PORT AND FIVE-STAR BOARD

In the Unesco-listed historic centre of Oporto on the bank of the Douro, crumbling houses tiled with azulejos rise above the riverside merchants’ walls and teeter above narrow cobbled streets that lead into squares pregnant with the exuberant edifices of Catholicism.

Yet in both the history and architecture of Portugal’s second city, the influence of Albion is writ large. Amid examples of Manueline architecture, imposing neoclassical buildings of granite smack of more northerly climes. And nowhere is British presence more pronounced than in an eccentric institution that survives to this day, an anachronism said to be the last remaining example of its kind in the world.

It is an elegant, loggia-fronted building of yellow granite, grand as any to be found in London’s traditional clubland, that stands on the Rua Infante D Henrique — formerly the Rua Nova dos Ingleses. Designed with four storeys in Palladian style by the British consul, John Whitehead, it was completed in 1790. This ‘Factory House’ was originally built for British merchants (‘factors’) of Oporto trading in wool, cod and wine, who had thrived since the beneficial terms of a treaty of 1654.

The port shippers, as the most prosperous of these merchants who had funded the construction of the building, were granted exclusive rights in 1811 and it remains their private club today. Full membership of the Factory House is still restricted to British directors of British port companies. There are but twelve full members in this gloriously colonial outpost of Pall Mall: up from eleven three years ago, when a lady was voted in for the first time in the Factory’s history.

‘Voting is secret, using black and white beans,’ says Paul Symington, head of the dominant Symington clan, who currently account for at least five of the members. ‘Two black beans and you’re out.’ The eligible pool, it should be noted, is not large, with just three British port families still in business: the Symingtons (Graham’s, Dow’s, Cockburn’s and Warre’s), Bridge-Robertsons (Taylor’s, Croft, Fonseca), and John Graham (Churchill).

Pictured top and above: The Factory House in Oporto

In the vaulted entrance hall, where sedan-bearers once awaited their masters, wooden panels are inscribed with the names of the Institution’s annual treasurers since 1811, the names dwindling over the decades to a recurring handful.

Occasionally, as in 2010, the role of treasurer coincides with that of honorary British consul (who is there to help Brits abroad in trouble). ‘The tradition goes back hundreds of years, when the factors elected the consul,’ says Symington, leading me up the grand, cantilevered granite staircase with its locally made wrought-iron balustrade.

On the walls, lit by a domed skylight, hang portraits of consul John Whitehead and his grand-nephew, Lieutenant-General Sir William Warre — who once joined the eponymous family firm only to be sacked for gluing the pigtail of a partner to his desk as he slept.

‘The consul used to reside here, as did the vicar, who held services in the ballroom, until permission was finally given to build the Anglican Church of St James in 1815,’ says Symington. ‘It was designed with the same dimensions as the ballroom and concealed behind high walls, so as not to corrupt the locals.’

Royal assent

From its earliest days, the Factory served as a glittering social hub which, as one Mr Kingston, banker to Lord Carnarvon, wrote in 1845, ‘the higher classes frequent.’ Lit by crystal chandeliers, the Wedgwood-blue ballroom, complete with sprung floor, minstrels’ gallery and dance cards — when not doubling as chapel — witnessed extravagant functions in honour of European royalty.

Among visiting British royals was Queen Elizabeth II, who in 1957 expressed her surprise at finding her Order of the Garter on a ballroom curtain (still there). Her signed photograph, along with those of other members of her family, Churchill, and portraits of notable port shippers, is to be found in the drawing room, where Nick Heath, the current treasurer, awaited us, proffering sherry.

Pictured above: Fine dining at the club

It was a Wednesday, the day lunch is held for members and their guests — provided at least eight persons are present. In this unchanging corner of England, an immaculate copy of The Times from exactly 100 years ago is laid out every Wednesday for members to peruse.

‘The earliest issue dates from 1812, with every copy preserved since 1816,’ says Olga Lacerda, who has for years taken charge of the daily running of the Factory. The Times, incidentally, was just one of 43 British periodicals to which the institution subscribed, according to a receipt of 1870 from newsagents Cowie & Co of London.

Few chattels predate the occupation of the building by the French, between 1807 and 1809, during the Peninsular War, and the return of the Factory to its owners in 1811. Photographs record the celebratory feast held, with rented furniture, at 11am on 11 November of that year, along with the menu of eleven courses and eleven wines, signed by all eleven full members. This feat of endurance was repeated and recorded exactly 200 years later, ‘after which’, adds Johnny Symington, cousin of Paul, ‘I walked the exactly 11km home.’

Among the earliest surviving artefacts is the framed copy of the 1809 proclamation by Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington — leader of the British forces — enjoining the inhabitants of Oporto to ‘treat with compassion and humanity those [French] soldiers who are still in the city either due to illness or imprisonment’. It hangs in the map room, whose charts record an age of exploration still in its adolescence.

