What sort of a company would choose to stop making its most popular product? Patek Philippe president Thierry Stern tells Timothy Barber why he’s not afraid to make difficult decisions

In the world of luxury watches, the biggest story of the past year has centred not around a watch that launched, but one that vanished. Patek Philippe’s Nautilus 5711, its shapely steel sports model first introduced in 1976, has spent the past five years or so morphing from a wristwatch into an investment marvel, amid an accelerating blizzard of hype, speculation and opportunism.

It mattered not a bit that, at £27,000 brand new, the steel Nautilus was among Patek Philippe’s lowliest offerings; it was also one of its rarest and easily its most distinctive, with a glamorous all-rounder quality that made it a lodestar for casual luxury more widely. It was perfect Insta-bragging material.

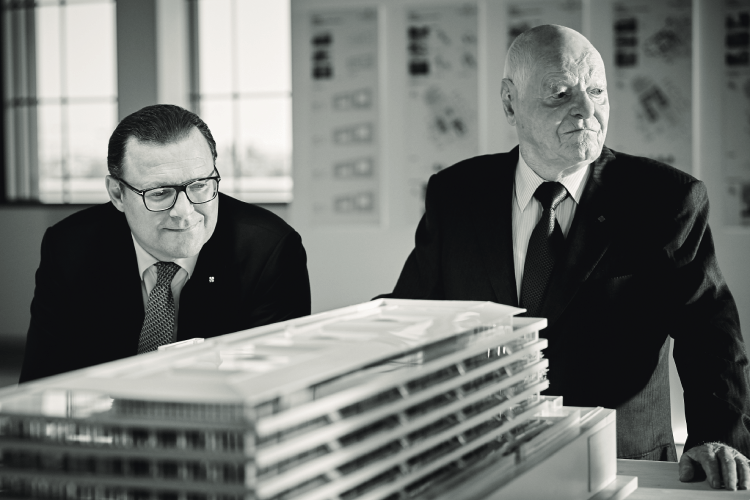

By early last year, waiting times for new models were reckoned to be more than a decade, while prices on the ballooning secondary market were speeding past £60,000. This was the point at which Patek Philippe’s president, Thierry Stern (pictured above left), pulled the plug. He announced – to the palpable shock of the watch industry and its commentators – that after 45 years, the steel Nautilus would be discontinued. It was like Porsche cancelling the 911. ‘We always said at Patek Philippe we are not going to be mono-product,’ Stern says when we sit down at Watches & Wonders, a huge trade show held in Geneva in late March.

There was plenty of speculation that Patek would be launching an updated replacement for the Nautilus, but Stern did not oblige. ‘It’s very dangerous to be defined by a single product, and it’s not what we like because our tradition is around creativity and innovation. There are so many Patek watches, and there’s so much we can do.’

Not least, Nautilus mania has come to represent a side of the market at odds with the heirloom status the brand’s slogan (you know the one) continues to project. Unlike almost every watch brand out there, Patek Philippe continues to rely on traditional, long-stand – ing retailers rather than opening many of its own boutiques (it has just three, in London, Geneva and Paris), placing its trust in the loyal relationships such stores build with their clients. But even those old-school loyalties were being tested against the prospect of a four-fold return on the instant flip of a Nautilus.

‘Sometimes it’s quite surprising to see that it’s the guy who has money, that we know has no difficulty really – he’s the one reselling the pieces. Not for the money, but just because he has it and he can do it,’ says Stern, who buys back several hundred watches a year on the secondary market to see where they’re coming from. I’m realistic. I know I cannot stop it and you have to live with it. That’s how it is when you’re successful.

While as a brand Patek Philippe may conduct itself with sepulchral seriousness and grandeur, the man at the heart of it is an affable and relaxed figure, who talks quickly and unguardedly – something of a contrast to the rehearsed polish found in a certain strain of Swiss watch biz professional. Back in the days of Basel – world, the long-standing (and now defunct) predecessor fair to Watches & Wonders, Stern would often be spotted standing out – side squeezing in a crafty cigarette between meetings. His tastes, he says, are down-to-earth. ‘When I go out, I go out with friends who are not maybe in my kind of position, not at all, actually. So we have beers, we have a meal, that’s it.’

