Sophie McBain returns to Tripoli on the first BA flight from London to see her former home, now free, and to investigate a very suspicious death

HAVING FOUND MYSELF on the last BA flight out of Libya in February 2011, as revolution spread to the streets of Tripoli and the government began its bloody crackdown, it only seemed right to return on the first BA flight back into the country now known as Libya al-Hurra, ‘Free Libya’. Nostalgia meant I had almost missed the cheerless, dimly lit arrivals lounge at Tripoli International Airport, with its curling propaganda posters, hostile border guards and mysterious clusters of chain-smoking men in ill-fitting suits barking down their mobiles.

But the airport was different this time round. A group of ground staff had gathered around the plane to film our arrival on their phones — the resumption of BA flights was cause for optimism, a sign that normality, and with that foreign business, was steadily returning. ‘Welcome back,’ said one cheerfully from behind his smartphone, another handed out roses from BA, and even the men at passport control seemed friendlier now, less reluctant to wave me through.

The city looks and feels different. It used to amuse me that the only graffiti I saw during the Gaddafi era was the occasional ‘God is Great’ scrawled on a wall, a sentiment that few Libyans would seek issue with. But Tripoli now is an open-air gallery for anti-Gaddafi street art of varying quality and inventiveness: SpongeBob the revolutionary is a personal favourite. The old Gaddafi posters are gone and the new Libyan flag has been painted on shop fronts and unfurled from windows; new cafes are mushrooming across the city, filled with macchiato-lovers and excited political debates; couples are holding hands in the streets; NGOs, magazines and newspapers are launching almost daily.

But this freedom was hard-won. While the serious damage in Tripoli remains remarkably limited to the military targets bombed flat by Nato, other buildings bear the scars of gun and shellfire. The posters of martyrs found on every street — young, baby-faced men photoshopped against images of white doves or Libyan flags — offer a grim reminder of the lives lost, the human suffering inflicted. Every man in Libya now owns a gun, and skirmishes between rival Tripoli militias are frequent, though most of the daily shooting is celebratory — for £25 you can hire an anti-aircraft gun for a banging wedding party.

The financial costs, of the war and of the Gaddafi era, are huge and hard to quantify. Tripoli’s potholed, dusty roads and crumbling architecture offer few hints of Libya’s wealth — with its six million-strong population sitting on the largest oil reserves in Africa, it ought to be seriously rich. Little wonder that some Libyans are now looking from their measly public-sector pay cheques to their underequipped hospitals, failing schools and ageing infrastructure and wondering where on earth all the billions went.

At the time of the revolution, the Libyan Investment Authority (LIA), Libya’s sovereign wealth fund, had around $65 billion invested around the world and the National Oil Corporation (NOC) handled revenues from a pre-war oil output of 1.6 million barrels per day. Leaked documents reveal puzzling multi-billion-dollar discrepancies on their accounts. The 2011 UN sanctions froze around $19 billion of assets controlled by Gaddafi and his associates — but some believe their actual wealth to have been still higher.

Tracing and repatriating these stolen assets represents a considerable legal challenge. It doesn’t help, for instance, that there is no international framework governing the process, so assets will have to be retrieved on a country-by-country basis. It will be politically challenging, too, as many mid to top-level bureaucrats in Libya today participated in the former regime’s corrupt practices and will be resistant to investigations. And finally, it may also be dangerous.

One person who knew significantly more about Libya’s finances than most was the former head of the NOC, Shukri Ghanem. On 29 April 2012 Ghanem was found dead in Vienna. Early news reports claimed that he had died of a heart attack at home, while later ones said he’d been found drowned in the Danube a few hundred metres away. His daughter reported that Ghanem had complained of feeling unwell the night before he died, and the Vienna police say they have no suspicion of foul play, but they have appointed a top murder investigation unit to examine the case.

NO ONE I spoke to in Libya believed that Ghanem died of natural causes. Abdelhamid El Jadi, a Libyan banker and anti-corruption activist, believes he was murdered because of a decision, made shortly before his death, to reveal the location of billions of pounds of hidden Libyan assets in exchange for judicial leniency. According to El Jadi, Ghanem spoke a few days before his ‘sudden inability to swim’ to two lawyers, one from London and one from Libya, who proposed cutting a deal with the Libyan prosecution.

Spear’s managed to trace one of the lawyers who spoke to Ghanem before his death. The lawyer said he had spoken to Ghanem on several occasions in the weeks before his death, and that he’d been hoping to get to the stage where Ghanem agreed to disclose information on his financial dealings in exchange for immunity from prosecution. He confirmed that he had indeed spoken to Ghanem for ‘five or six minutes’ just a few days before his death. Ghanem had been ‘anxious’ about his listing on Interpol (they were preparing a red notice arrest warrant for him) and the lawyer had again advised him to contact the Libyan attorney general to propose the aforementioned deal.