Pictured above: Sir William Warre was sacked from the family’s port firm for a practical joke

Above the fireplace, pride of place goes to JJ Forrester’s 1848 watercolour map of the Douro and its vineyards, to which the port shippers owed their wealth. Tracing the river’s course from the Spanish border to the Atlantic, it earned Forrester, himself a member of the port confraternity, the title of Barão de Forrester and immunity from customs duties.

Among the huge maps of the world that hang from rollers, that of Africa, published in 1835 — anteceding by some 23 years the discovery of the source of the Nile — exposes a vast, blank, uncharted interior. ‘Moombos,’ reads one area, roughly corresponding with today’s Zimbabwe. ‘Said to be shepherds, but cannibals.’

Time lapse

Adjoining the map room, the three womb-red rooms of the library, once the domain of the consul and vicar, hold further curiosities. The extensive collection ranges from How to Be Happy though Married to a rare copy of David Ricardo’s 1817 Principles of Political Economy and Taxation.

A first edition of Keats’ Endymion, purchased for 12s in 1818, has been removed to the safety of a cabinet in the reading room, along with Darwin’s Voyage of the Beagle (1839) and On the Origin of Species (1859) and two volumes of Johnson’s dictionary. It is a place to while away many happy hours, perusing the visitors’ book (‘Captain Haddock, 12th Caçadores, May 14, 1812’) and the trivia of letters of the period, overwritten in both horizontal and vertical script, to save paper. Lunch, however, was announced.

A rare concession to the 21st century lies in the kitchens. The original kitchen, located on the top floor (a common practice due to fire risk), has been preserved with its 19th-century English ranges, pots and pans, and leather fire buckets (dated 1790). Water was drawn from a well beneath the building, via an extant pulley system, and for many years the Factory employed its own ‘Master Fireman’.

Happily, there was no call for this office as we trooped into the dining room. Two dining rooms, in fact, the one segueing into the other, with identical tables each comfortably seating 36. And herein lies one of the unique rituals of the English Factory. After dinner, each guest rises and repairs to the dessert room, to an identical placement at an identical table, to enjoy dessert and vintage port, untainted by any noisome whiff of food.

‘Our dinner was superb,’ wrote a guest at a dinner for General Sir Thomas Stubbs in 1827, ‘and we adjourned from the table to another room, en suite with the first, where such a dessert and such wines were served up, as quite to astonish our northern experience.’

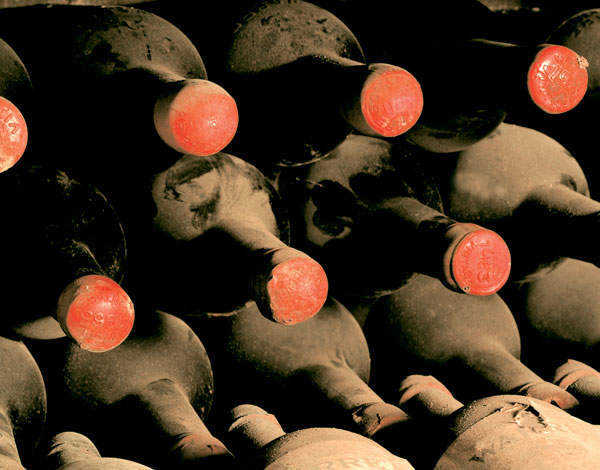

Lunch, if less formal, was equally decorous, an emanation of the host country materialising through the Factory’s 1.2m thick walls in the form of salt cod and black pig. The wines, predictably, were excellent, the meal ending with the traditional blind tasting of a vintage port, chosen by the treasurer from among the 14,500 bottles donated by the member houses in the Factory cellars. Rumour has it there are still some bottles which predate the outbreak of phylloxera in 1868.

It was time to retire. To the billiard room? There is one, only the baize is now moth-eaten and the pockets worn through. One can imagine the post-prandial fun of ages past. A last bastion of tradition, as WH Harrison, a visitor who enjoyed the hospitality of the English Factory, wrote, in 1839: ‘Of all the towns in Portugal, Oporto is that in which the Englishman will find himself most at home.’

THINGS TO DO IN OPORTO

- The Yeatman, a wine-themed hotel – has opened above the steep banks of the Douro, on which the last rabelo laden with pipes of port sailed from the Douro Valley in 1964.

- Attached to Graham’s still-functioning 1890 cellars is a museum detailing the company’s history, along with slick new tasting rooms and a deliciously contemporary restaurant, Vinum.

- From fine dining to fine art, the Serralves Contemporary art museum, with its magnificent 44-acre park, is worth a visit.