Lorenzo Lotto has posthumously routed his better known contemporaries Mantegna and Bellini, writes Christopher Jackson

We’re particularly impressed by the country boy who makes it big in the town. History furnishes its examples: there’s that Stratford-upon-Avon bumpkin who dominated the London theatre scene for a bit in the 1590s and the 1600s; or that fellow from Vinci – a bastard of all things – who made a splash in Florence and Milan. ‘If I can make it there, I can make it anywhere,’ as Frank Sinatra sang.

Lorenzo Lotto (1480-1556)’s career works rather in the opposite direction. He was born in Venice into a city where Mantegna (1431-1506) and Giovanni Bellini (1430-1516) were supreme. That pair – related as a result of Mantegna’s marriage to Bellini’s sister Nicolosia – will be slugging it out to a score draw in the Sainsbury’s wing of the National for another few weeks. They overshadowed Lotto in their lives, but in the more important posthumous contest, there are signs that Lotto was all along the better truth-teller of the three.

Lotto seems to have had a certain restlessness: he left Venice in 1503, and ended up reporting on provincial society. He went to Treviso (1503-6), the Marches (1506-8), and Rome (1508-10) before settling for an extended time in Bergamo, north-east of Milan. This decision engendered an extraordinarily fruitful period from 1513-25.

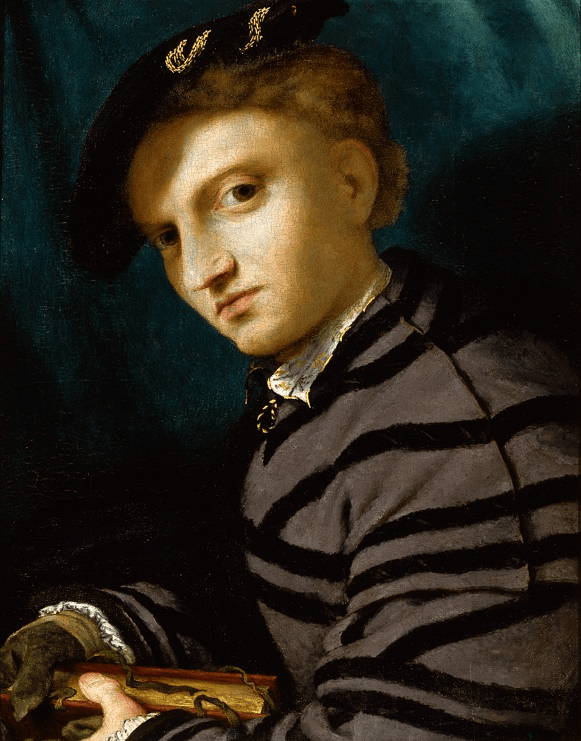

This exhibition begins with a room which makes you realise how right he was to leave a Venice in the first place. It seems to have hampered his invention. Here we find a remarkably unpromising artist, dedicated to weird elongations and distortions, and null essays in the Bellini style. One such is the Portrait of a Young Man (1500), where the sitter’s oddly oval features seem inherently unlikely: it’s suggestive of someone attempting a new method of seeing, when he hasn’t yet learned to look for himself.

What happened to Lotto in Bergamo? The second room suggests a simple answer: he made many friends. To enter this exhibition space is to feel oneself present at a sort of cocktail party full of the Bergamot well-to-do. In addition to Lotto’s friendly landlord, there are doctors and merchants, people about to be married, and those about to start families. It’s a party where all the participants share a sense of humour.

Friendship in this smaller society liberated Lotto: for the rest of his career, his pictures would contain in-jokes, and objects painted as references to his subjects’ lives. They are playful celebrations of the quiddity of each life. Granted access to this circle – in a way which would have been difficult for him amid the austere politics of Venice – he was able to say with a clarity which has remained undimmed across five centuries, what was going on in these people’s lives.

