From its journey from pocket to wrist, to the rise of electric movements and a mechanical renaissance, former Sotheby’s horology expert Alexander Barter charts the 20th century evolution of the watch

The story of the watch in the 20th century is largely defined by its evolution from the pocket to the wrist. The tide began to turn during the First World War, but it was not until 1934 that exports of wristwatches from Switzerland exceeded those of pocket watches.

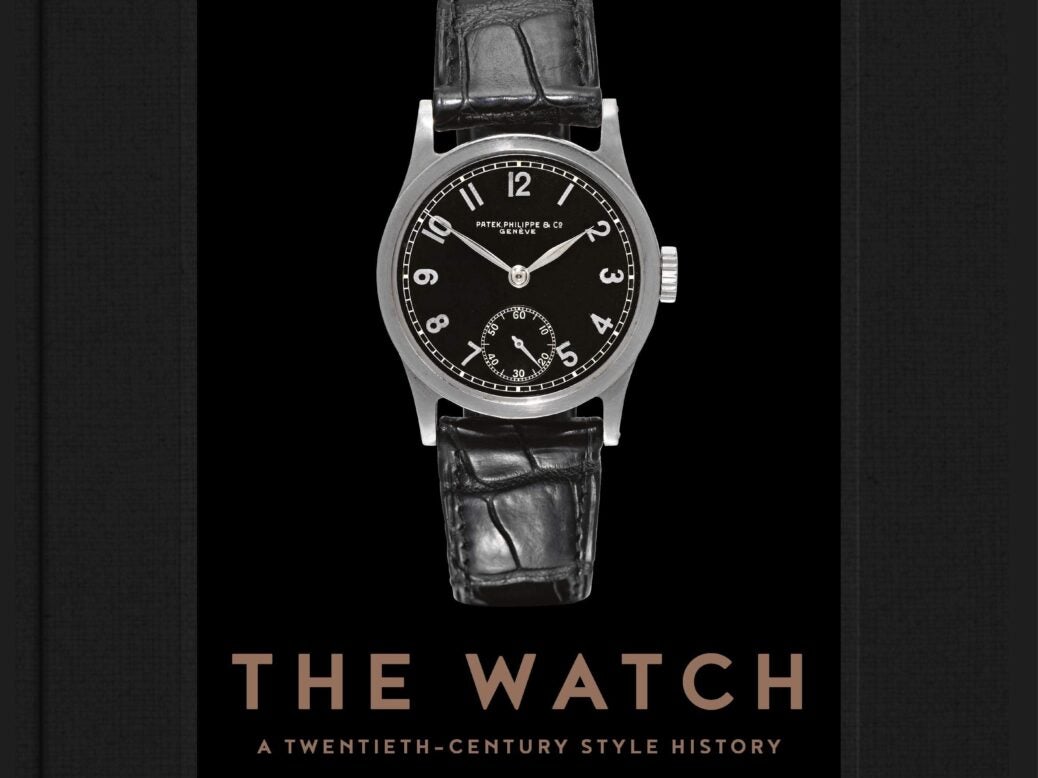

Patek Philippe retailed by Gondolo & Labouriau in 1924. An 18ct yellow gold oversized, curved rectangular wristwatch. Image © Sotheby’s

Prior to this, the thought of placing a delicate mechanical object on the wrist was anathema to many who viewed the wristlet as little more than a gimmick. Dirt, moisture and knocks are all enemies of the mechanical movement, so moving the watch out of the safety of the pocket left it dangerously exposed.

For the watch manufacturers, however, the wristwatch offered potential marketing benefits. It could be adapted for specific uses or occasions, thereby encouraging multi-watch ownership. Different models were, for example, designed for use by doctors, drivers of motor cars, swimmers and other sports enthusiasts. Sleek and slim dress watches or opulent gem-set models were created for special occasions or evening wear.

Watches of Wall Street

Innovation and experimentation in wristwatch design gathered pace during the 1920s, but seemed in danger of screeching to a halt with the impact of the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression that followed. Yet despite this seemingly cataclysmic turn of events, the 1930s proved to be one of the most innovative and creative decades for watch manufacturers in the whole of the 20th century, and the influence of that decade can still be found in watchmaking today.

During the Second World War production shifted towards the supply of the armed forces on both sides of the conflict and there were severe restrictions placed on the import of civilian watches into many countries. The post-war years would see design elements that had been developed for military watches adapted for use in new models created for the civilian market. A prime example was Omega’s so-called W.W.W. model, a robust waterproof wristwatch that inspired the brand’s civilian Seamaster line.

Rolex Cosmograph Daytona ‘Paul Newman’ Ref. 6239, c. 1968. A steel chronograph wristwatch with registers. Image © Sotheby’s

The rise of Rolex

The 1950s witnessed a golden era of mechanical watch production; it was the era in which Rolex would launch some of its most iconic models, such as the Explorer, Submariner, Milgauss and GMT. However, the 1950s also saw the first clear signs of a future beyond the mechanical movement. In 1957, Hamilton released the first series produced electric wristwatch – whilst this was a mechanical movement incorporating a traditional gear train and balance, crucially, it had been modified for electrical impulse and was powered by a battery.

Although this early form of electrified movement was beset with performance issues, the race was on to produce a mass market, fully electronic movement that would dispense with the watchmaker’s art entirely. Ultimately this would lead to what is known as the ‘quartz crisis’, a period that would see the near decimation of the Swiss watch industry in the second half of the 1970s and the early 1980s as cheap quartz watches from America and Japan began to flood the market.

Girard-Perregaux Three Bridge Tourbillon, introduced in 1991. An 18ct pink gold skeletonised tourbillon wristwatch. Image © Sotheby’s

A mechanical renaissance

However, even in the midst of the darkest days of the quartz crisis, at the start of the 1980s, the seeds of the mechanical watch’s renaissance were being sown. Whilst many watch brands were swept away and others mothballed or amalgamated, there were still enterprising watchmakers, investors and entrepreneurs, such as Nicholas Hayek (later CEO of the Swatch Group) and Jean-Claude Biver (now chairman of Hublot and Zenith), who believed in the mechanical watch’s potential. Their determination would ultimately lead to a spectacular turnaround in the fortunes of some of the oldest watchmaking firms including Blancpain and Breguet. As the 1990s opened, a fresh confidence was breathing new life into the traditional world of the watchmaker.

By the end of the twentieth century, the design of the watch appeared to have come full circle. Stylistic elements from the 1920s to the 1970s formed the basis for many models and reinterpreted or reissued vintage designs (such as Franck Muller’s Curvex Cintrée) played an important part in the offerings of the major watch brands. However, the quartz crisis and its aftermath forced the industry to innovate in order to survive. A new wave of talents such as Philippe Dufour and Roger Smith had introduced a fresh dynamic that frequently challenged established traditions. At the dawn of the new millennium, demand for luxury watches continued to gain momentum and a new air of confidence pervaded – the mechanical watch’s renaissance seemed all but complete.

The Watch – A Twentieth-Century Style History by Alexander Barter is published on 16 September 2019 by Prestel