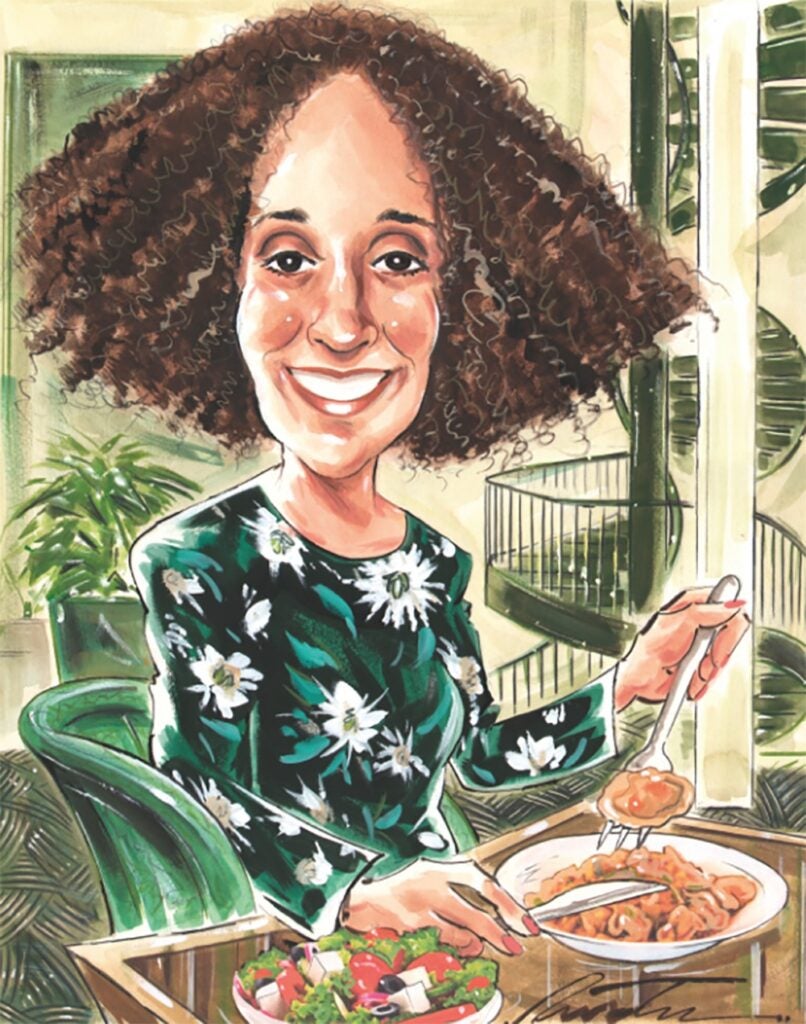

I first catch sight of Katharine Birbalsingh through a set of ornate gold railings on the window near the entrance of the Guardsman Hotel at St James’s Park.

She is dressed in a flowing blue frock with floral patterning and looks somewhat perplexed. She has only tentatively approached the front door so I frantically wave in her direction.

Birbalsingh is relaxed and jovial as we settle down in the Guardsman’s dining room. Socially speaking, she has ‘quite a boring life’, she says.

Her schedule as head of both a Wembley free school and the government’s Social Mobility Commission is usually marked by a sense of urgency, and not the laid-back rhythms of a Liquid Lunch with Spear’s.

But today is the penultimate day of the summer school term, so Birbalsingh has been able to sneak away from a school trip to the Natural History Museum.

‘I’m not sure I ever really switch off – I live and breathe this stuff,’ she says, leafing through the copy of the Spear’s Schools Index I’ve handed her.

Assessing its rankings of top private schools quickly takes priority over the task of selecting a starter. ‘It sounds silly for me to say, “Well actually, I think we can compete with [the top private schools],” but I do think that… and, in many ways, I think we’re better than them.’

By ‘we’, Birbalsingh means Michaela Community School in Wembley, the diverse free school she founded in 2014 which serves some of London’s most deprived students. Its humble setting is something of a contrast to the images of leafy boarding schools she’s perusing.

‘We’re by a train track in an old office block, with no grass and no trees and no fields, and no sports hall. And we cannot offer the variety of subjects. I get £4,500 per year per child, these schools get over £30,000,’ she says.

‘But I would say there’s a lot more to a school than the number of subjects you offer and the grounds.’

For one thing, ‘I know that their discipline isn’t as good as ours,’ Birbalsingh affirms, diving into the no-nonsense pedagogical practices that have earned her the sobriquet ‘Britain’s strictest headmistress’.

Her 750 pupils process through corridors in silence, study a demanding curriculum and, famously, face the threat of detention for forgetting a pen.

The tough script on discipline must be shared by all staff. When recruiting, Birbalsingh attempts to find out whether new teachers would ‘wince at the pen thing’.

You must give the detention or the child will never learn to bring the pen in. You confine that child to the limits of your low expectations.

Give the detention and next time, they will bring in the pen.

Children will adapt to the expectations around them. They have agency. https://t.co/U2XIM0oMW7

— Katharine Birbalsingh (@Miss_Snuffy) January 11, 2020

We have the full attention of our charming waiter, who points out that the quiet dining room is usually reserved only for hotel guests and residents – they are happy to make an exception for Spear’s and Britain’s most famous teacher, however.

Birbalsingh opts for tortellini to start, followed by gnocchi with a garden salad. I go for shallots and smoked salmon followed by a plump duck confit – oh, and a glass of Chardonnay. My guest abstains, noting that she will have to return to school later in the afternoon.

She pauses for a moment. ‘Now, it’s possible that your readers will think, “But we don’t want your type of discipline”… but I do think high standards of discipline mean that you get more of the child.

