Where there’s art, there’s probably jewellery. From Art Basel Miami to PAD London, jewellers court clients with sophisticated taste and budgets to match. Lavish dinners and cocktail parties are thrown, pop-ups are staged, and jewellers such as Hemmerle, Boghossian and Taffin exhibit their latest creations alongside the international galleries whose wares adorn their clients’ homes. Yet gallerist and dealer Louisa Guinness has spent the past 20 years answering the question: ‘Can jewellery ever be considered art?’

[See also: Super troupe: Ferrari fever takes Tuscany]

Guinness’s response is a resounding yes. Her eponymous gallery was the first dedicated to jewellery made by the likes of Pablo Picasso, Claude Lalanne, Salvador Dalí and Alexander Calder. She has collaborated with contemporary art heavyweights such as Anish Kapoor, Grayson Perry and Ed Ruscha. But she says that artists’ jewellery ‘is not a well understood subject. People are still surprised that many of these artists made jewellery’.

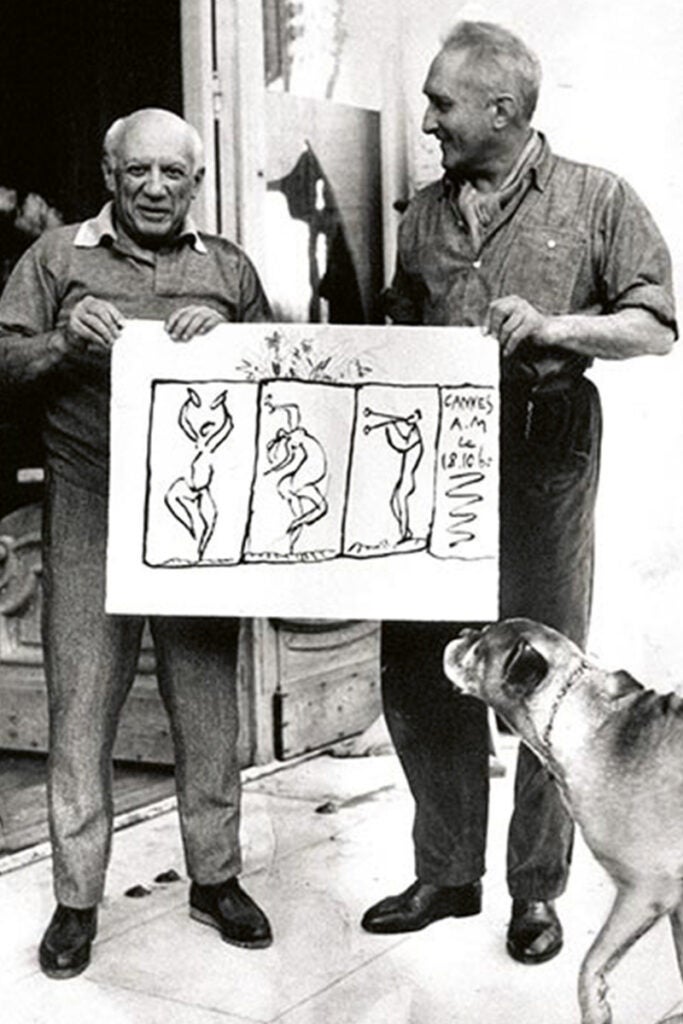

While most people with a passing interest in art are familiar with Picasso’s ceramics, Guinness says few are aware of his jewels. In the 1940s, with Françoise Gilot, he’d string bones and pebbles into necklaces. Later, with the help of his dentist, who melted down gold that would otherwise have been used as fillings, he created 22.5kt gold medallions. And in the 1950s Picasso partnered with Provençal goldsmith François Hugo on gold and silver platters, statuettes and jewellery.

Created by hammering 23kt gold into moulds cast from the artist’s models, these pieces featured Picasso’s instantly recognisable abstract faces, dancers and creatures. He originally kept them as private, precious talismans, until in 1967 he permitted Hugo to produce a limited series for sale. In March 2022 in Los Angeles, a set of 15 Picasso medallions sold at Bonhams for $350,000.

Artists’ jewellery goes under the hammer

That result pales in comparison to the $1.9 million achieved at Sotheby’s in 2013 for a silver necklace created by Calder circa 1940. Guinness describes that result as a ‘seminal moment’ for artists’ jewellery. Auctions and exhibitions have since ‘thrown a light on artists’ jewellery as collectible – like great paintings, the very best pieces are worth a lot’. The latest major dedicated sale, ‘Art as Jewellery as Art’ at Sotheby’s New York in October 2022, raised $1.7 million.

[See also: Inside the Peninsula Residences: the ultimate London trophy apartments]

Calder was a prolific jewellery artist: he created more than 1,800 pieces, hammering silver and weaving brass wire into large-scale pieces that bear the hallmarks of his sculptures and mobiles. Guinness says Calder’s jewellery commands prices akin to those of rare diamonds, partly because it was beaten by his own hand. ‘The material content is immaterial in the world of artists’ jewellery,’ she says. ‘The person who doesn’t understand artists’ jewellery might ask why you’d pay all that money for a piece of silver. But the collector doesn’t question that.’

