Hidden behind a mirror-panelled wall inside David Morris’s plush Bond Street boutique is a tiny, non-descript door. Most people would have to stoop to walk through it. This seems apt, because it leads to what feels like another dimension – one in which the decor is less opulent and the vibe less reverential, but which is the birthplace of the house’s most extraordinary creations. Four floors up, overlooking the bustle of Mayfair’s luxury artery, is the David Morris workshop, where 12 artisans beat, saw, hammer, set and polish pieces of high jewellery with price tags that reach seven figures.

[See also: Sky’s the limit for sustainable diamonds brand creating jewels out of thin air]

‘All the juicy stuff’

‘It’s difficult to put a precise number on how many pieces we produce per year, because a lot are sold before they even go into the boutique,’ says head of production Lucy Archibald, who project-manages the creation of these one-of-a-kind pieces. While the house’s fine jewellery is produced off-site, the craftspeople here create the 25 or so pieces that form each twice-yearly high jewellery collection, along with one-offs and special orders. ‘All the juicy stuff,’ as mounter Alan Pither puts it.

[See also: Dame Sarah Connolly on harnessing the persuasive power of the arts]

Pither has worked for David Morris for 26 years, since the boutique and workshop were based on nearby Conduit Street. The workshop moved to Bond Street in 2006, and the team has grown as the house focuses more on unique pieces, such as the recently completed necklace set pictured above. It has a 15.22-carat, D-colour, internally flawless marquise-shaped diamond and a 9.58-carat Paraiba tourmaline, and is the result of 600 hours of work by Alan, his son Lewis (who joined as a 17-year-old apprentice in 2014) and setter Paul Barfield, who’s been with the house for 36 years.

Precious Paraibas

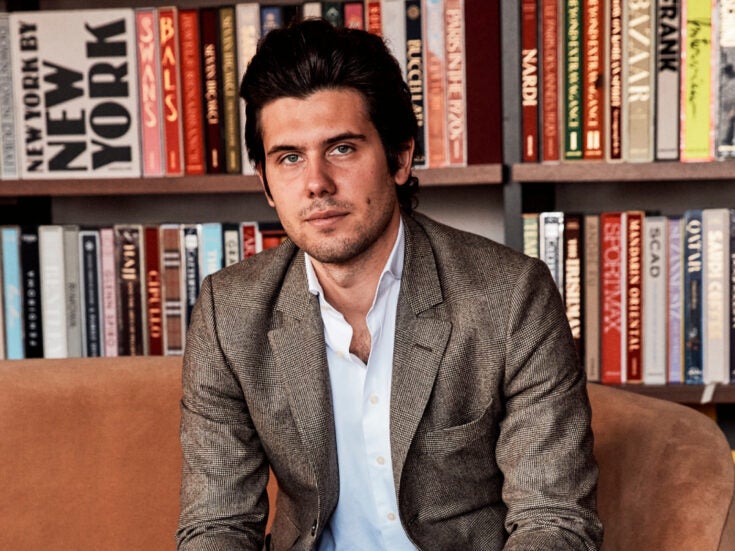

The necklace demonstrates managing director Jeremy Morris’s penchant for the more unusual corners of the coloured-gemstone world. Alongside the ‘big-four’ (diamonds, sapphires, emeralds and rubies), he also sources coloured diamonds, electric-hued Paraiba tourmalines, spinels in every shade and rare pearls from all over the world, often reusing gems from antique jewels.

‘I started working with Paraiba tourmalines more than 20 years ago when they first came out of Brazil – I was attracted to them as they offered a new colour palette to experiment with,’ says Morris, whose father, David Morris, founded his eponymous business in 1962. These stones have become a firm favourite with collectors, Morris believes, because ‘most of our clients already have all the other gemstones, while Paraibas are still fairly new and exciting’. The Paraiba at the centre of this latest necklace emits the hypnotic turquoise-blue hue of a Caribbean lagoon, its intense colour complemented by cobalt-blue Vietnamese spinels.

[See also: Best whisky advisers for collectors and connoisseurs in 2024]

The pleasingly plump tourmaline is surrounded by a halo of shield-shaped, pavé-set motifs, its chain punctuated by kite-shaped diamonds. Such striking geometry has become a signature of the house. ‘The combination of briolettes and unusual kite-shaped diamonds have both an Art Deco and Indian influence, giving this piece a casual elegance,’ adds Jeremy – although ‘casual’ is a subjective word for a necklace with a price that is revealed only upon application from serious buyers.

Keeping an old craft alive

For Alan, Lewis and the rest of the workshop team, astonishingly valuable gemstones are par for the course. ‘It’s kind of normal because I’ve been surrounded by it my whole life,’ says Lewis of the first time he laid eyes on a diamond the size of a domino. But being accustomed to something is not the same as being blasé. ‘You are definitely aware of the cost,’ says Alan. ‘We had some sapphires up here earlier that are being made into a necklace. The cost is $4.5 million, apparently. For seven sapphires. We take that very seriously.’

Those sapphires are destined to be set against a backdrop of pink and white diamonds; Lewis shows me the layout of diamonds, blu-tacked on to a gouache design. At his desk at the back of the workshop, he’s creating a CAD (computer-aided design) model of each diamond so that he can design individually sized collets. These will be 3D-printed in wax and assembled so that Jeremy can sign off the design, before production begins in solid gold.

[See also: The collaborations with artists breathing fresh life into the world of jewellery]

CAD and the casting of components from 3D-printed wax moulds make the crafting process more efficient, but not necessarily faster than handmaking from scratch. The workshop uses a combination of both approaches. ‘It’s more precise and you use less metal [with CAD], but somebody still has to spend the time creating it on a computer,’ says Alan. ‘Then we hand-polish and clean up each individual component, just like we do when they are handmade.’

Lucy adds: ‘Some houses will literally cast an entire piece of jewellery, which does make it faster and works for mass-produced collections, but here we make every element separately and finish it by hand to retain that elevated, handcrafted feel. Jeremy is always very keen that we make each section individually.’

When he’s not sourcing stones or hosting clients in Mykonos, Gstaad or St Moritz, Jeremy is a regular visitor to the workshop. ‘He’s like a kid with a new toy – “Is it ready yet? Can I see it?”’ says Paul, who hand-sets every diamond and gemstone, from microscopic diamond pavé to the shapely Paraiba in this necklace.

‘Most of the techniques I use can be traced back to the 1700s – it’s the same principle, it’s just the tools that have changed,’ he says. When the house invites clients into the atelier, they are spellbound by the work on each piece. ‘People still don’t realise what it takes to make jewellery like this. We start from scratch with a piece of wire, and we end up making these incredible necklaces and rings. We’re probably the last workshop in the West End that’s producing really big, fabulous pieces in-house.’ Paul gestures to the framed pictures of high jewellery that line the walls. ‘Everything you see, we’ve made here from start to finish.’

Working for a family-run house means a degree of nimbleness and flexibility that’s rare in larger, more corporate maisons. That’s not without its challenges – some designs might be changed halfway through production, for example – but Jeremy’s enthusiasm is clearly infectious. ‘I never set the same piece twice,’ says Paul. ‘I guess that’s why I’m still here after 36 years. It never gets boring.’

This column was first published in Spear’s magazine: Issue 91. Click here to subscribe