The Bonanza King: John Mackay and the Battle Over the Greatest Riches in the American West

by Gregory Crouch

Few people will have heard of John Mackay, and yet his story is every bit as fascinating as those of the first Astor or Vanderbilt. At the time of his death in 1902, newspapers estimated his fortune at somewhere between $50 million and $100 million. He never kept count and he never lost the perspective that came with his humble beginnings and hardscrabble working life. Admired for his integrity in his business dealings and his refusal to squeeze his employees’ wages, Mackay believed wholeheartedly in the virtues of honest sweat and toil.

‘Although Mackay stood among the leading industrialists and mining magnates in the last decades of the 19th century in terms of his wealth, none of the vitriol directed at the “Robber Barons” of the age had accrued to him,’ writes Gregory Crouch.

And although Mackay gave frequently to charitable endeavours, he endowed no eponymous foundation to burnish his name beyond death. Mackay was born near Dublin in 1831, in a cottage shared with the family pig. His family crossed the Atlantic in 1840 and settled in the slums of Lower Manhattan.

When his father died, the 11-year-old Mackay left school to work as a newsboy in support of his mother and sister, subsequently becoming an apprentice ship’s carpenter. Having read about the California Gold Rush of 1849, he earned his passage to the Pacific coast, arriving there in 1851, and spent his first few years panning for gold in the riverbeds of the Sierra foothills. In 1859 he arrived at the Washoe Diggings in western Utah Territory (later Nevada), where two communities, Gold Hill and Virginia City, had been established on the slopes of Mount Davidson. Numerous mines yielded ore that was rich in both gold and silver; some mines proved worthless.

Mackay laboured as a common miner in this early phase of excavating what came to be known as the Comstock Lode, during which shares in mines were frequently traded, with ‘sharpers’ from San Francisco spreading false rumours before dumping worthless stock on the unsuspecting. Over the next 20 years, the miners had to contend with freezing winters, droughts, an Indian war, and the distant American Civil War – the US government desperately needed bullion from the Comstock to help underwrite President Lincoln’s new paper currency, known as ‘greenbacks’.

Crouch writes lucidly about the technicalities of mining operations, and his accounts of underground fires are vivid and frightful. He also places Mackay’s heroic story in the context of the business chicanery that he encountered. Self-taught, resilient and taciturn, he was fair-minded where others were rapacious. The Comstock Lode was not just a bonanza for miners, it was also one for speculators and lawyers: ‘Comstock mining claims generated lawsuits like the barrels of the army’s experimental hand-cranked Gatling guns spewed out bullets.’ Of course, there were genuine lawsuits disputing titles to mining claims, but many were opportunistic bids, so-called ‘vampire suits’. Even genuine disputes could drag on for years.

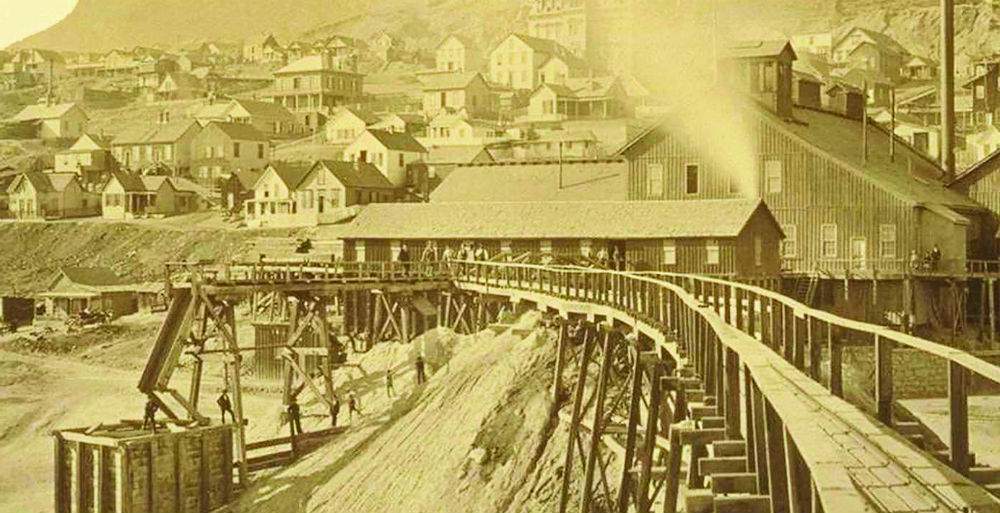

The extraordinary dimensions of the Comstock ore bodies meant that the mines consumed vast quantities of timber for reinforcement, as well as requiring efficient mills to extract the precious metals and cost-effective transportation to market – which was where ‘the Bank Ring’ came in.

A San Francisco-based real estate and mining investor, William Sharon, his ex-cashier partner William Ralston, and others, formed the Bank of California, which lent capital to mines in return for shares and voting proxies.

They did the same for milling operations. Then they used their control of the mines’ output to put pressure on the mill owners. Before long they controlled some of the most lucrative mines, most of the mills, even the supply of water and timber, and their crowning achievement, the Virginia & Truckee Railroad. The Bank Ring was nonetheless bested a few times. First, when Mackay and partners launched a corporate raid on the Hale & Norcross mine, catching the Ring unawares. Second, when John Percival Jones snatched the Crown Point mine away from them.

And finally, when Mackay’s Consolidated Virginia strike in 1872 made him the unassailable ‘bonanza king’. Meanwhile, the Bank of California had overextended itself through Ralston’s indiscriminate lending. The Comstock Lode generated around $306 million (or $545 billion in today’s terms). The San Francisco Stock Exchange and banks grew largely on the back of the Comstock.