My father would always tell me, finding somebody who has the DNA of the brand, the vision for it – there’s no school for that.

For Patek Philippe’s collectors, though, Stern is a lightning rod – the embodiment of the brand’s spirit, and the gatekeeper to its greatest treasures. ‘Thierry focuses on the human connection with his collector base. He travels constantly, listening, and engaging with the buyers that make the world of Patek Philippe,’ says John Reardon, a global authority on the brand and former auctioneer who deals in vintage Patek on his platform, Collectability.com. ‘He not only wants you to have the best watch, but he also wants his clients to have the best experience in buying the watch, servicing the watch, and keeping the watch for future generations.’

Not that Stern isn’t prepared to have some fun stirring the pot. After his announcement of the Nautilus’s cancellation, prices inevitably shot up still further, fuelled by a couple of ultra-limited final editions: a green dial version, and at the end of the year a Nautilus in partnership with Tiffany (newly acquired by LVMH), with a dial in lurid Tiffany blue. Only 170 of the latter have been made, with the likes of Leonardo DiCaprio, Jay-Z and LeBron James spotted wearing them – a kind of ultra-flex for the A-list.

Immediately, prices for watches from other brands with similarly coloured dials shot up too, while a single Tiffany Nautilus was auctioned for charity and fetched $6.5 million, a mere 120 times its retail price. Meanwhile, the ‘normal’ steel Nautilus had, by February this year, reached a market price of £160,000. Was Stern wary of being seen to pour oil on the fire?

‘Oh I knew it,’ he says with a twinkle. ‘The only advantage was this time it was Tiffany’s responsibility. We talked about it and they knew it would be popular, but I think they didn’t realise how difficult it would be. The whole world wanted it.

The Nautilus 5711 may have gone out in style, but killing off your marquee product at the peak of its popularity is a bold move for any company. According to Oliver Müller, principal of the Geneva-based industry monitor LuxConsult, it’s essential to understanding how Patek Philippe, owned and run by the Stern family for four generations, goes about its business. ‘No listed company would take the risk of removing the best-selling product – they’d be making more, finding ways to push it further,’ says Müller. ‘It’s very courageous, but also very logical in terms of the long-term way they think. They’re thinking in decades, not years. And with the money they’re earning, they can afford to take such steps.’ Indeed.

While Patek Philippe doesn’t publish its figures, the company is estimated by Morgan Stanley to have turned over at least CHF 1.5 billion last year (a figure Stern has said is an underestimation), and according to Bloomberg it could be worth $10 billion were it ever sold. Which, Stern says, it won’t be, despite oft-circling rumours that were only stoked by the Tiffany/LVMH partnership. ‘Why would I sell? Just to get money to be bored? As you can imagine, I’m not working for money today. The money – keep it for Patek.’

Stern, – who is estimated by Forbes to be worth more than $3 billion – admits that, at a certain point, the numbers become largely abstract anyway; his focus, he says, is relentlessly on the product, and the capabilities to produce ever better, more exquisite watches. Attend to that and, for Patek, the profits and legacy take care of themselves.

‘We don’t mind too much about the exact figures. We just know what we want to achieve and how we want to evolve,’ he says. ‘The figure that matters is the amount of watches – that’s what I care about. We know exactly any problems that we get in production, we know what the dial factory is doing, who’s making this or that component, which watches are for which market. This is what is important.’

To that end, in 2021 Patek Philippe opened a huge new factory at its premises in Geneva: a vast, £500 million ocean liner of a building, 200 metres long with five floors above ground and four below. It adds to the five other facilities Patek has dotted around Switzerland’s watch heartlands. It’s a remarkable footprint for a company that makes just 67,000 watches per year (Rolex, for comparison, makes more than 800,000).

