Still Waters Runs Deep

For the past 40 years Alice Waters has led a revolutionary campaign to change the way Americans produce, consume and think about food, from the ground up

A HOT, SUNNY day in Berkeley, California. This city rests on the shores of the San Francisco Bay, a liberal turf of universities and gentle suburbs with pretty detached houses surrounded by lawns and trees. It is on one such suburban street — which actually feels more like a village — that Alice Waters lives. Her name has the greatest resonance in the United States, as it does to foodies in the know in the UK and around the world.

I chat with her in her garden under the shade of a vast and ancient redwood. We sit on quaint garden furniture sipping green tea and eating fresh apricots. And as we talk I realise that this is one of those meetings one occasionally has in life. It’s not just an interview, a question-and-answer session (although it is for her). For me it is an important moment in my career of thinking, writing and digesting food, for Waters is probably one of the most important voices in food in America. Her name will live on in the same way Elizabeth David’s has on this side of the pond.

She is a revolutionary, a passionate arbiter for good practice in sourcing food, in selling it, in consuming it. And her quiet voice belies a seminal importance that is every bit as magnificent and seemingly eternal as the great redwood that soars above us.

Waters opened a restaurant in Berkeley in August 1971. Called Chez Panisse, after a character from an old French movie, it served simple French food sourced from local suppliers. In the days, months and years that followed, as Waters focused on securing supplies from local producers, a whole network of organic farms and ranches grew up around the Bay area. She used local and seasonal food before it became a glorious cliché, and many of today’s biggest names on the US food scene either worked in her kitchens or were influenced by the food that came out of them. She challenged the pervasive influence of the fast-food business.

CLASS WAR

Today I wonder if she’s calming a little. She’s not, of course. Her latest mission is to persuade the government and other powers to provide children with free school meals — at breakfast and lunchtime, and an afternoon snack.

‘It seems to me,’ she says, ‘that if we change the criteria for buying food for public [ie state] schools we could potentially change farming overnight.’ Too many American kids bring junk food to school in their backpacks, she feels, and ‘there is no question that if kids are better fed — have a proper breakfast and lunch — they perform better’.

She wants farms to sell food direct to school, with no profiteering middle men. Though this may seem an expensive proposition, she is unequivocal: ‘Food can never be cheap. But I want to pay the farmer. I love and treasure the farmer. Carlo Petrini [the founder of the Slow Food movement] says that farmers are the intellectuals of the land. They are the stewards of the land.’

Of the farmers who are mass-producing food, the kind one might not exactly describe as intellectuals, ‘They are simply pushed into that direction because of the insecurity of the market,’ says Waters. ‘If you pay farmers the right amount and encourage those who are doing the right thing then we can bring them out of the woodwork.’ It’s an argument that Waters believes she has proven over 42 years of operating Chez Panisse. ‘We started buying from farmers and paying them a real price and they started flocking,’ she says. ‘Now we depend on them and they depend on us. It’s something really beautiful.’

I ponder the question of health and safety. I can imagine a situation, certainly in the UK, where local councils would object to small suppliers selling food directly to schools. Could they survive the rigours of Ofsted inspection?

‘I think the safety is in knowing your farmer,’ she explains. ‘Nothing is safer than that.’ The dominance of the food world by multinationals and their junk food, she adds, ‘discriminates against people by making them eat food that is not good for them’.

Good food, she says, is not elitist. ‘It’s not elitist to eat a ripe apricot,’ she says gesturing to the pretty pile on the table. ‘It’s elitist to talk about cooking with truffles, but not to talk about ripeness, seasonality and taste.’

Waters’ mission is to capture the minds of children, to make them appreciate food and to want to become farmers. ‘We have to get to the children first,’ she says gleefully. ‘We can teach them about affordability and stewardship. We need to introduce food in kindergarten, they should be taught to count with fruit, to draw pictures of food, to cook in dramatic arts classes. Food is fundamental to life, fundamental to the life of the planet, and there is nothing more important than to teach that.’

In the same way that schools had to introduce physical fitness into the curriculum, so they should with food. And how is she going about her campaign? ‘I have a lot of strategies — they might sound like pie in the sky but I can’t help myself,’ she says. ‘And it’s tough because the fast-food industry has a pile of money and they’re lobbying in an outrageous way, they are influencing congressmen and senators and it’s really frightening.’

While Waters wants to start things at the grass-roots level, she also has friends in high places. ‘Michelle Obama is somebody wonderful,’ she says, and of the president, ‘we know each other pretty well.’ She saw Barack Obama for a few minutes recently. She just kept repeating three key words to him: ‘Free. School. Lunches.’

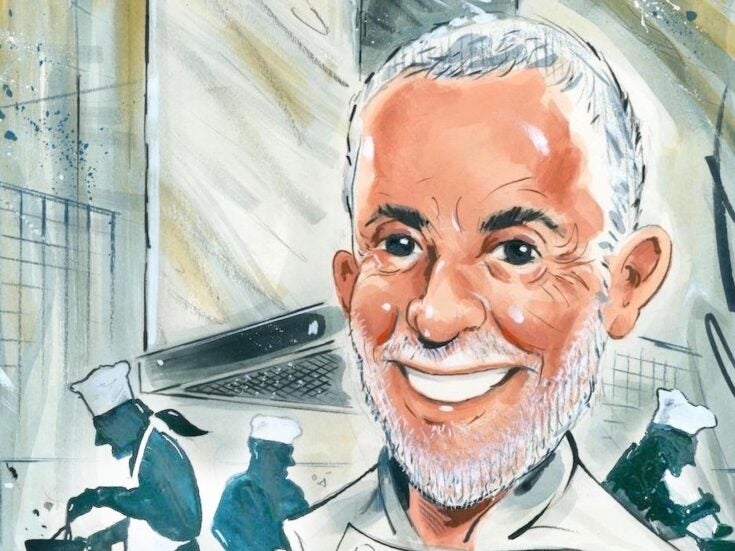

Photograph by Gilles Mingasson

JUNK FILTER

The culture of fast food, she observes is ‘pretty dismal. And when you eat it you think about the world differently. You want the same thing every time and wherever you go. If your mantra is fast, cheap and easy, you miss out on the important things in life. How can we be spoiling nature when it’s nature that feeds us? We know the train is going over the cliff and we have to stop it and get out.’

An artist friend of Waters recently did a cartoon of her. It’s Waters as a very old lady standing with a stick in a big supermarket. Strapped to her body are explosives and her speech bubble reads: ‘If you don’t go organic I’m just going to let it blow.’

The powerful controllers of the fast-food industry seated in their steel towers and concrete edifices homogenising the world with their burgers, fries, cartons of coffee and sugary, salty snacks had better watch their backs. This quiet lady in her pretty little garden is coming for them. And you’d better believe it.

Read more from William Sitwell

Don’t miss out on the best of Spear’s articles – sign up to the Spear’s weekly newsletter

[related_companies]