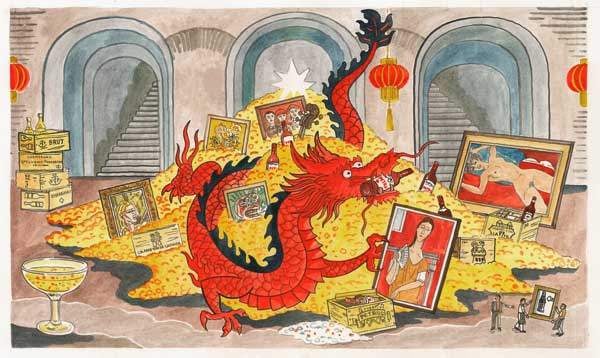

Chinese buyers have shaken up alternative asset markets, from wine’s ‘Bordeaux bubble’ to record auction prices for artworks. Olenka Hamilton examines what the dragon will do next

‘China is big,’ says Tom Harrow, co-founder of online wine marketplace Honest Grapes, which sells a wide range of fine wines and organises luxury wine experiences for HNWs around the world. He’s talking about the Eastern behemoth’s presence in and impact on the international wine market. China is expected to overtake the UK and France to become the world’s second largest wine consumer (behind the US) by 2020, with an estimated overall turnover of $21.7 billion in that year. According to figures from Sotheby’s it has already overtaken the US at auction, last year buying 58 per cent of the value of wines sold at auction globally (down from a 70 per cent peak in 2011, when the market crashed because of ‘the Bordeaux bubble’, which China caused with its wine-buying spree between 2008 and 2011).

It’s no surprise when you consider that China’s GDP has grown from $900 billion in 1997 to $11.2 trillion, resulting from economic reforms and the acceptance of free-market principles. Today, China might well have the most billionaires in the world (depending on whose estimates you read). The Chinese got so overexcited in 2009, buying the very best wines, that they pushed prices for the most prized labels up to 20 times their 1982 levels. A single bottle of Château Lafite Rothschild 2010 was going for €900.

‘It was the new big thing, the new status symbol,’ says Harrow. ‘From a relatively standing start, that’s huge. They simply weren’t exposed to Western luxuries before; now they have the income they want to experience them, and wine is part of that.’

The feverish wine-buying really got going after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008, when US buying slowed, says Jamie Ritchie, global head of wine at Sotheby’s. ‘There was a transfer at the time from the US as the most price-sensitive in the market to China, and that’s the current business today,’ he says. ‘There’s been a huge price appreciation driven by mainland Chinese buying, and that goes through the secondary and the futures market.’

That China is taking market share away from European consumers is undeniable, says Harrow, recounting the story of a colleague struggling to get allocations for 2016 Bordeaux early this year. ‘As a winemaker you go where the money is, and while you want to be loyal to your clients, the new markets are very exciting and they’ll often pay top dollar.’

Although Chinese buyers are noticeably driving the wine investment market, they are not buying wine for investment. They are buying it to drink, enjoy and show off to friends. ‘Being able to drink great wine with your friends gives you face,’ says Jamie Graham, who runs Brunswick Fine Wines and has been buying, selling and drinking wine in Hong Kong since 1996 and in mainland China since 2000.

Graham says his best ever wine-drinking experiences have been in Hong Kong and China, because of the quality of the corks that are pulled there and the level of expertise and sophistication they have acquired as a result. He now goes to China to scope out the investment market because ‘there’s no investment market if people don’t pull corks’. He notes a shift in appetite among clients from Bordeaux to Burgundies and predicts that China will continue to push prices up as connoisseurship grows. ‘I talk about “dog years”,’ he explains. ‘What takes seven years in Europe takes one year in China. Everything moves much more quickly there.’

The same is true for the art market. According to the first Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report, China took the largest share of the auction market in global sales of art and antiques, accounting for 34 per cent of the world total by value. Buying art isn’t new to the Chinese, of course: they’ve been buying their own for more than 1,000 years. ‘The first thing Chinese people do when they get some surplus cash is buy a piece of Chinese art,’ explains Colin Sheaf, head of Asian art at Bonhams. ‘It’s absolutely in the Chinese DNA to collect their historical culture, more so than any other population on earth.’

Chinese HNWs have now taken to buying Western art with similar alacrity, and much like with wine they are learning fast. And because they are buying only the best, they are sending prices of certain blue-chip art soaring.

Jonathan Green, who runs London’s biggest privately owned gallery Richard Green, notes a particular interest in ‘high-profile paintings by high-profile names’, especially the Impressionists and the bigger names among the Old Masters. ‘As far as paintings are concerned, at the very high level of $5-10 million and above, the Chinese have a strong impact on the market,’ says Green. ‘I think there were very few buyers pre-2010 for European paintings, but now there are more and more Chinese collectors as the years progress.’

