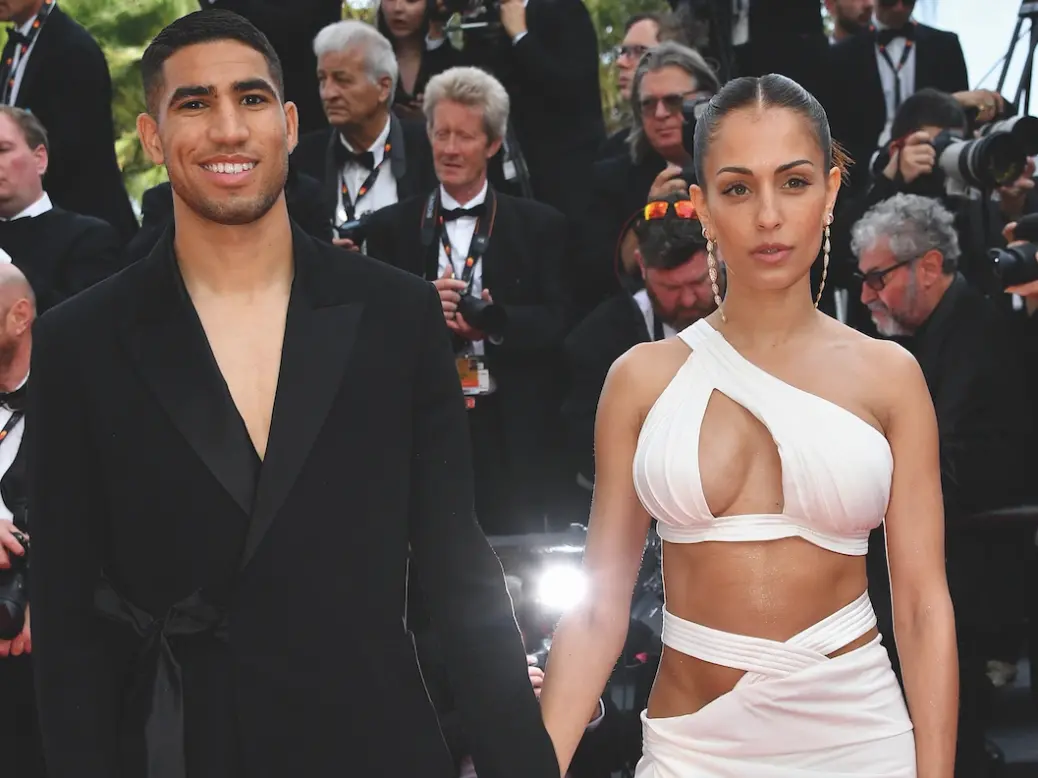

When underdogs Morocco reached the semi-finals of last year’s football World Cup, one image became iconic: the sight of star defender Achraf Hakimi embracing his headscarf-wearing mother after scoring a winning penalty against Spain.

Among the hype, one broadcaster proclaimed it as nothing short of a triumph of feminism. Fast forward six months and those feminist credentials are looking a little less secure.

In April, Spanish media reported on Hakimi’s divorce and the bombshell revelation that his mother, Saida Mouh, was in fact the real holder of his wealth – a twist that would deprive his former wife, Spanish actress Hiba Abouk, from sharing the assets.

[See also: New rules on divorce reporting: is transparency the future?]

According to some reports (disputed by at least one legal expert), Hakimi had secretly arranged for his mother to receive 80 per cent of his salary, giving her total control over much of his $24 million net worth. The unconventional arrangement would frustrate Ms Abouk’s claim to an $11 million settlement. Unsurprisingly, the case has raised eyebrows.

But could Hakimi have pulled off such a trick in England and Wales?

A straight red card

A straw poll of Spear’s most in-the-know divorce lawyers comes back with a straightforward answer.

‘Excuse the football pun, but anyone trying that will get a straight red card,’ says Howard Kennedy’s Lois Langton, capturing the consensus. Indeed, English law contains specific safeguards designed to stop such trickery.

‘Where any assets have been disposed of in the three years preceding an application for financial relief, the onus is on the disposing party to prove that the disposition was not intended to defeat a financial claim,’ adds Langton. ‘In other words, that spouse must prove a negative.’

[See also: Is London losing its libel crown?]

