Some of you will have seen my exultant LinkedIn post after I picked up my first Italian passport.

I find it hard to explain why it was so important to me to reclaim the Italian citizenship that both my grandmother and mother were forced to renounce when they married Dutch and British citizens. For me, being Italian is about a sense of place and belonging. Emotional connection aside, the benefits of free movement in Europe are also undeniably attractive.

My own experience (perhaps ‘odyssey’ would be a better description, given how long and challenging it proved to be) prompted me to think about how the value and meaning of citizenship has changed for families.

[See also: Ireland tops rankings of best citizenships for HNWs]

A marketable commodity

Citizenship is traditionally seen as a right, acquired by birth or naturalisation, which reflects an individual’s identity and also comes with an expectation of loyalty.

It is, however, also increasingly seen as a marketable commodity. In times of peace and stability, the value of this commodity can appear diminished, but global conflicts, shifting governmental ideologies, growing authoritarian tendencies and changing tax regimes are prompting families the world over to apply a less emotive and more strategic lens.

When did the approach to citizenship start to change? Some scholars argue that globalisation, global mobility and migration, together with the increasing acceptance of dual citizenship by nation states, are key drivers.

In 1960, 62 per cent of countries in the world had a restrictive approach to dual citizenship, whereas by 2020, 76 per cent of countries had adopted a tolerant approach, according to data compiled by the Maastricht Centre for Citizenship, Migration and Development.

The extra-territorial reach of the tax systems of some countries such as the US is often cited as another contributor. Others point back to the mid-Eighties, when some Caribbean countries launched citizenship-by-investment (CBI) schemes in order to bring their ailing economies back to health.

Such programmes have become important economic drivers. Passports are now the largest export for St Kitts & Nevis, for example, and according to IMF data they amounted to 23 per cent of its GDP in 2023. Richer countries have also jumped on the bandwagon.

[See also: The best global mobility, residence and citizenship by investment advisers]

It may well be true that once nation states start making citizenship more about money and less about connection, they debase its real value.

If you sell your citizenships, you can’t demand loyalty in the same way. The notion of belonging to a country, which in exchange for guaranteeing certain rights and protections can, in the words of Hegel, expect ‘a readiness for sacrifice in the service of the state,’ is completely undermined.

If anyone has any doubt that acquiring citizenship has become a marketplace, I would suggest a quick scout of the internet. You will be offered, among other opportunities, a time-bound discounted citizenship of Vanuatu for US$105,000 and Turkish citizenship in four months for a $400,000 investment in real estate.

There are 12 countries offering CBI, according to the 2024 CBI Index report, two of which are in the BU: Austria and Malta. If you extend this to the countries offering residency schemes, it brings the total to 23.

[See also: Singapore reclaims top spot on the Henley Passport Index as UK slips again]

Global mobility scores

Various indices rank the most valuable citizenships, using factors such as visa-free travel, taxation, personal freedoms and global reputation. Reassuringly for me, Italy and the UK both have high global mobility scores, but I’m not very diversified by geography or by political regime.

Andrew Henderson, founder of offshore consulting firm Nomad Capitalist, recommends asking yourself what your objectives are in adding an additional citizenship and suggests applying the principles of diversification to building your passport portfolio, considering geography, culture and lifestyle.

I would add to this shopping list consideration of succession laws, tax regimes, quality of healthcare, financial systems and educational options as important selection criteria. You may not want to consider a country with forced heirship rules or one that is considering moving to taxation by citizenship.

[See also: The FIG regime: A Labour olive branch to non-doms?]

What is the optimal number of passports, you may ask? Experts tend to suggest a minimum of three passports to ensure that you remain in control of your own destiny and keep your options open, although some families have gone as far as eight.

In 2024, the world experienced the highest number of countries engaged in conflict since World War II. There are currently 56 conflicts, according to the Global Peace Index. Multiple citizenships, particularly from countries that are seen to be more neutral than your own, can give you valuable backup options.

To twist the words of J.F. Kennedy, perhaps we should be asking what these countries can do for us, when so many are increasingly demanding of what we can do for them.

Annamaria Koerling is managing partner of Delfin Private Office

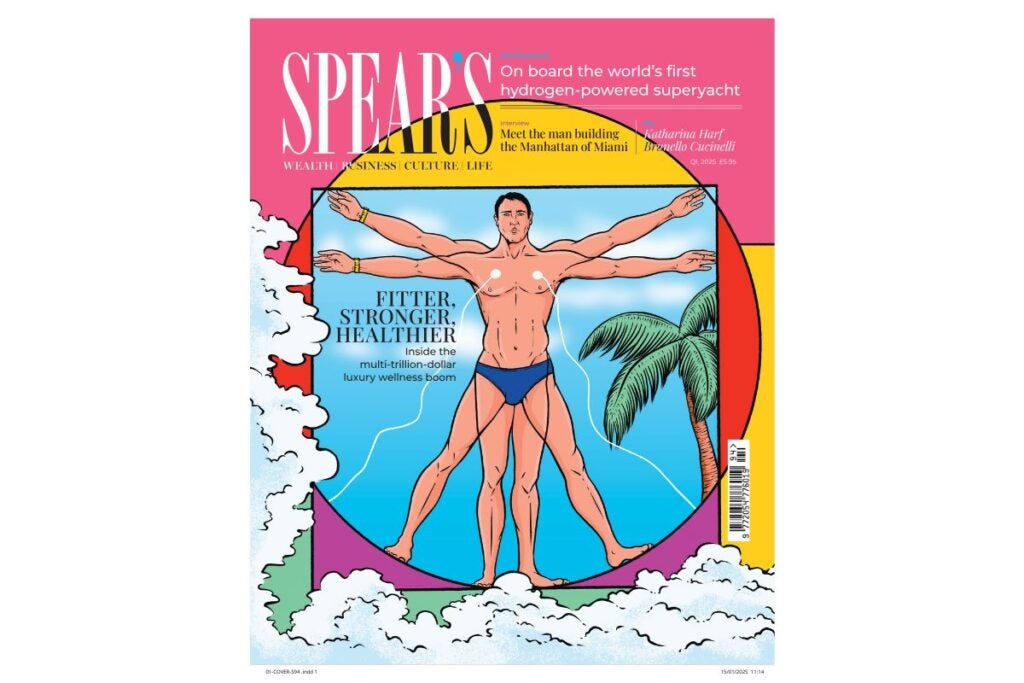

This feature first appeared in Spear’s Magazine Issue 94. Click here to subscribe