A haunting bronze bust, elongated, flattened and grooved, Alberto Giacometti’s Grande tête mince (1954) seems shaped as much by memory and erosion as by flesh. Stark and hollow-eyed, it distils the human face into a mask-like form. Often associated with Giacometti’s brother Diego, the work transcends portraiture. It becomes a symbol of introspection, its pitted texture quietly speaking to time, vulnerability and endurance.

When it went up for auction in New York in May, Grande tête mince had an estimate of $70 million. But then something astonishing happened. This quality work from one of the most vaunted artists in human history failed to attract a single bid. If you were there, in Sotheby’s saleroom on York Avenue, you might have almost felt the shockwaves rippling across the art world. When a major work fails, it plunges demand for other pieces – not only those by the same artist, but also trophy pieces from other names in the canon – the Warhols, Picassos and Rothkos too. If this didn’t sell at that price, what will? The unsold bust became an avatar of what some see as a crater in the market for ultra-high-value art.

The failure came against a gloomy backdrop. According to the 2025 Art Basel/UBS Art Market Report – held in oracular esteem – global sales fell by 12 per cent in 2024 to $57.5 billion.

That’s the second largest drop in 15 years, leaving total sales down more than $10 billion on 2022.

[See also: How to avoid buying stolen art – and what happens if you accidentally do]

Art sales take a hammering

According to Arun Kakar of online sales platform Artsy, any downturn is in danger of becoming a spiral. Today’s cool market conditions are ‘leading to a lack of consignments [collectors putting their works up for sale], creating a nasty cycle. People are less likely to consign because they view a lack of demand, which in itself affects demand. There’s also the contextual issues of tariffs, stock market trickiness and so on. Auctions are driven by sentiment and emotion, so the houses are more susceptible to changes in mood music than large businesses in other industries.’

Look beyond the big-ticket items, however, and perhaps it’s not so bleak. The actual number of transactions rose by 3 per cent to 40.5 million last year, suggesting resilience in lower and mid-tier segments. Private sales were estimated to have risen by 14 per cent. The US retained the top spot for market share (43 per cent), while China’s sales fell 31 per cent to $8.4 billion, pushing it behind the UK. The market, in short, is not collapsing but rebalancing. A number of the art world experts who spoke to Spear’s for this article suggest a cooler, leaner, more selective phase has begun.

The major auction houses, however, have felt the chill. Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Phillips saw sales fall 19 per cent in 2023 and another 26 per cent in 2024. Christie’s dropped from $8.4 billion in 2022 to $5.7 billion. Sotheby’s revenue slid 23 per cent to $6 billion, softened only by a $1 billion bailout from Abu Dhabi’s ADQ. Moody’s and S&P still rate its bonds as highly speculative. Phillips saw a 14 per cent drop. Bonhams declined 12 per cent but dismissed it as cyclical.

Further darkening the outlook is data from Mei Moses, a Sotheby’s-owned specialist in repeat auction sales. It reports that average returns on artworks have dropped to their lowest since 2000 – virtually zero. Some of the biggest names have taken hits. Rothko’s Untitled (Yellow and Blue) sold for $46.5 million in 2015 but fetched only $32.5 million in 2024 – a 30 per cent drop. Koons’ Balloon Monkey series plummeted 60 per cent over a decade. María Berrío’s La Cena, bought for $1.5 million in 2022, resold for $441,000 in 2024 – a 71 per cent dive. For collectors who saw art as a hedge or haven, this is sobering news; many are choosing to hold, to avoid crystallising their losses.

New money, new tastes

Not only are many of the auction houses’ clients keeping their hands firmly in their pockets for now, some may soon disappear – or at least be replaced. The ‘Great Wealth Transfer’ is expected to see baby boomers pass on an estimated $84 trillion in cash and assets to younger generations over the next two decades. This is likely to catalyse a surge of inherited collections coming to market, but it could also precipitate a profound shift in the profile of buyers and collectors, which would be accompanied by a transformation of the prevailing tastes and dynamics.

Such a step-change is likely to redirect funds toward emerging artists and digital media, empowering younger, socially conscious collectors. According to Katie Carder at Phillips, the transformation would encompass ‘digital technology, innovation, evolving definitions of collecting, and how the art market is connecting with the next generation – all factors that seem to be influencing these structural shifts’.

Gen X is the most art-hungry demographic. Having surveyed 3,600-plus HNWs, Art Basel/UBS came up with a mean self-reported art expenditure figure of around $578,000 per year, per collector, on art as of 2023. Emerging artists and digital work are taking an increasingly large share, with 52 per cent of recent art spending going towards new or emerging artists – up 8 per cent on previous years, reflecting a growing appetite for innovation and fresh perspectives. This is already extending into new ownership models, fractional investing and digital platforms – a broader transformation in how art is valued, collected and consumed.

