BAY OF PLENTY

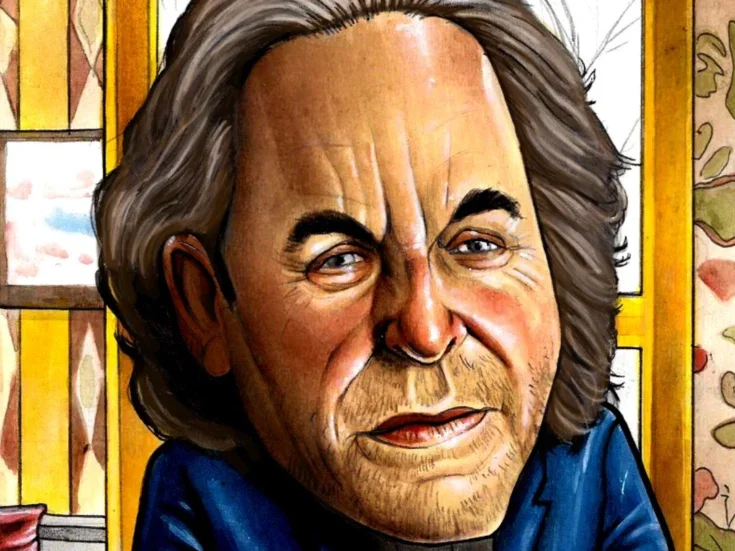

Mariano Rubinacci is best known as a tailor of ethereal genius. His father started a tailoring house in Naples between the two world wars and effectively identified what has since become known as the Rubinacci look.

While it is often ‘interpreted’ by others, they never quite manage to capture the soul of his work, a soul derived from his deep sense of culture and sensitivity to the arts — in short, his connection to the essence of what it is to be Neapolitan.

Until the Risorgimento this lively coastal city was the capital of the Kingdom of Naples and the Two Sicilies, with a palace on every street corner and sufficient princes, dukes and barons to fill several volumes of Debrett’s. And, like so many capital cities, Naples is a place of multiple personalities.

About ten years ago, I wrote a book about the bisexual gambling dandy and political fixer Count d’Orsay. His intriguing personal life found him located for some time in a Naples which sounds like the St Tropez of early-19th-century Europe — a pleasure-loving, permissive society that attracted aesthetes and artists.

Read more on travel from Spear’s

How different, then, to the city of crime and grime that Spear’s editor Josh Spero encountered when he visited the city of dolce far niente and wrote about his experiences in these pages some seven years ago.

Clearly the scars of that visit (of which he said that Vesuvius had buried the wrong town) are barely healed; nevertheless, he wanted to give Naples a fair chance to redeem itself. And to be fair, the first time I visited Naples my expectations were similar — if I escaped uninjured with my life intact I felt I would be doing all right, and to leave carrying all my possessions would be the definition of quitting while ahead. However, instead of tolerating Naples I learned to love it.

First, and most importantly, this is because a Neapolitan was my cicerone. Mariano is as much at home in New York as in Naples, so he has the eye of a cosmopolitan and the knowledge of an insider. Thus he knows, for instance, that I would appreciate the guy who makes the best lemon juice in the city from Sorrento lemons the size of children’s heads.

Indeed, food is one of the principal pleasures of this part of the world. During the summer the delights of the Amalfi coast come to life and La Conca del Sogno in Nerano, best approached by boat, is a magical place to enjoy a long summer lunch.

Personal palace

While the popular picture of Naples is as a city of crime, I see it primarily as a city of culture. Seeing the palaces of Capodimonte and Caserta was a revelation. I was told that the collection of paintings and what have you in Capodimonte is second only to the Uffizi’s, but I have no way of verifying this because in Florence I have been put off by the tourists. By contrast, when I was in Naples I had entire galleries to myself, as well as the National Museum of Archaeology.

Wandering around these remarkable works of antiquity, I found myself remembering Shelley’s Ozymandias, with the exception that the works on display here were in far better shape than the trunkless legs about which Shelley wrote.

Back in the day (the day being the 16th century), if you were a big shot you could just dig this stuff up and plonk it in your garden, or if you were really grand like Alessandro Farnese (aka Pope Paul III) you could have Michelangelo knock up a couple of niches in which to show off your latest acquisitions.

Of course, from the 18th century onwards, following the excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum, the Naples region was the centre of the world if you were a Grand Tourist souvenir hunter. Simultaneously the place was also le dernier cri in Contemporary art, as was made clear to me when I visited the Chapel of Sansevero.

This masterpiece of the late baroque is what the French would call éblouissant, enough to bring on a bout of Stendhal syndrome, and yet it is located down the sort of malodorous alleyway that would hasten an attack of Spero syndrome in the most intrepid of travellers.

It includes both the macabre and the magical. The macabre is supplied by two flayed corpses in the basement which exhibit just the bones and the circulatory system preserved by 18th-century wizardry. The magic comes courtesy of the sculpture of the veiled Christ: the shroud may be marble but veins, knuckle and the rest remain visible. It is a tour de force and, although made of marble, seemed possessed of the ineffable lightness of one of Rubinacci’s whisper-weight suits.