It is 120 years since a Bavarian and his English brother-in-law took an office roughly halfway along Hatton Garden, the teeming artery to London’s jewellery trade, and started a watch company.

The pair, Hans Wilsdorf and Alfred Davis, imported Swiss watch parts, had them assembled in London and began selling them unbranded to local jewellers. They were good at it.

Getting early into the novel wristwatch fad, they were able to capitalise on wartime demand and found useful export markets in the sweltering reaches of the British Empire. In 1919, amid Britain’s struggling postwar economy, the company relocated to Geneva, and Wilsdorf, though a naturalised British citizen, moved with it, having bought Davis out.

[See also: Square watches are cornering the market]

By then ‘Wilsdorf & Davis’, the original trading name, had long since been dropped anyway, partly to avoid wartime antipathy to anything German-sounding. As Wilsdorf set up shop in Geneva, his firm was now well-established under a newer moniker: Rolex.

Poetic though it is that the definitive totem of Swiss exceptionalism started life as an Anglo-German importer and white labeller, it’s also fitting that its city of origin is now – as of March– home to the most colossal temple to the brand that you’ll find just about anywhere.

A marble-lined declaration of absolute supremacy

As watch shops go, the one at 34-36 Old Bond Street, a stately four-storey pile at the corner of Stafford Street (formerly home to Gucci), is less a retail space than a marble-lined declaration of absolute supremacy, in an area where prestige and brand power are still the only currencies that really count.

Connected by a staircase lined with grooved travertine (to mimic the famous Rolex bezel), there are concierges, hospitality spaces, a bar area and private consultation rooms where, depending on the heft the ‘V’ in your VIP status carries, you may get to try out the rare-as-hens’-teeth gem-set Rolexes that the store, almost uniquely, is stocking.

Downstairs, there’s also a space dedicated to the Crown’s ‘Certified Pre-Owned’ programme for the secondary market.

[See also: Strike gold with the new raft of bracelet watches]

Rolex, frankly, has things sewn up. According to figures published by Morgan Stanley in February, it accounts for more than 32 per cent of the global luxury watch market (for comparison, Apple’s share of the smartphone market is a bit over 28 per cent).

Besides slicing in on the pre-owned market, it’s also now directly in the retail game, having bought Bucherer, the world’s largest multi-brand watch chain. The Bond Street superstore, though, is owned and run by Watches of Switzerland, Bucherer’s biggest rival, which has had a Rolex shop on the street for more than half a century.

The old one amounted to around 900 square feet in space; the new place has almost 6,500 square feet of retail space, as well as extensive servicing workshops and more, making it the biggest Rolex monobrand store in Europe or America.

How’s that for inflation? As it happens, this palace to ‘the Crown’ has crashed down into a London watch retail landscape in a certain degree of flux. That end of Bond Street is crowded with watch brands, including Omega, Jaeger-LeCoultre, Richard Mille and Vacheron Constantin, all of which Rolex now dwarfs.

But the chess pieces have been moving around. Next door to Rolex, the shops of the high-prestige Richemont-owned brands, A Lange & Söhne and Roger Dubuis, have vanished, as has that of watch and jewellery specialist Piaget, replaced by a second store (the other is directly across the road, oddly) for its more profitable Richemont sibling, Van Cleef & Arpels.

Wempe, a super-deluxe retailer that stocked both Rolex and Patek Philippe further up the street, lost both those accounts and cleared off, while the mighty just get mightier: last year Patek Philippe, whose artful windows dominate Bond Street’s sprawling corner with Clifford Street, bulked up its stately salon rather dramatically by taking over the shop next door and expanding into it.

[See also: How Richard Mille became a watch industry juggernaut]

The cultural clout of luxury watches has never been higher.

Just look at the coverage of the Super Bowl (where Tom Brady’s $740,000 Jacob & Co Caviar Tourbillon was the standout) or the Oscars, not to mention Mark Zuckerberg’s strange pivot to ‘watch bro’ status (among a host of fascinatingly recherché pieces he’s suddenly begun sporting, he announced the scaling-back of Meta fact-checking in January while wearing a $1 million Greubel Forsey).