Spouses unable to prove their good faith risk paying a price. ‘Such conduct can lead to complete mistrust between the parties and can be a sure route of finding oneself in protracted – and costly – litigation,’ says Sarah Jane Lenihan, a partner in the family team at Dawson Cornwell. The court may order one spouse to pay the extra costs involved.

No options for hiding a large bank balance

Perhaps unsurprisingly, these hurdles haven’t stopped some less scrupulous – or perhaps, one lawyer suggests, less wise–parties from trying their luck. Earlier this year, the High Court took the bold step of ordering a full retrial after establishing that a husband had concealed from his spouse a £4 million inheritance (Cummings v Fawn). The husband, a university academic, will be forced to pay for the proceedings.

Would the sleight of hand have been more successful if the money had been held in trust? The divorce lawyers aren’t convinced. ‘The court can set aside a “sham” trust where a spouse is still benefiting from trust assets – in other words if the trust is found to be a deliberate attempt to frustrate the other spouse’s claim,’ says Lois Langton.

The idea of using cryptocurrency – touted for its anonymity – gets similarly short shrift. ‘The money has to come from somewhere in the first place, so there will usually be a paper trail,’ says financial planner Ceri Griffiths, a specialist in supporting women divorcing from richer husbands.

Family businesses: a complicated affair

But while the options for hiding a large bank balance are effectively non-existent, the reality for cases involving less liquid assets – for example, a successful family business – can be much more complex. And where complexity exists, it is possible to take advantage of it.

Earlier this year, a Court of Appeal judgment heralded the latest twist in Britain’s longest-running HNW divorce saga (Goddard-Watts v Goddard-Watts). The appeal court upheld the wife’s arguments that the husband – the co-founder and heir to a successful DIY company – had deliberately undervalued the business in order to pay her less. It has now ordered a complete retrial, accusing the husband of ‘fraudulent non-disclosure’.

[See also: How no-fault divorce will change family law in England and Wales]

When James and Julia Goddard-Watts originally divorced back in 2009, the husband put forward a balance sheet of around £15 million (of which £7.25 million would go to the wife). Since then Ms Goddard-Watts has made two successful challenges to the settlement, which she claims has left her with just a fraction of the true marital assets.

The case is far from unique, according to Griffiths, who often deals with the financial elements of HNW divorces. ‘A lot of my clients are women divorcing a chief executive or founder husband,’ she tells Spear’s. ‘I often see those husbands using things like deferred compensation – which is very common in the business world – as a way of holding back income in the run-up to the divorce.’

The big problem in such cases, says Griffiths, is that establishing the facts will inevitably trigger litigation – bringing both a financial and emotional cost on the parties.

‘I think some husbands actually try to use that to their advantage,’ she tells Spear’s. ‘They know that the divorce process is stressful, so they will make their affairs as complicated as possible to encourage the other party to settle.’

Should the case proceed to court, though, anyone pursuing a deliberately obstructive approach risks being penalised. In the 2019 case of Moher v Moher, the Court of Appeal ruled that, where one party makes it impossible to gauge the value of their assets, the courts can infer that the other spouse’s proposed award is reasonable. Those who refuse to engage, then, could end up paying over the odds.

A pre-or post-nuptial agreement ‘only option’

So what can nervous HNWs do when it comes to keeping their wealth off the table? ‘There is really one option, which is to have a pre-or post-nuptial agreement,’ says Sarah Jane Lenihan. ‘We’ve just represented a husband in upholding one in the case of MN v AN.’ The case, involving a ‘very successful finance professional’, was seen as a reinforcement of the precedent-setting Radmacher case, with the wife held to terms of an agreement she had signed in 2005.

A useful option, then, for financiers, footballers or any wealthy individuals wise enough to take it. But not one available after the final whistle.

Experts in concealed assets

Willow Brook/St James’s Place Private Clients

Financial planner Ceri Griffiths specialises in supporting women through divorce from a rich partner. Her boutique practice helps clients with the ‘huge decision’ over settlement offers.

Lois Langton is well versed in complex financial remedy work involving large settlements. Her specialisms include tax, trusts, offshore and prenups, and she acts for a number of individuals in sport and entertainment.

Sarah Jane Lenihan

Sarah Jane Lenihan is highly regarded for her expertise in complex international cases, including domestic abuse, parental alienation and safeguarding issues. She joined Dawson Cornwell as a partner in 2022.

This piece first appeared in issue 88 of Spear’s, available now. Click here to buy a copy and subscribe