To respond to these structural changes, salerooms are pivoting away from the stately-home clear-out and trying to engage with the tastes and demographics of a new generation of collector: younger, more digital in outlook, and more likely to hail from Asia or Africa. All the big four have recently made major moves to help them navigate the changing landscape.

Brennan has a tough act to follow. Under her predecessor, Frenchman Guillaume Cerutti (who has stayed on as chairman), Christie’s sold 10 artworks for more than $100 million each, including Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi for $450 million in 2017, as well as the collection of Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, which raised $1.5 billion, the largest ever sale of a collection at auction.

In January, Christie’s appointed Bonnie Brennan as chief executive. A wholesome, blonde, Michigan-born Irish-American saleroom veteran, Brennan celebrates ‘the female eye’ and is herself an amateur artist. She worked at Sotheby’s for 15 years before jumping ship to Christie’s. Her appointment reflects Christie’s conviction that America is the future, according to a senior executive at one of its competitors.

A 16 per cent plunge in auction sales to $4.2 billion in 2024 was partly offset by significant growth in private sales, which rose 41 per cent to $1.5 billion, the second highest in Christie’s history, which suggests a growing interest in discretion and flexibility. Christie’s now holds fewer than 300 sales a year, down from a peak of 700. Last year it held 293, of which 136 were online only. Cerutti recently said: ‘If you want to sell an important painting, the question is not London versus Paris. It’s New York versus private sale.’

Indeed, private sales of $1.5 billion across all segments of the market last year accounted for 27 per cent of Christie’s revenue. In the luxury goods segment – handbags, wine and cars – Christie’s sold $678 million at auction, 12 per cent of its total sales. There are also Christie’s Ventures and Christie’s 3.0 for NFTs and digital art. A banking arm offers loans against collections.

[See also: How to avoid buying stolen art – and what happens if you accidentally do]

The end of the art frenzy?

Over at Phillips, Martin Wilson, an art lawyer who chaired the British Art Market Federation (BAMF), was the in-case-of-emergency-break-glass appointment as the auction house’s CEO last December, after sales fell 17.5 per cent.

His appointment reflects Phillips’s ironic failure to sell itself as a business. Mischievously referred to by some art-world insiders as ‘My Beautiful Laundrette’, Phillips was described by a 2023 Guardian article, which drew attention to its ‘parlous financial position’ at the time, as ‘heavily reliant on guarantees provided by two founders of a Russian luxury retail group’. The group in question, Mercury, is registered and headquartered in Moscow (it operates the TsUM store in Moscow, the largest luxury department store in Eastern Europe). Its Russian-born founders, Leonid Fridlyand and Leonid Strunin, are resident in Monaco and Cyprus respectively.

For its ownership of Phillips, Mercury Group acquired a majority through a Luxembourg-registered entity (completed in 2012) and later shifted the parent company’s registration to the British Virgin Islands – before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which Phillips has publicly condemned.

Wilson, author of the definitive legal textbook Art Law and the Business of Art, is the safest pair of hands when it comes to compliance checks. But can he usher in a new era at the firm?

Over at Sotheby’s, Charles F Stewart is looking increasingly like a survivor or saviour, depending on your point of view. The apple-pie-normal, buttoned-down New England ex-investment banker only began his saleroom career in 2019, when Patrick Drahi, Sotheby’s Franco-Israeli owner, brought him across from another of his businesses (telecoms firm Altice) to climb into the hotseat as CEO. Stewart’s appointment followed Drahi’s ill-starred decision in 2021 to install his son Nathan, 26, to run Sotheby’s Asian operations. The move preceded a 23 per cent crash in sales, down from $7.8 billion to $6 billion, the second fall in successive years.

If Christie’s is looking west, Sotheby’s is turning east. Last August ADQ, Abu Dhabi’s sovereign wealth fund, agreed to invest $1 billion in Sotheby’s, becoming a minority shareholder. Hamad Al Hammadi, ADQ deputy group CEO, said: ‘Our investment underscores our firm belief in the enduring value of Sotheby’s brand, market-leading platform and the ability of its management to execute on their growth agenda.’

The investment underpins Sotheby’s ambitions in hubs such as Abu Dhabi, aligning it with the emirate’s cultural diversification goals. In April, Sotheby’s high-profile exhibition of more than $100 million worth of rare diamonds, crowned by a 10‑carat blue diamond estimated at $20 million, at the Bassam Freiha Art Foundation on Saadiyat Island was rapturously received. The show included an array of ‘breathtaking’ diamonds.

‘An exhibition of this kind and scale on diamonds has never been staged before in the Middle East, and very rarely anywhere else in the world,’ said Katia Nounou Boueiz, head of Sotheby’s UAE. ’So it is exciting to mark our first public exhibition in Abu Dhabi in recent years in such an illustrious way.’

