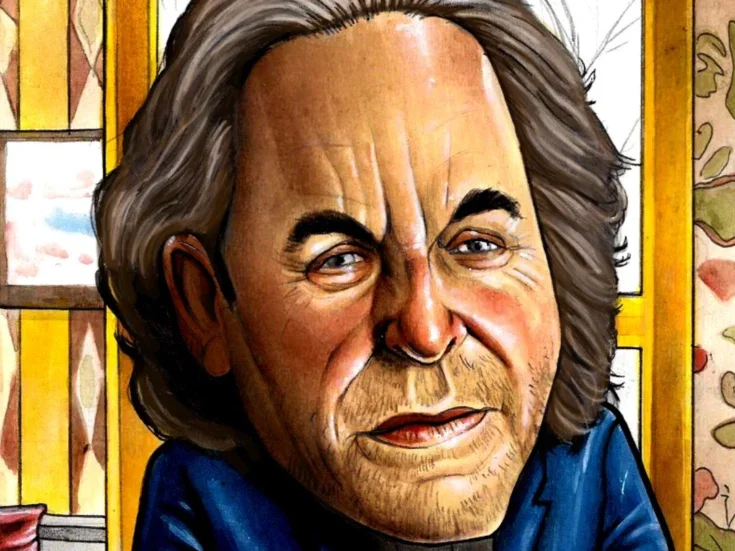

Kricket, a rising star of London’s Indian restaurant scene, is the brainchild of two unlikely Asian food heroes, writes William Sitwell

If there is such a thing as a cultural monopoly, it is surely alive and well in the UK Indian restaurant scene. From the Bangladeshi restaurants that opened across the country in the 1970s, to the grander likes of London’s Bombay Brasserie in 1982, to the posher establishments such as Tamarind, which started in 1995 and achieved a Michelin star in 2001, they are Asian-owned and run.

Even today, as new establishments open such as Mount Street’s Jamavar or Brigadiers in the City, they are owned by wealthy Asian families and businesses, many of whom recruit their staff directly from India. Then, in 2015, something unusual and radical happened. Two white middle-class boys rented a shipping container in Brixton and started serving small plates of Indian food.

It was an immediate success. Two years later, Kricket won Best Newcomer and Will Bowlby scooped Asian Chef of the Year at the 2017 Asian Curry Awards, though the pair knew nothing of the nomination and weren’t invited to the ceremony. Today, Kricket – rather like the dishes it serves – is a small but perfectly formed part of the Indian restaurant scene.

Today there are three Krickets: one in Soho, another near the original sea-container location in Brixton, and a third at Television Centre in west London. With Bowlby taking care of food and his partner and old university pal Rik Campbell running the business, they are an impressive and effective duo.

Having worked under the great British chef Rowley Leigh after graduating, Bowlby was headhunted for a job at a restaurant in Mumbai. Once back in London, he sealed his Indian cooking experience with a stint at Vivek Singh’s Cinnamon Kitchen. He then teamed up with Campbell, taking the plunge when they got a Pop Brixton 20-seater container.

Their little plates, crafted with culinary know-how but tailored for London palates, didn’t just excite the city’s foodies. Bowlby and Campbell were immediately courted by businesses looking for concepts to roll out. But they declined, as they still do.

East to west

The quiet, thoughtful, coolly dour Bowlby, now aged 30 and with a first cookbook under his belt, is still turning down offers to sell the business.

‘I’m riding my luck,’ he says. We chat in the dining room of their latest opening, in the redeveloped old BBC location next door to White City House, another outpost of the Soho House clubs.

The new Kricket is, says Bowlby, ‘slow burn’. With an outside terrace the capacity is 140 covers, but they are still waiting for six more floors of offices to open and other residential space to be occupied.

‘We’ll ask the landlord if he’ll consider extending our rent-free period,’ he mutters. There are no imminent plans for a fourth Kricket.

‘This year we’ll sit on what we have,’ he says. ‘I am now physically cooking a bit less – which is a strange adjustment as I’m a chef, but it’s a different kind of role. I’m still in one of our kitchens every day, but I’m not quite doing the hours I did, although there is still really no such thing as a day off.’

Bowlby’s other priority is his staff. ‘We do our very best to look after them,’ he says, before adding something that may ruffle feathers in the mainstream Indian restaurant scene. ‘We treat our staff better than other Indian restaurants. Some of their practices are appalling.’

He continues on this theme. ‘I do not like the way Indian restaurants in London operate. It’s incestuous and the way they behave…’ It’s a practice he says is ‘something I don’t like to get involved in’. Bowlby also looks at Kricket as a refuge for chefs in his corner of the industry. ‘I like to see us as a safe haven for people who like to cook Indian food in the right conditions. This is not the case in all Indian restaurants.’

One major issue he cites are the tight obligations that many Indian restaurants force on their employees. There are, he says, ‘contracts that say you have to work for X number of years, that you can’t work for any other Indian restaurants. To me the whole point of being a chef is to cook somewhere and then to move on and learn. Why tie them in contractually?’

Such working practices are, he says, ‘probably cultural, from India’. But this is not, he is firm to stress, the experience he had at the only Indian restaurant that he worked at in London, Cinnamon Kitchen. ‘I was looked after there. But what happens in the industry I have heard and seen since opening Kricket.’ Bowlby has faced no personal animosity from the business, however.

Recently attending an industry event at the House of Commons, he was, he says, ‘in a room full of Indians and they were all incredibly nice to me’. As a white British male cooking Indian food, he will have been acutely aware of the criticism Jamie Oliver faced last summer when he created his microwaveable version of jerk chicken. The black MP Dawn Butler demanded that ‘this appropriation from Jamaica needs to stop’.

So is Bowlby bastardising Indian food? ‘When we opened Brixton some Indian customers did question this and that, but the majority liked it,’ he says. ‘I’m interested in the history. I taste a dish, I read up on it and then think, “How can I adapt it and make it better?” Indian food has evolved and is evolving, so I think I have licence to continue. I’m not putting tikka in a burger or on a pizza. I think can we adapt it to improve it; if not, we leave it.’

As to the future, one day he could take coals to Newcastle. ‘My dream is to open something in India, in the countryside or at hill station,’ he says. Meanwhile, there is one remaining and unusual irony that he hopes he might be able to deal with.

‘When I was working in India I got a serious parasite which has affected what I should and shouldn’t eat,’ he admits. ‘I can’t really eat Indian food. I’m tasting every day. But if I had a whole meal at Kricket I’d be in trouble.’

William Sitwell writes for Spear’s

This article is published in issue 67 of Spear’s magazine, available on newstands now. Click here to subscribe