None of this offers any decisive evidence either way, though Ghanem would not be the first Libyan to be murdered abroad for his politics, and El Jadi knows better than most the dangers of unearthing high-level corruption. For almost ten years he operated under the pseudonym Tamil Zayat to publish examples of corrupt practices he discovered, first as a former employee of Libyan downstream oil company Tamoil and later through a network of contacts who fed him information. His former associate, Najwa el Beshti, an erstwhile employee of the NOC, alleged in a 2010 report that government oil contracts had been deliberately post-dated and assets undervalued, and that money had gone missing. In November 2010, she was in a near-fatal traffic accident. After she returned from hospital, state security officials visited her home to tell her that next time she might not be so lucky.

El Jadi is now preparing to publish data that he says will implicate around 200 individuals in the stealing of billions of dollars. He says he cannot announce more detail yet, for ‘legal reasons’, but says it’s a matter of sorting out ‘details, rather than fundamentals’. ‘Billions of dollars seems like a small word to describe what’s there,’ he adds. ‘For 42 years there wasn’t a day when they did not steal money in one form or another. If you stole big money, oil money, for 42 years, I think your bank account would be very, very huge, and that’s exactly what happened.’

The big money is already attracting corporate interest. A friend working with a Libyan ministry showed me a proposed contract from the US law firm Patton Boggs offering to assist the government in recovering misappropriated assets for a fee of 2 per cent of any assets successfully recovered. I spoke to David Tafuri, partner at Patton Boggs and the contact listed on the letter. He said he had been involved in so much correspondence with the Libyan government that he couldn’t recall that specific letter, adding that, due to client-attorney confidentiality, he could not reveal any estimation of how much money he hoped to recover, any indication of legal strategies that might be employed when tracing and recovering these assets, whether his offer had been taken up, or how much would have to be recovered to make the 2 per cent fee financially worthwhile.

LAWYER MOHAMED SHABAN was more forthcoming. The son of a Libyan exile, he says he’s acting out of a sense of patriotism to recover stolen assets. In March 2012 he succeeded in repatriating a £10 million house in Hampstead owned by Gaddafi’s third son Saadi — a small sum when compared to the billions still at large, but it was a symbolic legal victory.

His experience provides clues as to some of the complexities that may be involved in further repatriation cases. The Hampstead house was under sanctions, but it was registered as owned by Capitana Seas Ltd, a British Virgin Islands company, and nothing suggested any link to Libya or the Gaddafis. Shaban contacted the Treasury to ask why the house had been sanctioned, and it confirmed that Saadi was the beneficial owner of Capitana. Capitana was a one-asset vehicle set up especially for the purchase of the house, and shares in the company were held in trust for Saadi. It was established that on Saadi’s official government salary as head of a military unit he could not have purchased the house. According to Libyan anti-bribery law, he also would not have been allowed to accept the house as a gift from friends or relatives.

‘The legal argument is the least challenging part,’ says Shaban. ‘It’s gathering the evidence that’s difficult. In Libya, record-keeping is very poor, partly because it’s a tactic of corrupt regimes not to have a paper trail.’ The advantage of the sophisticated financial systems in the West is that there is usually an electronic trail to follow — once you know where to start looking, which can be the hardest part. Word of mouth can be a helpful starting point, says Shaban. He has started investigating one property on the basis of a tip-off from neighbours that two more of Gaddafi’s sons, Mutassim and Seif al Islam, were seen regularly leaving and entering the property. Shaban is hoping that former Gaddafi strongmen will come forward with their knowledge of embezzled funds. Top of his list are Bashir Saleh Bashir (described by El Jadi as the ‘black box’ for Libyan investments in Africa), Seif al Islam Gaddafi and former prime minister Baghdadi al-Mahmoudi.

Bashir Saleh Bashir and Seif al Islam are both believed to possess considerable information on the inner workings of the secretive LIA, a key institution when it comes to tracing stolen assets because of the sheer size of the fund, as well as tales of widespread corruption. I had hoped to speak to someone at the LIA, and had felt encouraged by having several contacts at the fund, but they did not respond to my requests. This may be partly because the LIA is currently leaderless: the interim management team has stepped down, but no new head has been appointed. A fear of being personally implicated in anti-corruption investigations may also be discouraging many from speaking to the media. Thankfully, one banker closely connected to the fund agreed to speak on condition of anonymity. He only agreed to an interview because of his frustration with the government’s (and the LIA’s) lack of resolve in securing and repatriating Libyan assets abroad.