The other three big sale rooms are not content to pass up opportunities for growth in the Middle East, either. Last September Christie’s secured its first commercial licence in Riyadh, where it plans to open an outpost dedicated to modern Middle Eastern art, jewellery and timepieces, while adhering to cultural and legal limitations (so no wine sales). Last year Phillips brought its ‘Guido Mondani Watches Collection’ to Dubai’s MB&F M.A.D Gallery (Dubai Mall) ahead of a sale in Geneva – its first watch roadshow in the UAE. Bonhams runs regular sales targeting Middle Eastern art, often alternating between Dubai and London. None (apart from Christie’s) yet runs a permanent local saleroom, but each is enhancing its visibility and outreach, signalling a strategic commitment to Gulf‑region collectors.

While Christie’s enjoys backing from François Pinault via Groupe Artémis, Sotheby’s from Patrick Drahi and Phillips from Mercury Group, Bonhams is the saleroom most directly exposed to market forces. Ever since private equity firm Epirus acquired it for an undisclosed sum in 2018, the 232-year-old Bonhams has been busy revitalising itself. Besides enhancing its digital capabilities, it has also expanded its geographical footprint by buying regional auction houses: Bukowskis in Stockholm, Skinner in Boston, Bruun Rasmussen in Copenhagen and Cornette de Saint Cyr in Paris.

With more departments than any other auction house, from low‑value collectibles to high‑end fine art, Bonhams hosts more than 700 live and online auctions annually (Sotheby’s hosts around 250 live and online auctions). As Robert Brooks, the former owner and chairman of Bonhams who died in 2021 aged 64, would tell me, the house’s breadth of offering and wide spectrum of collector-buyers have long been among its greatest strengths. Today, Bonhams’ jewellery department has been the market leader in the UK for the past 13 years.

Last August Bonhams appointed Chabi Nouri, the Swiss-Iranian ex-head of Piaget watches (often noted for sporting fashion-forward ensembles such as an eye-catching emerald jump-suit). Before Piaget, Nouri spent nearly a decade at Cartier, and when announcing her appointment Bonhams stressed: ‘Nouri has enormous experience in the luxury field and will doubtlessly explore this area when she arrives in post.’

According to a spokesperson, Nouri’s experience of the luxury sector reflects Bonhams’ drive to supercharge its credentials in jewellery, watches, handbags, cars and wine. Meanwhile, it may still be trying to fluff itself up and apply a coat of gloss in advance of a possible $1 billion sale that Bloomberg first reported in February 2023, when the saleroom was in talks with JP Morgan Chase & Co.

There are some – such as Loïc Gouzer, ex-deputy chairman of Christie’s Post-War & Contemporary art department, who dismiss the crisis as white noise. ‘I think the resilience of the art market was pretty incredible,’ he says. ‘I was expecting way, way worse than the results that we’ve seen.’

[See also: How to avoid buying stolen art – and what happens if you accidentally do]

Those who know Gouzer might argue he would say that. The subject of a nearly 8,000-word New Yorker profile of 2016 headlined ‘The Daredevil of the Auction World’, he is credited with reshaping the art market with bold, themed sales at Christie’s and Sotheby’s – most famously ‘Looking Forward to the Past’ at Christie’s New York in 2015. These art events wove compelling narratives around artworks, with blockbuster results. Known for cultivating high-profile clients from tech and finance, Gouzer blended personal charisma with unconventional deal-making, often landing deals over surfing trips or through creative financial guarantees. While he unsettled traditionalists, his flair for theatrical marketing and appetite for risk helped redefine auction strategies, leaving a lasting imprint on how Contemporary art is bought and sold.

He identifies two systemic issues at play. Firstly, the post-Covid shakedown of the art market is reaching its dénouement.

‘I don’t know if it was a bubble,’ he says, ‘but it was definitely an exuberance. It was like a shopping spree. At some point you get saturation. That brought a lot of energy into the market, and pushed up some prices. But those shoppers are gone.

‘The second thing is China. Thousands of collectors from China arrived in the market, but then disappeared when they found they were not allowed to spend more than X amount of dollars per year outside China.’ (Chinese citizens are subject to tight controls designed to prevent capital flight.)