Take for instance Messer Marsilio Cassotti and his Wife Faustina – painted in 1532 (see below). Marsilio is marrying up, and there’s a cat-that-got-the-cream knowingness about his look. Cupid also seems in on the joke, glancing sideways at him in congratulation. Or perhaps he’s simply asking to be thanked: love can be a great boon to bank balances. But Faustina is smiling too – we are in a wholly convivial setting, where there is no tension enacted between sitters. This might make for a facile picture, except that Lotto paints so precisely as to remind us that the tension is located elsewhere: in the fact of time acting on youth, and on all ours moments of happiness.

The picture also reminds us that Lotto is the great painter of fabric. Look at Marsilio’s marvellously billowing attire, and the spacious way in which light is caught on Faustina’s pink gown, as if a little star were lodged there. There is an impressionistic freedom here, a delight in the material world, which would only be approached in subsequent centuries by Vermeer and Ingres – and then only occasionally.

It’s a talent shown again in another picture, also called Portrait of a Married Couple (beneath). Here, the tablecloth is rendered so lovingly as to be transfigured by the artist’s attention into something hyperreal, even numinous. And again, the cosy interior scene –with its traditional reference to fidelity in the shape of the dog – is also being acted upon from without: this time by the tempestuous weather outside.

Lotto was, at this stage in life, a happy man. One realises this especially in the last two rooms, when the mood sours. The exhibition can feel like a kind of dramatised reminder: beware the idea that you’re indestructibly on a roll. More specifically, if you are ever 95 per cent happy but five per cent restless, don’t let the smaller number dictate the larger. Productive contentment is rare, and will likely not be replicated elsewhere.

I say this because the cause of Lotto’s sad last years appears to have been his decision to leave all this, and return to Venice, which he did in 1525. In his home town, he still painted marvellous pictures: but the intimacy between artist and subject had gone, and along with it, the Lotto playfulness. This was now a Venice dominated by the capacious genius of Titian (1488/90-1576) – a greater artist than either of Lotto’s original competitors, Mantegna or Bellini.

It seems as though Lotto did make a mark on the great man’s imagination. It is hard not to feel that Lotto’s highly original, even proto-Cubist work Triple Portrait of a Goldsmith (1525-35), wasn’t somewhere in Titian’s mind when he painted The Allegory of Prudence some 15-25 years later. If so, then it’s a sign of Eliot’s adage: ‘good writers borrow, great writers steal’. It is a brief window into the omnivorousness of Titian’s genius.

Titian, Allegory of Prudence, 1565-70, National Gallery

It wasn’t a drastic decline; in fact Lotto painted some of his best portraits when back in his home town. Flashes of the Bergamot humour remain, but these feel almost like moments of nostalgia for the place where he had really been welcomed. There is, for instance, the bright flicker of the lizard in the otherwise sombre Portrait of a Man with a Lizard (1530-2), or the Cupid pissing into a pot at the back of the portrait of Andrea Ordoni (1527).

But the medium has changed. It’s humour carried on in a vacuum, and no longer conducted within a community which the artist really remains a part of once his brush is down, and the canvas rolled away. One sees this replicated elsewhere in the heaviness of the Portrait of the Architect (1536): these are not Lotto’s friends.

Lotto fell on hard times from there: we can infer that he had fallen from favour, and his pictures – autobiographical to the last – tell of this misery. The humour has gone; there are few sadder things than a man who used to laugh, who no longer can. But it’s not uncommon: the inventor of the young Natasha Rostova ended up writing The Kreutzer Sonata.

Despite this gloomy trajectory, the viewer’s mood on exiting this superb exhibition is not so much misery at his ending up, as elation at what he did achieve. Lotto is a reminder that you don’t have to have been deemed in the front rank in your lifetime to have been granted the full human truth and thus partake in the contest of posterity.

Christopher Jackson is deputy editor of Spear’s

Lorenzo Lotto Portraits is at the National Gallery until 10th February

Main image credit: Lorenzo Lotto, Portrait of a Young Man with a Book, about 1524–6, Oil on panel, 34.5 × 27.5 cm, Pinacoteca del Castello Sforzesco, Milano © Comune di Milano, tutti i diritti riservati / Photo: Saporetti 2001