‘Of course, my dedication is to the disadvantaged, so that’s why I work in the inner city. And it’s particularly important to them, because the children of your readers… they could choose any of [the schools in the Spear’s Schools Index] and their child would be fine, right?!

‘What’s interesting is that your readers will agonise over documents like this,’ Birbalsingh laughs. ‘But I do think they’d get something really unique if they sent their child to us.’

The approach, she believes, instils good habits, a sense of ‘personal responsibility’ and ‘ownership over their own lives, so that when obstacles come, they don’t blame others’.

‘We feel it’s impossible to feel sorry for someone who is privileged’

Yet Birbalsingh is not against the most vaunted private schools, and certainly doesn’t think they should be abolished. ‘I would never want the state to interfere on that. I don’t believe in state interference,’ she says with a clipped certainty, pointing to the low percentage of students in the private sector nationally.

‘People always go on as if that’s the thing that matters. It’s 7 per cent. Who cares?’

The vast majority of wealthy students she’s encountered are ‘hard-working and decent’, and she finds it upsetting when their achievements are dismissed because of their advantageous starts in life.

‘Yes, in part, it’s because they have lots of support. But for the most part it’s because they worked hard… they’ve been up late at night studying,’ she says. ‘And what’s odd, in 2022, is that we feel it’s impossible to feel sorry for someone who is privileged, as if to suggest that simply because you are rich life is therefore always easy.’

But Birbalsingh does remember some of the raucous antics of her privately educated contemporaries at Oxford.

Her father was from Guyana (and made his own ‘huge leap’ in social mobility), while Birbalsingh herself was born in New Zealand and spent most of her childhood in Canada.

As a state school student at university in the 1990s, she says she sometimes felt out of place.

‘There were some idiots who used to go round drinking gin out of a shoe, and all sorts of ridiculousness!’

Amid the class divides she recognised, she dabbled in ‘lefty’ politics and read Marxist literature.

‘Like any student, you know, leftism seemed to be the way of pursuing justice for the poor. Life has taught me that that was wrong. And that, actually, “small c” conservative values are what will bring justice for the poor.’

The Michaela free school was opened a few years after her famous 2010 address at the Conservative Party Conference, where her pronouncements that the British state education system was ‘broken’, kept ‘poor children poor’ and expected the ‘very least from our poorest and most disadvantaged’ were greeted with a standing ovation.

Although the speech enhanced her profile, it also led to her departure from the south London school she worked for at the time. ‘I was in a position where I had to resign, and then I was told I would never work in the state sector again.’

It was also the first time her comments had attracted intense media scrutiny, which is now a frequent occurrence for Birbalsingh. Often vociferous criticism comes from ‘the people with power, the media classes’, she says, who might abhor her tough-love approach but seldom offer solutions to help her students.

‘The stuff that really makes me angry’, she says, is when ethnic minorities or disadvantaged children are let down by the ‘soft bigotry of low expectations’, and when well-meaning teachers tell them ‘“this piece of homework is very nice, darling”, even though it’s terrible’.

Since its opening, the school has gone from strength to strength. It was rated ‘outstanding’ by Ofsted in every category at its last inspection, and more than half of GCSE grades awarded to pupils in 2019 were at grade 7 (‘A’) or above. Its success saw Birbalsingh obtain a CBE in the Queen’s 2020 birthday honours. In 2024 a sister school will open in Stevenage.

Her ‘pull yourselves up by the bootstraps’ philosophy was recently given further validation: at the end of 2021 she was appointed head of the Social Mobility Commission, and in the role she has a wider opportunity to extol the virtues of ‘personal responsibility’ for the benefit of children everywhere.

So how does she aim to advance social mobility in her role? ‘You know, if we can improve the quality of teaching and the quality of the discipline, those two big things… we will see more of social mobility, that will just happen automatically.’

Her commission is also interested in the role of families who often ‘don’t know what they need to do – they don’t realise that giving their toddler a phone will stop them reading’.

Whether they send their children to leading private schools or struggling state schools, Birbalsingh reckons all parents can benefit from her advice.

She believes creativity only comes from a place of stability.

‘Thinking outside the box does not come out of chaos. It’s when a child is in order and structure and an environment which is more predictable that they then feel comfortable enough to think outside the box and be creative. That’s a paradox that many people don’t understand’.

Secondly, she says that when children are underperforming, parents might not realise ‘just how much the school may be responsible for that’.

Tutors, meanwhile, should be used as soon as possible for secondary school children who are falling behind and parents should never assume that just because a school is excellent overall, all the teaching will be.

‘Studies have shown there is much more in-house variation within one school than there is between schools.’

Before the table is cleared I ask about the Tory leadership contest going on at the time, but Birbalsingh deftly bats away any suggestion she had a preferred candidate in the race.

She has an inside track on Tory politics, of course: she personally knows Kemi Badenoch and Suella Braverman, the latter of whom served as her school’s first chair of governors, and she came into contact with Liz Truss through her social mobility work.

She’s also coy about Boris Johnson’s defenestration (he once came to visit her school when he was mayor of London).

‘I just say his hair’s a mess, his shirt’s untucked, you know, he needs to sort himself out! But look, people loved Boris, so he obviously had something.’

Two hours have flown by, and Birbalsingh must ‘get back to school ASAP’. Her kids will soon be returning from their museum trip.

‘They’re going to say, “Where on earth is our headmistress?” And I‘ll say I’ve gone for Liquid Lunch, and they’ll say, “What?!”’

She laughs again and heads off for the tube, back to Wembley.

Main image of Katharine Birbalsingh: Getty

More from Spear’s

The most expensive private schools in Europe

Do super-rich graduates value their universities?

Dean Forbes: Homeless to €1bn CEO