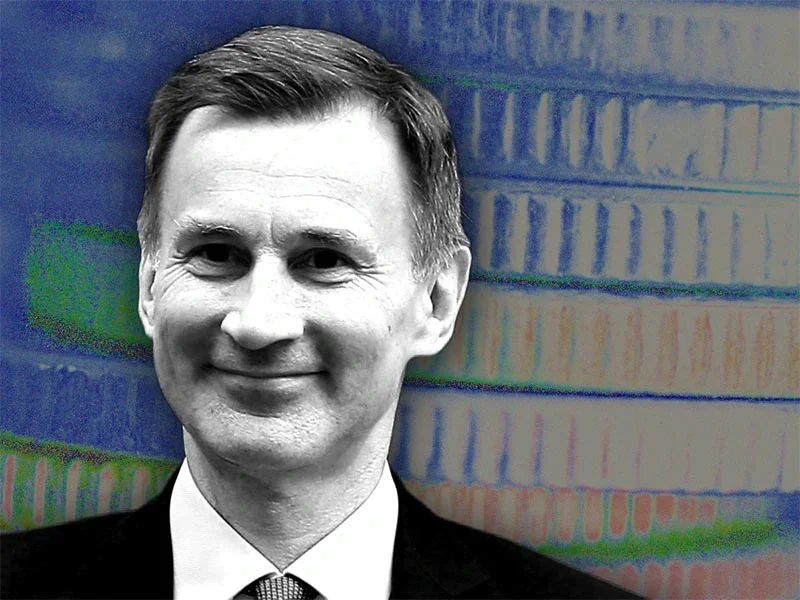

The Spring Budget 2023 is a case of stealth vs wealth as Jeremy Hunt uses fiscal drag to bring in more money, writes Mike Hodges, tax partner at Saffery Champness

Budgets are always the set piece moments for Chancellors to put on a bit of a show, but they generally come in two categories: ‘razzle dazzle’ or ‘steady as she goes’.

The kind of budget on the cards usually depends on where we are in an election cycle, with governments keen to save up their giveaways for when the public is starting to think about polling day, and to get unpopular policies out of the way early on in an electoral mandate.

For an example of the former, and bucking the electoral cycle trend, look no further than last year’s mini-Budget. Delivered by Kwasi Kwarteng in September, it was reversed almost in its entirety the following month by his replacement, the current Chancellor Jeremy Hunt, following intense backlash from the markets.

After such uncertainty, it was perhaps a foregone conclusion that Hunt would stick to steady as she goes for his first proper Budget. His hope will be that this reinforces his reputation as a safe pair of hands, willing to take difficult decisions on the economy for the sake of balancing the books. These include deferring the gratification of tax giveaways until we are at least in sight of the next General Election, and helping to restore the Conservatives’ desire to be recognised for fiscal prudence following the recent £30 billion budget windfall.

However, steady as she goes does not always mean plain sailing – at least as far as the taxpayer is concerned, especially if the good ship United Kingdom was already heading towards choppier fiscal waters.

Fiscal drag: Jeremy Hunt’s stealth tactic

Budgets can be defined as much by what they don’t include as what they do. In this year’s Budget there was nothing at all to address the effects of fiscal drag on people’s tax liabilities, which has continued to gather pace in line with inflationary pressures.

Fiscal drag is the phenomenon that allows the Treasury to collect more taxes by the chancellor doing absolutely nothing. Giving it a bit more context, when tax thresholds and allowances do not increase in line with inflation but wages do, taxpayers end up paying more year-on-year without the chancellor actually increasing headline tax rates.

When tax thresholds or bands (e.g. the higher and additional rate bands for Income Tax) and tax-free allowances (e.g. the personal allowance for Income Tax or CGT annual exemption) do not rise in line with either inflation and income growth, more income or gains become liable for tax or get taxed at a higher rate, and more people can get ‘dragged’ into higher rate bands.

Three ways tax burden has increased

Worse than simply allowing things to drag, the Chancellor has actively added to the tax burden. Firstly, in November, when he was in somber righting-the-ship mode, the Chancellor announced that the additional rate income tax threshold would be reduced from £150,000 to £125,140 from April this year, after which the thresholds and allowances for income tax, NIC and inheritance tax will be frozen until 2028. On top of this, the allowances for CGT and dividends will be halved from April, and halved again in April 2024.

Here, the chancellor has followed the course charted by his recent predecessor and now boss, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, who originally froze the income tax thresholds back in 2021.

Pressing ahead with the lowered additional 45 per cent rate income tax threshold, then maintaining it at the same level for another five years, will cause pain for an increased number of higher-income taxpayers. When you factor in the phased reduction of the personal allowance which begins when income reaches £100,000, the marginal tax rate up to a taxable income figure of £125,139 will be at an effective rate of 60 per cent.

Inheritance tax is another stark example of fiscal drag – arguably the starkest. The threshold for IHT, the nil-rate band, has been set at £325,000 since 2009, and the chancellor has committed to keep it at this level until 2028.

For a sense of how asset values have risen in this time, the average house price in the South East in 2009 was £212,000. At the end of 2022 it was over £400,000 – an increase of over 90 per cent. It is no wonder that the amount raised through IHT has increased from £2.3 billion in 2009 to £6 billion in 2021.

This is partly offset by the additional residence nil rate band, but this is a complex beast compared with the simple, but perhaps politically too controversial, solution of increasing the nil rate band to £1 million.

Not all bad news for higher earners

The Chancellor did, though, make one important concession to wealthier taxpayers facing up to larger tax liabilities, which will be particularly significant in the context of IHT.

By scrapping the lifetime allowance (LTA), which capped the amount that workers could benefit from in tax relief on their pensions savings to £1,073,100 across their lifetime, the Chancellor is – he hopes – incentivising wealthier individuals to continue to work, earn, and add to their retirement savings.

What’s more, with the annual allowance raised from £40,000 to £60,000, savers can now put more of their income each year into pensions before incurring punitive tax charges. With pensions savings usually outside the scope of IHT, this will allow people to pass on significantly larger amounts of wealth through their pensions without triggering additional tax charges.

There is, though, a counter view that this change may simply encourage people with large pension pots to retire now, rather than run the risk of a new Labour government reversing the change as Keir Starmer has already said he will.

When it comes to tax, retirement, and succession planning, it pays to take a long-term view. However, potential political changes that are still some way down the road should not be the cause of inaction. Higher earners who are facing an increased tax burden with the lowering of the additional rate threshold may be able to mitigate the effects by making the most of the increase in the pensions annual allowance – saving prudently and tax effectively.

Each individual will have their own set of circumstances and whenever there are sweeping changes to the tax regime, even those aimed at ‘simplification’, the best advice is nearly always to seek advice.

Mike Hodges is partner and head of the Private Wealth team at Saffery Champness

Order your copy of The Spear’s 500 2023 here.

Cover image / Shutterstock

More from Spear’s:

What the 2023 Budget means for high earners