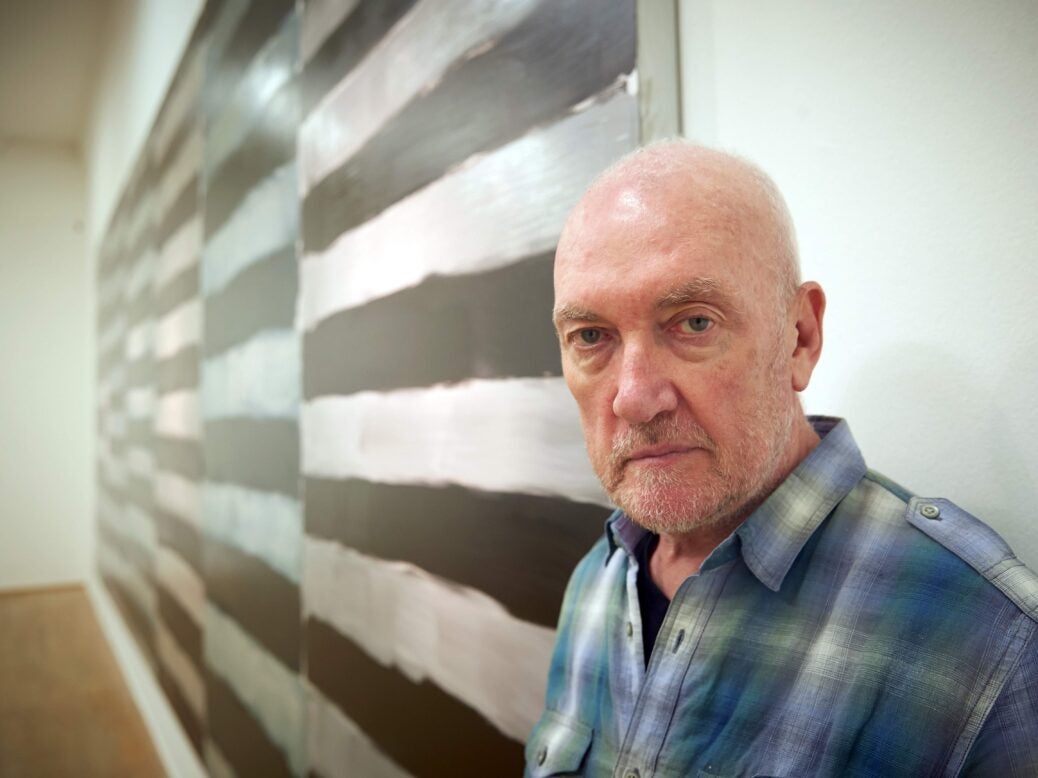

Sean Scully doesn’t shy away from pouring his eventful life into his abstract works. Just don’t expect to see them in corporate lobbies, writes Anthony Haden-Guest

The lives of artists are seldom page-turners, but that of Caravaggio is a good read, as is that of Gustave Courbet. And then there’s Sean Scully. Irish, raised in London, now a New Yorker, Scully began life with a vertiginous sequence of downs which fed into making him one of the best – and most successful – abstract artists in the world.

He was born in Dublin into a family of travellers. ‘It’s very important to me,’ he says. ‘The story of my grandmother’s journey across Ireland, begging, with her seven children, is all part of what I am. My grandfather hung himself in prison, because he was in the uprising of 1916. They were going to shoot him the next morning. On his death certificate they wrote, “Suicide from alcohol dementia.” They tried to take his death away from him. So there’s a deep wound in me. I can paint for 400 years with what’s burning inside me.’

The family moved to London when he was four. ‘We wanted to graduate into the working class,’ he says. He was happy in London. His father was a talented footballer. ‘He played for Arsenal juniors; he was two-footed. He could dance on both feet and shoot from both sides.’ He adds: ‘It was football as an art-form, like George Best. But he had to become

a barber for economic reasons.’

His mother sang vaudeville. ‘She would enter talent contests on the south coast and she always won. Her signature song was Unchained Melody. Bono sings that too.’ The rock star is now one of his collectors. As soon as his career took off, Scully bought his parents a house in Spain. ‘They became champion tango dancers,’ he says. ‘I have all the trophies. So my father didn’t die a frustrated man.’

Other experiences of a working-class Catholic childhood enriched his memory bank, such as making plaster casts from rubber moulds of the Virgin Mary and a rabbit and concocting scenarios around them. Or the imitation stained glass his grandmother would glue on to windows. (‘The interior light was extraordinary. Catholicism is a very visual religion,’ he says.) Or the services in a temporary church in Highbury, a shack with a tin roof. ‘When it rained it was fantastic. It was an avant-garde, Dada experience. Like John Cage.’

