The fanciest, most traditional Japanese restaurants are more exclusive than any St James’s gentlemen’s club. Oliver Thring speaks to leading chef Kunio Tokuoka, who is trying to change all that — sort of

ONE OF THE most common complaints that foreigners raise against Japanese food is its perceived impenetrability: squelchy sea creatures, oddly sloppy roots and vegetables, disconcerting umami seasonings, the vocab. Things aren’t helped by the fact that traditional ryotei, or high-end Japanese restaurants, with their gardens, private rooms and giggling geishas, have tended to shun coarse and smelly foreigners. The traditional ones worked by invitation only and were populated mainly by businessmen and politicians being cooed over by geishas. Gaijin, or foreigners, went the received wisdom, sullied these dining rooms with their inexperience and vulgarity.

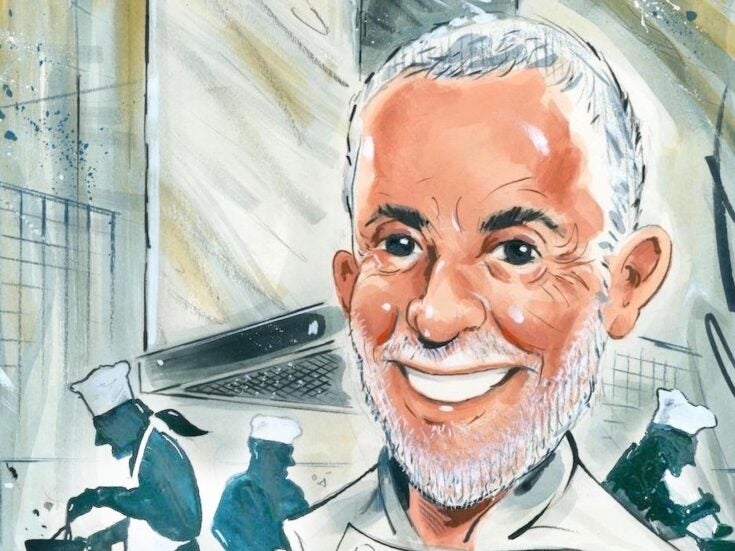

If things are now changing, this is in part because of chefs such as Kunio Tokuoka. He is trying to demystify elaborate Japanese food, both for Westerners and for his countrymen who might have never thought to try it. In his case, this has led to considerable success: Tokuoka’s group now owns six restaurants and a clutch of Michelin stars. He has been recognised by the James Beard Foundation, turns up at such sleb-chef jamborees as Madrid Fusion, and counts Ferran Adrià and Heston Blumenthal as friends. He is an ambitious and innovative restaurateur operating in the most formal, hierarchical and tradition-bound market in the world. Excepting Hollywood-ised expats such as Nobu Matsuhisa, to non-Japanese people who take an interest in restaurants, he is among the most famous chefs of all.

I visited one of Tokuoka’s high-end Kyoto restaurants expecting to speak to him there, but he got stuck in Tokyo, so we conducted our interview over the phone a few days later. His career as a chef looks inevitable, but it nearly didn’t happen. Tokuoka was born in 1960 to a well-connected culinary family. His maternal grandfather, Teiichi Yuki, founded a restaurant in Osaka in 1930. In 1948, Yuki bought a townhouse outside Kyoto and, over time, this developed into Arashiyama Kitcho, now one of the most famous ryotei in Kyoto. The ancient imperial city is known for producing the most elaborate food in Japan, especially kaiseki: tiny morsels spread between a dozen or so courses, full of rote, rules and ritual. By the Eighties, when Japan’s economic power seemed unassailable, kaiseki had grown flourishes of almost Neronian excess: single meals running into thousands of dollars a head, huge quantities of gold leaf, the money trickling away like the fountains outside.

The young Tokuoka had wanted to become a drummer in a rock band, but his parents had other ideas. So he went to live with a Buddhist monk who ‘had a fresh outlook on things’, as he puts it, hoping that the monk might persuade his parents to let him become a musician.