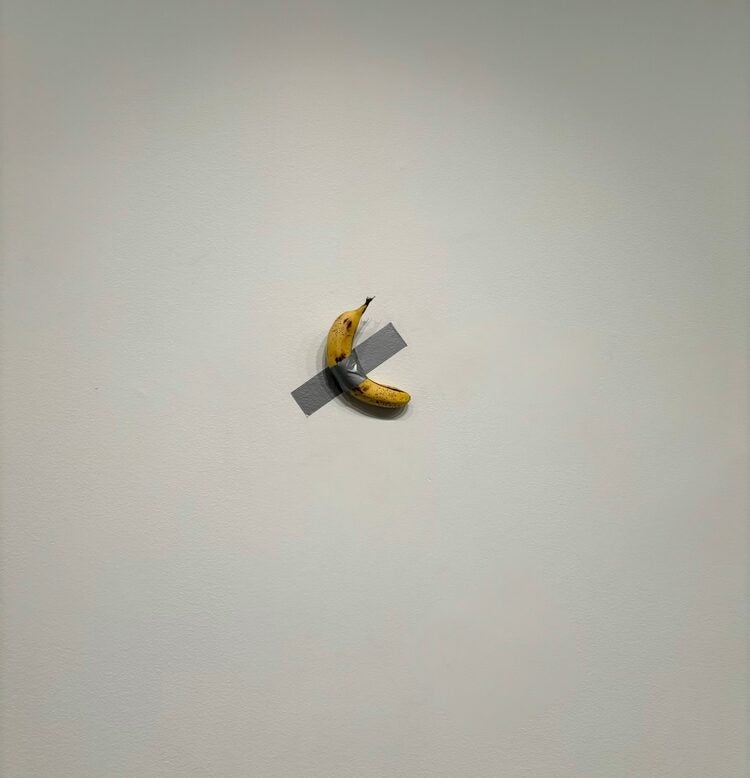

Gouzer believes the market must adjust to the diminished attention spans of an increasingly internet-fixated cohort of would-be collectors. But there is a question as to the sustainability of the quick-fix approach that has been adopted so far. Sotheby’s November 2024 sale of Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian (a banana duct-taped to a wall) hit $6.2 million. It was hailed as a coup, but this obscured the fact that ‘the rest of the sale was a disaster’, according to Christine Bourron, the French-born founder of London art market analyst Pi-eX. ‘Many of the lots didn’t sell. Everyone was looking at the banana.’

‘The way people buy art has changed,’ says Gouzer. ‘No one researches anything properly. It’s an ADHD way of buying. Normally, buyers study an artist, read books and go to retrospectives before they decide to start collecting an artist. Now people shoot first and ask questions later.’

Gouzer’s own art platform, Fair Warning, is an attempt to remedy this attention deficit. It sells just one work at a time, with not a banana in sight. Each art work stays ‘live’ on the app for two weeks and then is auctioned online.

‘Even when I ran Christie’s, we were having to devise strategies to catch people’s attention,’ says Gouzer, harking back to his imaginatively named sales. ‘If I Live I’ll See You Tuesday’, in 2014, was a tightly curated sale of cutting-edge Postwar and Contemporary works by artists such as Christopher Wool, Richard Prince and Jeff Koons. Its enigmatic title stirred curiosity and marked an irreverent departure from sober institutional language. Result: $134.6 million in sales. ‘Looking Forward to the Past’ (2015) was a cross-category sale that juxtaposed Modern masters with Contemporary artists. Themed like an exhibition, it challenged the traditional segmentation of sales. Its title name suggested time travel or conceptual overlap across eras. Among its lots, Picasso’s Les Femmes d’Alger sold for $179.4 million – a world auction record for any artwork at the time. Total sales: $705.9 million.

These auctions were more than about selling art. They were about storytelling, branding and making the auction a theatrical happening. Gouzer says his app, where only vetted buyers can purchase works, is conceptually a continuation of the same idea. It takes that minimalism to an extreme with just one artwork, one moment and one decision.

Gouzer says he is agnostic on what he will sell. ‘We only care about quality. That’s my driving force. I would love to auction a soccer player one day – the real ADHD market!’ I look forward to football players duct-taped to walls.

We have been here before. Gouzer’s approach has echoes of the auction of the collection of the late banker Jakob Goldschmidt at Sotheby’s in London in 1958. ‘One of the most radical aspects of the sale was having only seven lots – an act of veneration that was the very opposite of the wholesale tradition of auctioneering,’ writes James Stourton in his 2004 book Rogues and Scholars. ‘Attendees were asked to wear evening dress, unheard of for a London auction… The sale totalled £781,000, and at the end the audience stood up, cheered and clapped as if it were the climax of an opera.’

Now, in the summer of 2025, the owner of Grande tête mince is probably holding his head in his hands (in every sense) and reflecting on the curious irony that the work itself – ruthlessly reduced, stripped of ornament, honed to its brutal essentials – is a metaphor for the very market that rejected it. In its lean, unflinching form, Grande tête mince reflects a moment when the art world is slashing excess, rejecting the decorative and searching only for what is essential and vital.

This article first appeared in Spear’s Magazine Issue 96. Click here to subscribe