But the market is tough. The reasons aren’t complicated: discretionary spending is in freefall, a production glut during the post-pandemic boom years left a slowing market saturated, and inflationary forces (plus some thick dollops of pure greed during those boom years) have seen prices spiral.

As my colleague Rob Corder, editor of industry trade magazine WatchPro, told me: ‘What we’re seeing in real estate terms is the same thing as in the market: a huge market share grab by the biggest players, and everyone else just has to fit somewhere in between.’

Forget the idea of the ’boutique’

In fact, the entire nature of selling watches – at least at the very high end – is changing anyway. The old idea of sitting stiffly across a table from a sales rep and gingerly inching towards a purchase is giving way to something… well, a bit more jolly. Forget the idea of the ‘boutique’ – becoming the client of a top-tier brand these days can be more like joining a private members’ club.

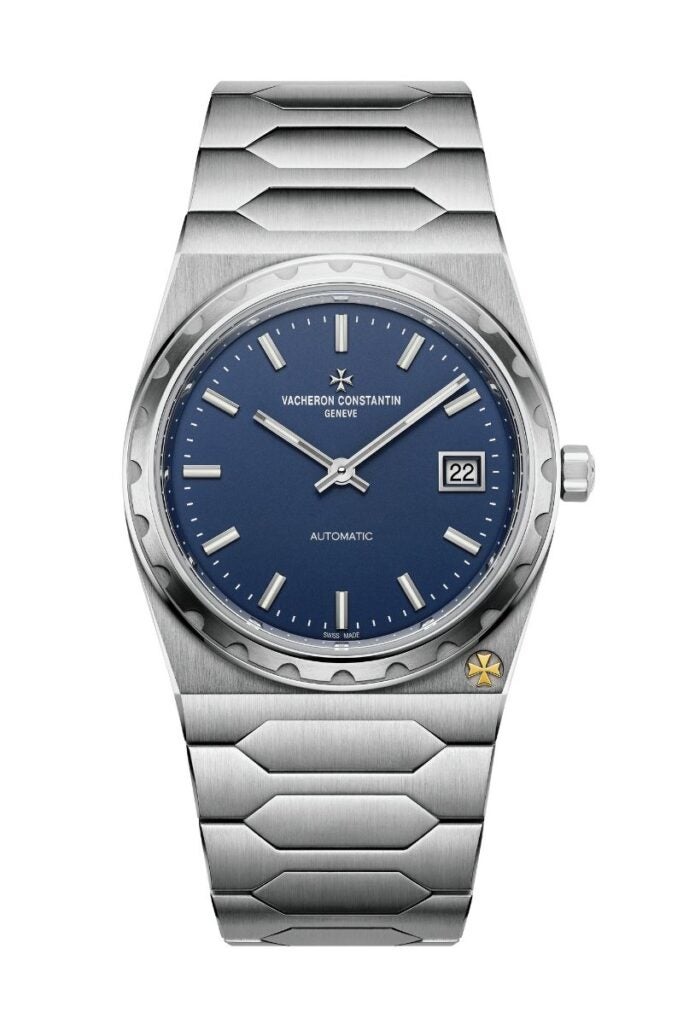

This is literally so in the case of Vacheron Constantin. Its dark little shop in a spot besides the new Rolex monolith has always underplayed the brand’s status as a member of fine watchmaking’s historic ‘holy trinity’ (alongside Patek Philippe and Audemars Piguet) but reflects the old view that any window space on Bond Street was better than no window space.

Now, though, Vacheron has roof space as well: via a secret entrance a few doors down, a lift takes you five floors up to Club 1755, a plush and airy penthouse environment with a cocktail bar, roof terrace and sensational views.

There are cigars and backgammon, private exhibitions for clients (sculptor Conrad Shawcross RA is artist in residence) and networking aplenty. This, says the brand’s UK manager, Charlotte Tanneur Teissier, is about ‘immersive engagement’. Existing clients will be on the invitation list, but store customers can get taken up to the space to view special watches in airier environs.