Artists’ jewellery collectors seek pieces that echo an artist’s better known work, without simply being a scaled-down version, says Guinness. They’re driven by passion, rather than investment potential. For art aficionados, nothing compares to wearing an artist’s creation against the skin – and they’re unlikely to part with their treasures: ‘There is not a lot of resale.’

The mid-20th century was a burgeoning time for the creation of precious, wearable works of art. François Hugo also created jewellery with Max Ernst, Jean Cocteau, Dorothea Tanning, Jean Arp and Jean Dubuffet. The first ever exhibition of such ‘Bijoux d’Artistes’ took place in Paris in 1967. Meanwhile, in New York between 1941 and 1970, goldsmith Carlos Alemany brought to life in precious metal and gemstones the designs of Dalí, whose surrealist bejewelled hearts, lips and eyes were collected by millionaire Cummins Catherwood.

Today, Hugo’s grandson Nicolas crafts jewellery in the family’s Aix-en-Provence workshop, continuing his grandfather’s legacy by working with contemporary artists such as Eric Croes and Josh Sperling. And brands including Cartier, Bulgari and Tiffany enlist contemporary artists for special projects.

Blurring the lines between art and adornment

Tiffany & Co has collaborated with multi-disciplinary artist Daniel Arsham since 2021: his latest creation was a limited-edition tsavorite and diamond T1 bracelet, each one paired with a bust inspired by Arsham’s eroded bronze Venus of Arles sculpture, which is on display in The Landmark, the house’s New York flagship. The fusion of the two fields continues as a new cohort of contemporary creatives blur the boundaries between art and adornment.

[See also: The atelier bringing Savile Row-quality craftsmanship to high-powered women]

At London’s PAD in October, book publisher Taschen presented solid-gold Chinese Zodiac charms designed by Ai Weiwei, whose first foray into jewellery was a series of 24kt gold ‘wearable sculptures’ created in collaboration with London gallerist Elisabetta Cipriani. The Taschen range includes a 48-piece limited-edition necklace in pure 24kt gold featuring all 12 animals of the Zodiac, signed by the artist and priced at £36,000. Alongside this collector’s edition necklace, Taschen also offers single, 24kt gold Zodiac medallions, each one limited to 99 pieces and strung on to red silk, for £2,950: an ‘entry-level’ offering in the world of artists’ jewellery.

Meanwhile, at London’s Frieze art fair, French jewellery house Dauphin unveiled a limited-edition series of rings and pendants in partnership with Serpentine Galleries. The ‘Nanomuseum’ range drew on the concept of a ‘portable museum’, conceived in the Nineties by the gallery’s artistic director Hans Ulrich Obrist and artist Hans-Peter Feldmann. Original artworks by Etel Adnan, Martino Gamper and Rachel Rose were transposed on to Dauphin’s signature ‘C’ ring and frame-like pendants, which are sold at avant-garde fashion emporium Dover Street Market (prices range from £600 to £4,140).

In New York last November, the Gagosian gallery unveiled a bejewelled ode to Man Ray by Eugenie Niarchos’s brand Venyx. Eleven limited-edition designs feature the artist’s surrealist eyes and lips in enamel or diamonds – a contemporary spin on the solid-gold jewels that Man Ray himself created in the Sixties with the help of his Italian jeweller friend GianCarlo Montebello. And in Aspen in December, Jessica McCormack launched her second collaboration with Californian artists the Haas Brothers: a collection of diamond- and pearl-encrusted mollusc-inspired jewels, a precious ode to the twin brothers’ latest sculpture exhibition, ‘Snails in Comparison’.

Wearable art

These new art-jewellery hybrids focus on wearability – which hasn’t always been the case. Painters and sculptors generally ‘tend to be more interested in how the piece is conceived than how the wearer feels and how it looks’, says Louisa Guinness. ‘Artists want to create a statement, an artwork in itself – they rarely make compromises.’

[See also: Is the superyacht industry sailing too close to the wind?]

Her previous collaborations include an 18kt white gold bookmark stamped ‘HERE’, conceived by Ed Ruscha; a chain strung with a miniature replica of HMS Victory in a glass bottle, by Yinka Shonibare; and 10cm-long earrings made from laser-sintered polyamide by Ron Arad. Having recently relocated her gallery to Kensington, Guinness now exhibits work by contemporary jewellery designers such as Silvia Furmanovich, Hannah Martin, Alice Cicolini and Emefa Cole alongside her artists’ jewels. She considers these designers ‘artists whose medium is jewellery’.

Clients’ interest in the crossover between art and jewellery, Guinness believes, is driven by ‘a desire for individuality and originality. People increasingly want to make a bold statement. Artists are good at pushing the boundaries – they are more courageous, a little less conservative. That’s what makes their work so interesting and collectible.’

This feature was first published in Spear’s Magazine Issue 90. Click here to subscribe