An art career seemed predetermined – but young Sean’s parents thought it shockingly marginal, like the life of a traveller, so he got jobs in printing and graphic design. But then he did apply to an art school. Then another, another, and another. ‘I was turned down by 11 art schools,’ he says, running through a list which includes Goldsmiths, future hatchery of the YBAs. ‘Then I was accepted by Croydon. It was a miracle.’

He worked ferociously, emerging as a hippy activist and a figurative drawer with portraiture skills. But he went to Morocco in 1967 and upon his return to London he began painting stripes. His career went as his parents had feared for years until 1974. ‘Not one person came to my studio. Not one,’ he says. He moved to New York. ‘And people ask why I left? Uhhhhh!’ A horror movie groan.

Manhattan can present itself as a grid of horizontals and perpendiculars. ‘I became unbound,’ Scully says. ‘I’d been strapped in, and when I came here the strapping came off. The discipline remained, but I wasn’t strapped in any more. Then I went to Boston and got a fellowship to Harvard. A bloody miracle, but I got it! Wow! There I was, this boy born on the streets of Dublin. And here I am at Harvard!’ He gives a ripe laugh, literally ‘HAHAHA’!

‘There was a building, the John Hancock Building, and the glass would fall out. [An] IM Pei [build]. And they kept replacing it with sheets of plywood. This is my painting! Because you’ve got glass, which is one kind of surface, replaced by plywood. And all these plywood patches were appearing on this immaculate glass tower. And that found its way into my work in the Eighties when I started putting in these inserts, this makeshift quality, this American kind of slapping-things-together quality.’ It was just what he needed.

‘I haven’t been included in a lot of group exhibitions that are based around cool geometry – and I have been happy to have been left out. My work has kind of got a knockabout quality. Some of my paintings look as if people have been living in them.’ He often works with Italian housepainters’ brushes: ‘They cost $12 and they last about three years.’

Mark Rothko observed: ‘There is no such thing as a good painting about nothing.’ Scully’s paintings are about something. He made several about the loss of his first son. One of them, Paul, is in the Tate. ‘When I got a house in London it was the first painting I made,’ he says, ‘because I felt closer to him where he died. The centre of it is in a sense ravaged. It turns in on itself. They are meant to convey powerful emotions, whereas a lot of abstraction tends to be decorative.

‘I was asked to make a painting for the lobby of Goldman Sachs and I just said no – I don’t allow my work to go into lobbies. I always thought that was a big mistake of Frank Stella. It demystified his work.’

As this indicates, Scully can pick and choose. He was, for instance, the first artist from the West to have a museum retrospective in China.

‘This guy asked me to do a show there,’ he says. ‘I couldn’t understand why. I learned I had a huge following there. They are very excited about abstraction. In China abstract painting was banned 25 years ago, because it’s highly charged with a spiritual agenda and it’s impossible to edit and control. So you either let it in or you don’t. And now they’ve let it in. Their language is highly visual and they have taken to it like ducks to water. So I had this show and it was successful on an unprecedented level.’

Further shows in China followed. ‘Which is funny,’ he says. ‘I’m born in Ireland and I have become this incredible cultural figure in China.’

He has no problem with questioning the work of his fellow abstractionists – such as Ad Reinhardt, who declared in the mid-Fifties, when he was making the all-black paintings for which he is famous: ‘I’m quite simply making the last paintings anyone can make.’

Scully’s response is simple: ‘You can’t just do what Ad Reinhardt did and expect people to follow you into the cellar,’ he says. ‘You go into the cellar and it’s black. And somebody says to you, “Isn’t it great?” Well, no. It’s great for like 30 seconds. But if you want to make something that’s an experience, that people get into and play with, you’ve got to give something.’

Scully wants his paintings to be – a word he likes – ‘usable’. Like Rothko’s. ‘Rothko connects himself to the history of romanticism,’ he says. ‘Seascapes, blurry horizon.’ The viewer can’t read Rothko’s mind, nor Scully’s, but they can feel the energy, get the mood, and they sure as hell know this canvas doesn’t belong in a hotel lobby.

Scully views his fellows on the high plateau and their multimillion-dollar projects with a cool eye. ‘I’ve always resisted the industrialisation of art,’ he says. ‘And those guys really embrace it. They start “fabricating”, as they call it, which is in fact manufacturing; they have intersected with money. But that is what Warren Buffett and people do. They do this money thing.’

He recalls meeting the Japanese über-artist, Takashi Murakami, in Hong Kong. ‘He was pleasant but he was kind of a clown, like Dalí,’ says Scully. ‘So these people are something between artists and TV personalities. I relate more to Bob Dylan, who is a popular figure and in some way controlled by the charts but has always maintained integrity in relation to it. And it’s all about being hand-made. My big concern is what you are putting into the world. In other words I’m not trying to make top-ten hits all the time. It’s really a body of work. Usable work.’