A prime example of such a buyer is the former Shanghai taxi driver turned investor Liu Yiqian, whose museums now house the largest private collection of art in China and who used his Amex in 2015 to buy a Modigliani for $170 million at Christie’s. The sale was overseen by Giovanna Bertazzoni, co-chairman of Christie’s Impressionist and Modern art department, who has been travelling to China six times a year for four years, where it holds auctions and runs education programmes. ‘We’re talking to incredibly sophisticated people and accomplished collectors, who have been collecting Chinese art for 10 to 15 years, who have opened museums, such as Liu Yiqian,’ says Bertazzoni.

The Chinese are drawn to the Impressionists, she says, because ‘the typical Impressionist illusive brush stroke, which was a radical innovation of the Impressionists, is mirrored in the depiction of landscapes and nature in Asian art, and it strikes a chord with them’. And because they’re starting out, they’re more enthusiastic and determined and are growing increasingly audacious at auction. In June, 35 per cent of Christie’s Impressionist and Modern sales saw Asian bidding, the highest proportion yet, with the second-highest selling lot at the June sale in London – Picasso’s portrait of Marie-Thérèse, Femme écrivant (1934) – going to a Chinese buyer for £34.9 million.

Olyvia Kwok is a former London gallerist from Hong Kong who now runs Willstone Management, an art investment management firm based in London. Educated in the UK since the age of 12 (she is a graduate of both mathematics and art history), she offers Chinese HNWs a unique inroad into the Western art market.

‘It’s all for show,’ she says, sitting on an armchair in her grand Mayfair offices. ‘Can a Chinese person really understand what Modigliani did in Paris in 1901, understand the great love and emotions he experienced? The Chinese find it hard to relate to that, so what they do is buy recognisable things for kudos. They call me up and say, “I want a name that everyone knows for a good deal.” That’s literally what they say. There’s a huge fascination with Western art as a status symbol. Rich Chinese people like to stick together and copy each other.’

Kwok recalls a dinner party in Beijing where the host casually handed over a multimillion-dollar painting after losing a game of poker. Blue-chip art is also often exchanged between friends. ‘They’ll swap art, pass it around,’ she says, ‘and they might calculate how much the painting is worth per square foot.’ Not that they are selling. ‘The Chinese don’t like to sell, they like to buy and hold on. It’s not for investment. They like to have a good deal – it’s a mentality thing that they want to pay less than the market price. The fundamental idea is that they must have a good deal.’

Things could be about to change, though, because of China’s ‘One Belt One Road’ (OBOR) initiative, a long-term development strategy which aims to boost its position in global affairs by creating a China-centred trading network, now in its first phase. Because the programme needs funding, the government is putting pressure on companies and HNWs to curtail their spending abroad.

The signs are already beginning to show, says Kwok, who has noticed a significant slowdown in the purchase of art in the £10 million-plus category. Marc Hendriks, global strategist at wealth management firm Sandaire, is realistic. ‘Prima facie, if there is no replacement for Chinese capital to acquire those alternative assets – and it’s hard to see where that will come from – that will at least stop prices rising.’

But it’s business as usual for Kwok, who is positive it’s a temporary blip. ‘Every country, when restructuring, takes three or four years to do so and China’s only in year two. Things will return to their normal flow again and there is still a lot of appetite out there,’ she insists. ‘Buying art is like having sex. When you’ve had it once you want to have it again.’

Kwok is working on some of the classic Chinese art enthusiasts who are looking at Western art. ‘A friend has a comprehensive collection of bronze Buddhas from pre-Tang dynasty. Could he, would he, buy a Picasso? Maybe.’

Although the Chinese are not yet involved in the classic car market, it’s only because of punitive taxes on imported luxury and collector cars, which could still change. Classic car consultant Alexander Lewis doesn’t rule it out. ‘Many people hope the rules will be relaxed and believe if they are, the next great leg up in the market would be fuelled by their buying, rather like the Bordeaux bubble a few years back,’ he says.

The impact of the OBOR initiative is impossible to predict at this point, says Hendriks: ‘There’s obviously some discretion or freedom available to people, especially those who already have money outside China. For new money they’ll be more circumspect, though, because of the need to reorganise their banking system and redirect that capital in the way that they feel is most appropriate. Some degree of caution may be warranted, and we’ll see.’

Ultimately, with more than 500 billionaires in China, most of whom will already have holdings abroad, it’s hard to imagine they won’t find a way around it. As Hendriks says, we’ll just have to wait and see, but it does seem as though they’re only just getting started.

Olenka Hamilton is staff writer at Spear’s