‘I meditated a lot,’ he tells me. ‘Sometimes I would fall into a trance, while cutting up wood for example, and I’d start to cry and tears would fall down my face. At last I realised that through my dogged desire to become a musician I was making everybody suffer, I was troubling my family, the monk, even myself.’ Tokuoka had always idolised his grandfather. ‘I thought again about him and how close I wanted to be to him, so I eventually decided that, on the condition that I would be able to learn from my grandfather directly, I would enter the culinary world.’

He did so, and his ‘utter love’ for his grandfather meant that he continued the traditions and the style that had made Arashiyama Kitcho famous. Everything changed after the bubble burst in 1990. ‘I saw then that what was unnecessary in the world would be cut out. I saw many companies and restaurants go bankrupt, and I realised that I needed to pursue Kunio Tokuoka rather than Teiichi Yuki.’

In part, this meant opening up the restaurant to newcomers. ‘In 1990, the grandes maisons and ryotei of Japan were all mysterious, covered under a veil. You never knew what was going on in them and they were hard to access from a customer’s point of view. I needed to disclose more information. I was one of the first Japanese restaurateurs to build a website for the business.’ He also opened other restaurants that pioneered a more relaxed, less forbidding style of dining.

IN TIME, THIS paid off. Two of his Kyoto restaurants now have Michelin stars: three for the mothership and one for its sibling Hana Kitcho, which I visited. Tokuoka also has restaurants in Nagoya, a gourmet snack outlet in Kyoto railway station and a bento joint called Shokado. In 2010, he opened his first restaurant outside Japan, called simply Kunio Tokuoka, at the Resorts World Sentosa in Singapore. This is one of the most expensive restaurants in the city-state. Customer feedback has been mixed in online forums, and a reviewer for the Business Times declared that ‘the cooking is good but hardly exemplary’.

In Kyoto, I’d naturally wanted to visit Arashiyama, but they told me this would be impossible for just one person. Since dinner for two there starts at JPY84,000 (around £650), before drinks, I reluctantly had to pass. Instead, at Hana Kitcho, I enjoyed radish pickled in beer, fried fish skin, hard Asian clams, anago eel, salted entrails of sea cucumber and sperm of the poisonous pufferfish, fugu. Lunch cost a little over £200. The dishes looked beautiful without exception, but the flavours were often more interesting for their balance, their lightness of touch and — at least to me — their novelty than for any discernible mastery in their cooking. There was frequently a tendency to put a couple of sea creatures on the same handmade plate, add a garnish of a budding twig or a flower, and send it out.

Of course, I’m just a typical uncouth foreigner. Perhaps I’d have understood the man and his food more if I’d visited Arashiyama, but that’s where Tokuoka’s talk about making his restaurants more democratic starts to wobble. The food is only a part of what customers pay for.

‘At Arashiyama,’ he says, ‘we have a traditional garden and tatami mats that are more than 100 years old. A lot of our plates and dishes are more than 400 years old.’ Someone has to maintain those gardens, pay for the kimonos of the (exclusively female) waiting staff. This is all part, I suppose, of the cosseting and potentially intimidating nature of the serious ryotei, and it requires something of a reassessment of Western priorities.

Even when they knew I’d be writing about them, they wouldn’t budge on letting me eat there alone, or consider offering a shrunk-down menu if I paid for someone else. ‘Some dishes come on large plates and you would choose several dishes from there, and presentation is part of the food, and that’s why we need to have the minimum of two people.’ Fine, but surely you could adapt things? ‘We would feel bad asking for the customer to pay as much when we wouldn’t be able to provide the right presentation.’

The polite Japanese inscrutability returns. For all that Tokuoka admits he is now forced to open his restaurants to Westerners because ‘the Japanese market is shrinking’, and for all that he has plans to open an outpost in Napa Valley, his most famous restaurant continues to adhere to the dogma and tradition of its ancestors. I’m sure that could be a positive and enriching experience for those foreigners who surrendered to it, but it does require a change of mindset.

Read more by Oliver Thring

kitcho.com/kyo to/english/index.html