TOP OF THE TREE

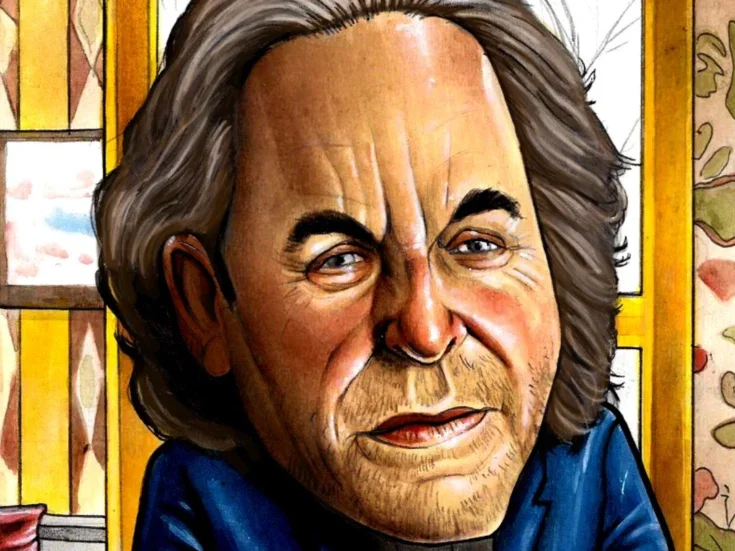

There’s not much a Singaporean prison and a global luxury resort chain can be said to have in common. They have, however, at different times shared the pleasure of KP Ho’s company. Born in Singapore into a successful industrialist family and educated in America, Ho (pictured below) was a little too free-speaking as a journalist for the taste of the government; his reward was two months in jail. It’s a long way, then, from captivity in a harsh prison cell to the freedom of a stay in one of his light-filled, romantic Banyan Tree villas — or perhaps not really far at all.

Trained as an economist, Ho went about starting Banyan Tree in the most idealistic, least practical way possible, he tells me over coffee in a small, rococo London hotel. ‘I never even knew the phrase “due diligence”, so I bought a small piece of land in Phuket for a summer house and then walked around the beach and saw this big piece of land, totally denuded, without any trees, no sign of animals or birds, with this very eerie aura. On a whim we bought it because it was so cheap, and we subsequently discovered that it was so cheap because it was totally polluted.’

A not so smart start, then. But with the necessity that comes from invention and the entrepreneurial (or journalistic) skill of making a negative into a positive, Ho and his wife turned pollution into conservation and the lack of a beach into the private pool villa concept. Twenty-six resorts later, Ho has established a clear and winning identity for Banyan Tree: luxury without opulence, service without suffocation, romance above all.

Ho sees himself as a bridging figure, someone who can take his Western education and his Eastern roots and meld them into a more harmonious form of business and leisure. He is free with his criticism of both sides. Take China’s approach to the service industries: ‘In China every hotel charges a service charge but they never pay it out to the staff — none of the big chains — because the owners all want to keep it to themselves. We’re the only chain in China where we refuse to manage a hotel unless a service charge is paid out 100 per cent to staff.’ This makes for happier staff, ideally.

But the West can be overbearing too, for example with its environmentalist obsessions. Ho once said that ‘protection or promotion of the environment cannot be at the expense of people’, and he reiterates that in our conversation: ‘I think there’s not a sufficient awareness among the Greenpeaces of the world that sometimes there are economic trade-offs and you cannot always just have a win-win situation. When you want to stop dams, fine and good, but there are also economic consequences; unless you find alternative ways of promoting development, it may be condemning people to a less certain economic future.’

If he had to balance saving an endangered snail species with providing dozens of jobs to the area around a Banyan Tree resort, it’s clear which way he would tip.

For the love of money

But what he really rails against are the developers who only see money. Creating a resort is an opportunity to nourish — or ravage, environmentally, socially and culturally. His annoyance pours out: ‘People design a hotel, they raze the land, all the soil goes into the ocean, kills the corals, they build this horrendous piece of architecture — that’s on the physical side. And then they bring in all these fat Russians and Germans and others coming down who pay in one day what is equal to the entire monthly salary of a worker, and you get social contradictions developing, you get resentment. Even though they are employees at the hotel, they resent the people who give them their livelihood — we see this all the time.’

There is something admirable in a man not afraid to alienate some of his potential customers. It is not, of course, their nationality which makes them unpalatable, but their outlook. ‘Bling’ is not a word he enjoys. The ideal Banyan Tree guest, he suggests, is someone who has survived the trial of being nouveau riche and reached a level of refinement where they travel for new cultures and the romance of the journey.

Tourism is certainly one of the best industries to be in at the moment in China, given the government’s push for greater consumption by its citizens, with its active promotion of travel within China’s borders ‘rather than just paying lip service to it’. Banyan Tree now has ten resorts in China — not just Macau and Shanghai, but also the mountainous terrain of Yangshuo (opening this year) and Lijiang, ‘the Venice of the Orient’.

With the hundreds of miles of high-speed railways recently built and the dozens of new airports under construction, it is getting ever easier for the Chinese to exploit their wealth. One report says that Chinese consumer spending will grow by over US$2 trillion by 2020, which is a lot of internal flights. Another predicts that there will be 280 million middle-class households in China by 2025 — a burgeoning travel market. Moreover, there is a strong streak of national pride one can trade off in China, says Ho: ‘With a 5,000-year-old continuous civilisation, every schoolkid in China knows virtually every one of the places that anybody would build anything.’

Moving on

China’s 5,000-year-old story is reaching an interesting twist, along with much of the rest of Asia, a twist which Ho has smartly observed and taken advantage of. In short, he has seen that the era of the large Asian industrial group making things for foreign companies is fading: ‘Our family businesses were a microcosm of the typical Asian mini-conglomerate, jack of all trades, master of none. We did contract manufacturing, we did trading, we did agency representation of trading, the clever stuff that Jardines would do but on a bigger level.’ But what was the point? Your margins were squeezed so ‘you just run to stand still’.

Those who benefited were the big Western brands getting labour on the cheap. And when you got too big, the principal bought you out and you had to start again.

While this model creaks but continues, rising beside it is a more sustainable capitalism, or at least a self-sustaining one — one where Asian brands work for themselves. Banyan Tree’s business model ‘is not so much about how we treat our associates and all that, but what is immutable and what people do follow is that we’re one of the very first companies in Asia that said we would develop our own brand from scratch…

Only if you have a brand proprietary to yourself might you be sustainable in the future because you have to ultimately own your customer.’ This, he says, is ‘the new face of Asian capitalism’, coming about in tandem with the growing wealth of Asian consumers.

Not that this new capitalism can automatically thrive: Ho wants Banyan Tree to get to the point, possibly with 50 hotels, possibly with a hundred, possibly more, where he can ‘reach the far bank’ of the river without being ‘eaten up by the crocodiles’ taking the weaker. He cites some similarly luxurious mid-size hotel chains which have been eaten, either disappearing entirely or being bought by a larger group. He won’t actually say how many more hotels he wants (‘hubris’), but he wants to be independent, and he needs enough hotels and sufficient customer loyalty to intertwine to make that happen.

Crossing continents, with two well-regarded Mexican resorts in the Americas, is helping, but I feel the Banyan Tree concept will be a harder sell outside of the spacious tropics — it is tougher to distinguish yourself in a crowded urban market. Then again, the urbane Mr Ho ought to have no trouble doing that.