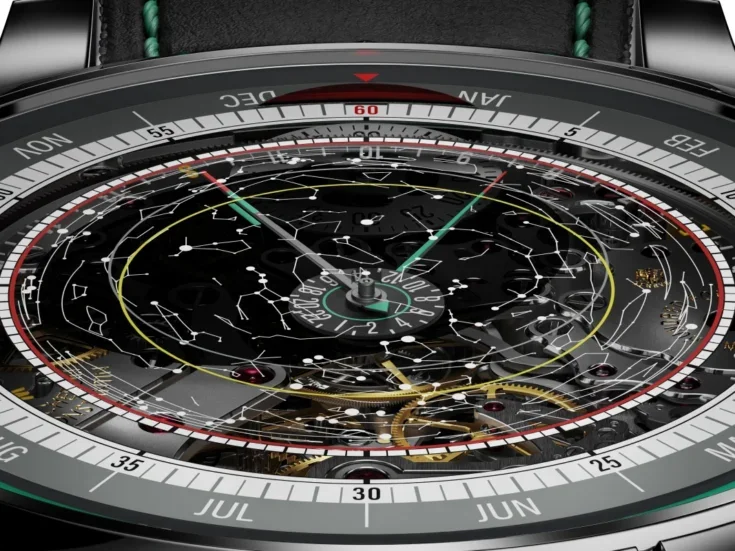

The brand, which turns 270 this year, was unveiling its latest collector must-have, an all-steel version of its classic 222 sports watch, when I popped in: private appointments, workshops, educational sessions and collector gatherings were scheduled just for this watch. Oh, and you can bring your old Vacheron in to be serviced by the brand’s master watchmaker, installed at a workbench by the window – the brand says it can service pieces going back to 1755.

Vacheron Constantin may be hanging on to its street-level boutique, but Bond Street windows seem no longer to be the statement-making necessity they once were. For that, there’s social media – and Mark Zuckerberg, of course.

[See also: Patek Philippe brings its Rare Handcrafts Exhibition to London]

A Lange & Söhne, the German maker that operates at the same price point as Vacheron but makes many fewer watches, has replaced its shop next door with a swish by-appointment-only lounge in Bourdon House, the private members’ club just north of Berkeley Square.

The trend-setter, though, is Audemars Piguet, which abandoned the traditional shop concept in 2019 when it opened ‘AP House’, a reception space/lounge/offices in a sweeping first floor apartment halfway up New Bond Street. It has a full-time chef, a huge cocktail bar and a regular programme of events for AP clients.

[See also: It’s time to give carbon fibre watches a second chance]

‘We’ve found that London as a city really lends itself to this format, since that world of private members’ clubs is really installed here,’ says AP’s UK general manager, Daniel Compton. ‘It’s very sociable, and people spend a lot longer here. We often have groups of separate appointments that end up as a general hangout, and that’s something we want to encourage.’

Such meet-ups, Compton says, have even resulted in customers going into business together. All-comers are welcome, and the brand keeps a full collection of watches on hand to show people. Though whether you’ll get your dream piece there and then – or at all – is a different matter.

[See also: Partners in time: the luxury watch collaborations worth knowing]

Waiting lists for most watches have fallen (along with resale prices) from the FOMO-fuelled highs of a couple of years ago. Nevertheless, there remain watches – and brands – where purchase histories and long-term loyalty are always the tickets to the most desirable pieces, rather than bank balances.

At Richard Mille, just about every watch is pre-assigned to customers before it leaves the factory. Although the brand has one of the larger Bond Street venues, only five or six watches are said to be kept in-store at any one time.

At FP Journe, the top-tier independent that opened a discreet shop on Bruton Street last year, there are watches to see but none to buy immediately. ‘We like to know where someone is in their knowledge journey, that they’ve done their research and have a real focus,’ says Shawn Mehta, the brand’s UK manager.

Since the company makes only around 1,000 watches a year, every piece has a waiting list – but at the shop, the brand’s community of collectors and clients come together for meet-ups, talks and gatherings over cocktails and canapés. First-timers are welcome, as long as they understand the journey. It’s not the depth of your wallet that makes the difference, but the extent of your commitment.

‘We’ll talk through the references, develop a wish-list with you, and then it’s a question of staying in touch,’ says Mehta. ‘Come to aperitifs, meet fellow collectors, join the conversation. It’s an organic trail where we open the door to you, and then it’s for you to see where you want to go down it.’

This feature first appeared in Spear’s Magazine Issue 95. Click here to subscribe.