The source confirmed that before the revolution, the LIA ‘wasn’t functioning as a proper investment body. They had the management structures in place, but in reality, decisions were made by Seif Al-Islam Gaddafi and Mustafa Zarti, deputy head of the LIA. It was very poorly run, and run on the basis of how large both commissions and egos could be.’ It’s hard to overestimate the financial muddle bequeathed to the LIA’s soon-to-be appointed caretakers. A leaked document obtained by Reuters and published by the National Transitional Council in November 2011 asks questions like: ‘Total [LIA] resources after 2010 allocations were $65 billion, how did it become $62.956 billion?’ At another point, it queried $2.456 billion that the LIA said had transferred to the treasury but hadn’t turned up on government books.

‘What happened at the LIA was an extreme disaster,’ says El Jadi. He points to two multi-billion-pound losses involving LIA investments with Goldman Sachs and Société Générale. In 2007 the LIA invested $1.3 billion with Goldman, an investment that lost 98 per cent of its value by 2010. At the same time, Goldman took on Zarti’s brother as a paid intern, though both Goldman and Zarti denied that the two occurrences were connected. In 2008, Société Générale sold a $1 billion structured bet on its own shares to the LIA which lost 72 per cent of its value by 2010. Both banks declined to comment on these loss-generating deals.

El Jadi doesn’t believe the LIA lost the money through incompetent investing. ‘No one’s stupid in multi-billion-dollar transactions — it’s because they have personal gains,’ is his wry observation.

The source says a big worry for the LIA now is the fact that certain individuals are taking advantage of the institutional quagmire to steal assets. Investments in Africa are a particular concern, because the underdeveloped financial and economic infrastructure means that assets are harder to trace and easier to steal.

‘If I were a crook in Uganda, for example, I’d think now’s the time to steal Libyan assets,’ says Shaban, ‘because now you know the NTC isn’t going to do anything and Gaddafi’s not going to call you up and say, “Where’s my cash?” That’s the biggest worry now, that the money is seeping out.’ Again there is real money involved — the Libya Africa Portfolio (LAP) has around $7 billion in assets around Africa, and money was also channelled into the continent via the NOC and Gaddafi’s strategic gifts to African leaders.

LAP GREEN, A subsidiary of LAP specialising in telecoms, is embroiled in two legal disputes over assets that Spear’s source claims African governments unfairly requisitioned, seeing opportunity in the LIA’s instability. LAP Green is suing the Zambian government for $450 million over its privatisation, without compensation, of Zamtel, in which LAP Green held a 75 per cent stake. LAP Green claims the asset was unfairly seized, while the Zambian government says LAP Green’s purchase of the shares in 2010 was illegal. El Jadi believes that the former regime secretly sold Zamtel to the Zambian government during the war, when it needed liquidity. LAP Green similarly lost its stake in Rwandatel, a Rwandan telecoms firm, after it defaulted on debt repayments — an outcome the source says might have been avoided if the new Libyan government had acted more decisively.

‘You have spurts of enthusiasm and effort from different factors in Libya, but there’s no coherent approach to getting to grips with this problem,’ the LIA source bemoans. ‘And there’s a belief that we have oil under our feet, money is never-ending, what’s a few billion here or there? And you could argue that this is possibly the cost of the revolution — that in the long term, if we lose $10 billion of assets, that’s not going to break us. But it’s ethically and morally wrong and it’s an awful, awful lot of money.’

Read more by Sophie McBain

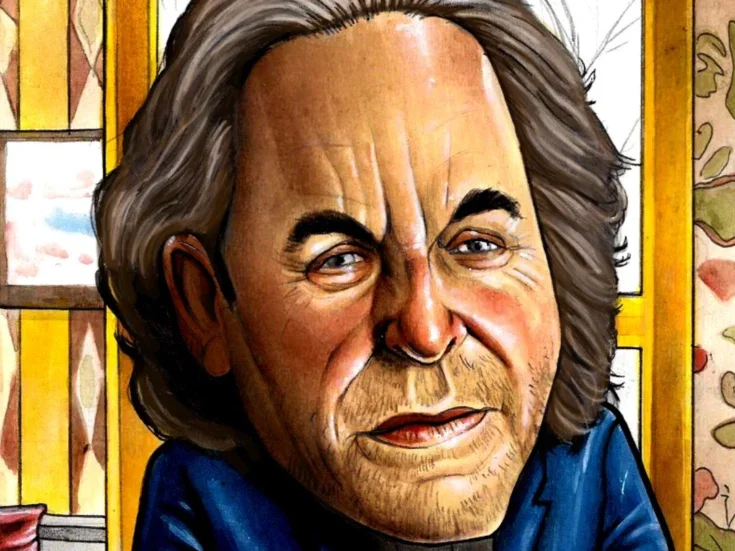

Photography by Ibrahim El Mayet

BA flies to Tripoli from Heathrow on Sundays, Tuesdays and Thursdays. Prices from £513 return, incl. taxes and charges