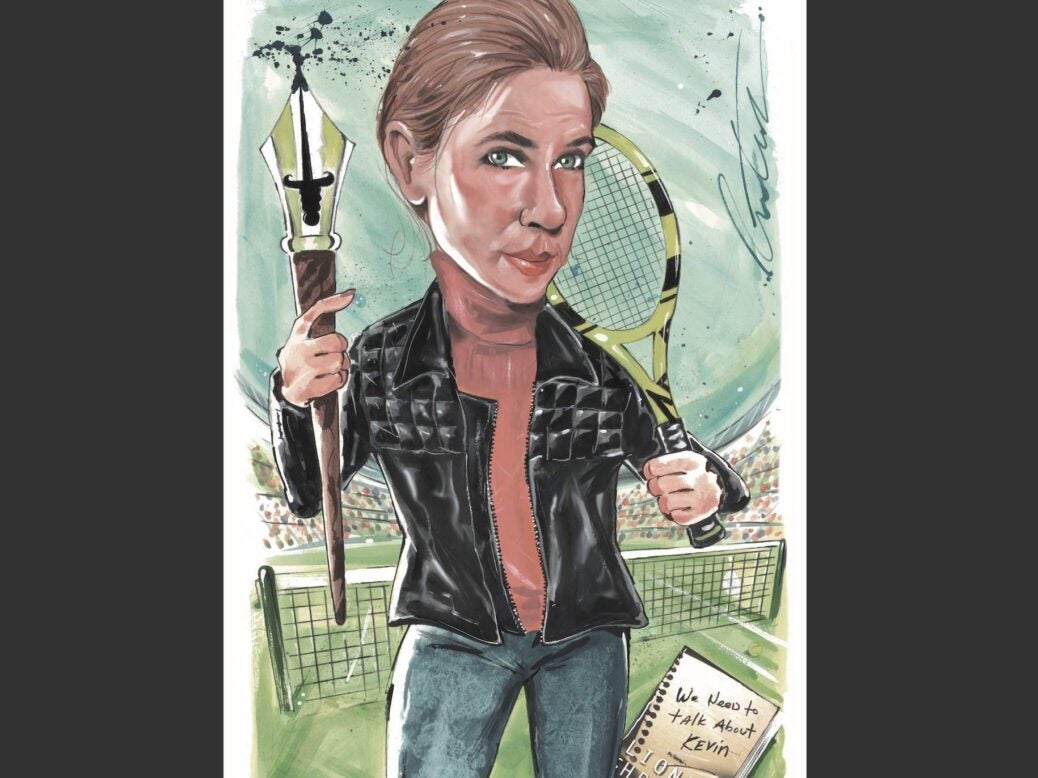

The author and journalist shares her views on hoarding, lockdown, obsessive exercise and ‘cancel culture’

How much is an ounce of gold?

I’m guessing about $1,800.

How did you earn your first pay cheque?

I worked at the Ice Capades Chalet in Atlanta, Georgia. I was the receptionist and it was very poorly paid. It’s influenced my politics from there on. As one does, what I thought I was getting paid was not what I was getting paid. In other words: taxes.

Would you consider yourself more of a saver or a spender?

That’s an easy answer. I’m definitely a saver. In fact, I’m a hoarder, not of objects but certainly of money.

What has been your favourite thing about lockdown?

Having more time to get my work out.

And your least favourite?

Not being able to see my friends. I think that’s a pretty severe deprivation. It takes a long time to cultivate a group of people whose company you can bear. You shouldn’t go too long without seeing each other. Now we’re just going months on end without seeing anybody. It’s very fortunate that I’m happily married or I’d sure know it by now.

Live to work to work to live?

I’m much more in the live to work category, because I enjoy my work, especially the fiction side versus the journalism side. I enjoy writing fiction, and it is a pleasure. So there’s no distinction for me between work and play. And that makes me extremely fortunate.

Where are you happiest?

On the tennis court. Singles or doubles? Singles. I’m not a joiner of any sort. I don’t like group activities.

What is your greatest fear?

Returning to a place I briefly occupied where I couldn’t publish any more. I couldn’t get my books into print and that prospect is forbidding. And I guess right next door to that is running out of ideas, so there aren’t any books to get into print. That’s probably even worse. You’ve written a lot about freedom of speech.

Do Spear’s readers need to worry about ‘cancel culture’?

That’s connected to my greatest fear. Cancelling, in my case, would involve making it impossible to publish my work. So I am actively wary of that happening to me. However, I do not allow it to muzzle my opinions or my willingness to put those opinions out in both fiction and non-fiction. I’m hoping that I don’t end up being sorry about that. Your new novel talks about the ‘cult of fitness’.

What is it and how do we avoid it?

It’s a book about exercise and it’s not exactly anti-exercise; that’d be like being opposed to koala bears or something. But it is a book that’s unenthusiastic or at least ambivalent about the way in which we have elevated exertion to the highest possible good.

The people who get involved in these endurance sport events tend to regard what they’re doing as a higher calling, as if they’re actually accomplishing something, and they’re not. It’s a vanity project. The book is about a couple, and when the man gets involved in endurance sport he becomes an intolerable narcissist.

I’ve had confirmation from a reader who said that she has met several women who are married to men who got involved in triathlons, and they’re all divorced.

What would you like your legacy to be?

A stack of readable and entertaining books. I think that’s plenty.

The Motion of the Body through Space is published by the Borough Press