‘I’ve kept some floors empty for the future, though we only ever increase at 1 or 2 per cent. It’s about making things more efficient and bringing as much under one roof, because I need the new technology but I also need the hand-made,’ Stern says. ‘If my grandfather had seen this, he’d be amazed – he’d say, “My God, we achieved it!” But he’d be thrilled that I still have the enamel guys, the engraving, the marquetry. He would be very proud that it’s not just a building that’s very efficient in an industrial sense, but we’re making art there still.’

In today’s watch industry, the vast majority of high-end brands are owned by luxury conglomerates like Richemont Group or LVMH, while Rolex is in the hands of a charitable trust. Only Chopard (much smaller) and Audemars Piguet remain family affairs, though the latter, arguably Patek’s main rival, is run by a professional CEO, with ownership shares split among the largely invisible descendants of its founders.

Patek Philippe, by comparison, is like a monarchy, with ruling responsibilities handed down from father to son. ‘Thierry Stern is the core of every major strategic, technical and commercial decision,’ says Reardon. He points to the ‘application process’ for acquiring one of the brand’s most sought-after complicated watches. ‘You want to buy a minute repeater from Patek Philippe? You need Thierry Stern’s personal blessing, and odds are you already had dinner with him a few times. Now that’s hands-on management.’

Now aged 52, Stern has been at the helm of Patek Philippe since 2009, when he took over from his father Philippe. The original family business, Stern Frères, was a supplier of high-quality dials to Patek Philippe; in 1932, when the watchmaker fell into difficulties following the 1929 stock market crash, the Sterns bought it and set about modernising, building up and expanding internationally, with extraordinary success. At the heart of decision-making today, says Stern, is a deep understanding of the company and its traditions that can only come from within, and a sense of long-term responsibility handed down, like both the watches and the knowledge to make them, from generation to generation.

‘My father would always tell me, finding somebody who has the DNA of the brand, the vision for it – there’s no school for that. You’re going to have to stick inside Patek Philippe, listen to the people and it’ll come day by day. That’s exactly what happened. And I’ve been travelling all my life, listening to customers, clients, experts, and all that is in my head. Then I try and mix all of that with the DNA of Patek Philippe.’

It’s in the conception and design of new watches that Stern is especially hands-on, leading three or four product development sessions every week. ‘I grew up learning creation first, then running a company,’ he says. ‘I choose the team, I choose the design, and I’m at the heart of it from start to finish. I’ve been doing that since I was 19 years old.’

It’s where he is most obviously leaving his mark on Patek Philippe. Under Stern, the Patek aesthetic – once delicately formal and understated – has become bolder and more vibrant. Or to use his term, ‘more aggressive’. He points to a new watch, a Calatrava (Patek’s line of classic dress watches), in which the sparkle and gleam of Patek watchmaking is paired with militaristic, vintage-chic details and a shadowy grey dial bearing a deeply stippled texture (see below). It’s a potent brew, with unusual inspiration.

‘I was with a friend with a vintage camera collection, and I noticed the material those old cameras are made from and thought, “Wow, it’s a nice look.” So that’s how we made the dial. It’s something more casual and active.’ But the Calatrava was never casual? ‘You have to evolve. I need, as the president of Patek Philippe and the head of creation, to take risks. Otherwise I’m useless.’

Now though, he does have help: his sons, aged 19 and 20, are themselves becoming involved, and contributed to the styling of the new watch. So succession is assured?

‘I never pushed them. I chose to go to Patek Philippe, my father never pushed me, and it’s the same for them: I will never oblige them. I told them, “If you’re willing to come and work with Patek, you will be more than welcome, but it has to come from you.” As soon as I said that, their grades went up directly. They were relieved: I know the pressure you feel on your shoulders when you see this as a kid. It’s a big responsibility.’

[Main Image courtesy of Patek Philippe