Appropriately, I was looking through photographs when I had the lightbulb moment. This was a few months ago. The Last Party, my book about the vivid club culture that was born in Manhattan in the late Seventies, went global and sputtered out in the early Nineties, was to emerge as an ebook, so I was working my way through… well, let’s say a mound of hugely evocative photographs. Some of the images have become embedded, like Rose Hartman’s Bianca Jagger astride a white horse in Studio 54, Bob Gruen’s John Lennon serioso with arms folded in a New York T-shirt and William Coupon’s broody Jean-Michel Basquiat. Mostly, though, they were fresh, surprising.

Here was a shot of Andy Warhol with a giddy grin — and how often have you seen Warhol grinning? — as he re-enacts having had a pie thrust in his face by the Yippie Pie Man, Aron Kay. That’s by the British photographer Mick Rock, as is the shot of the ultra-urbane novelist Gore Vidal alongside a punk with eyes like black glass, Stiv Bators of the Dead Boys. Or take in Marcia Resnick’s tableau of Mick Jagger and Andy Warhol (yes, him again), dining with William Burroughs in the writer’s space on Bowery. Warhol and Burroughs, fine, or Warhol and Jagger, OK. But as a threesome? That seems specific to those years of sociocultural collision.

Pictured above: Mick Jagger chows down with William Burroughs and Andy Warhol, as captured by Marcia Resnick in 1980

Then there are the clubscapes: Anton Perich’s shoals of faces beyond the velvet cord at Studio 54; Gruen giving the exterior of CBGB the look of a punk western; his Mudd Club seeming like a deserted gun emplacement. Collectively, these images suck anybody — whether you were there, or you weren’t but wish you had been, or (especially, perhaps) if you weren’t yet on Planet Earth — down a wormhole into a recent but breathtakingly different time.

And the lightbulb moment? Clearly there was a show to be done. Whitebox, an art space on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, agreed. I set to work.

The above-mentioned pics are all in it, but it was clear from the start that photographs would only be one element. In the book the story could be told in photographs. But putting a show into a four-wall space would let me cast my net wider, to include video, fashion, painting and performance, because the explosion of club culture was a story of tremendous social change and an art story too.

As to the social change, that is the forte of photographers, and it is they who record how early it was in terms of today’s celebrity culture. There were hostilities, of course, and the show includes Ron Galella’s gleeful picture of himself, the Prince of Paparazzi, lurking football-helmeted behind a pained-looking Marlon Brando (who had punched out five of his teeth the year before). Other Galellas include his bleakly reproachful Bob Dylan and, most relevantly, the dustbin lid heading in his direction, propelled by the hefty throwing arm of Elaine Kaufman. Incidentally, just before her death the restaurateur Kaufman told Harry Benson, the great Scottish photographer also represented in the show, that her two great regrets had been throwing Truman Capote out of her restaurant — he never went back — and chucking that lid at Galella. ‘She knew he brought some buzz,’ Benson says. ‘She liked the drama.’ Innocent times, though, before the trolls and player-haters swarmed, before celebrity ensured envy and rancour.

Pictured above: The Last Party exhibition

Photographers come to the story of Nightworld from different directions, though. A handful were photographing the life they were also living, like Billy Name in Warhol’s Silver Factory or Resnick, who had been making — and publishing — photographs that functioned as Conceptual art, until she was sucked into the life of the clubs, which she began to document with equal intensity. Or Wolfgang Wesener, who was one of two photographers working full-time for the club Area. For most of the photographers, though, the clubs were simply an available terrain, a social war-zone, with rich pictorial pickings. It was different for the artists, and here comparisons with the immediately earlier generation are relevant.

The hippy movement was fertile visually. Mags like Zap Comix, Oz in London, the San Francisco Oracle and the East Village Other published R Crumb, Victor Moscoso and Martin Sharp, and rock posters and album covers were vigorous forms — check out Storm Thorgerson’s images for Pink Floyd’s Saucerful of Secrets and Led Zeppelin’s Houses of the Holy. But was hippydom into fine art? OK, Peter Blake and Richard Hamilton were brought in by the Beatles to do album covers, as was suggested to Paul McCartney by the dealer Robert Fraser — but the artists were each paid £250 for their work, which indicates that this was not seen as a significant commission. The mighty counter-culture of the Sixties paid little attention to the small, intense avant-garde. And vice versa.

Pictured above: Hubert Kretzschmar’s cover for the Stones’ album ‘Some Girls’

This was absolutely not the case with the club culture during the Last Party years. There were similarities: such feisty pieces in the show as John Holmstrom’s graphic from Punk magazine would have been completely at home in the counter-culture of yore. So too the nomenclature of the Club Kids — Sticky Vicky, Kenny Kenny, Anita Cocktail — and the inventive invitations supplied by Michael Alig, who has a painting in the show and who embodied both the highs and the lows of the club culture. At first, his painting in the show looks Minimalist, until you realise it’s a pill. Under the influence of such pills he killed a dealer — a crime memorialised in the movie Party Monster. He served seventeen years, five of which were spent in solitary, during which time he began to paint. He did the crime, he did the time and he belongs in the show — not because of Mansonoid celebrity but because he confronted it, and because his over-the-top parties used kitsch celebrity as raw material in a way that brings to mind the Italian Conceptualist Francesco Vezzoli.

The cards created by gangbangers in Chicago will elicit a similarly complex response. They sport such greetings as ‘Compliments of the Almighty Satan Disciples’ and ‘You Have Just Met a Member of Silent Rage’, along with such motifs as top hats and Playboy bunny logos. But these cards also demonstrate an under-known chunk of cultural history. Graffiti, namely lettering and images made with spraycans, has become such a ubiquitous presence that we see it as a natural pictorial language, as generic as hard-edged abstraction. The Chicago cards — the gothicisms, the feudal language — suggest otherwise. The fact is the graffiti look which is now a global presence was born and developed in New York. There is a strong piece in the show by one of the principal forces in its development, Phase 2.

Picture above: Mike Cockrill’s poster of JFK

Painting, sculpture, drawing were very much part of the club culture, but it would usually be art bristling with the attitude of the Lower East Side

galleries which had been set up in opposition to the imperium of Soho. Alfredo Martinez contributes a diagrammatic painting of a gun on hand-made paper and a brutally powerful tribute to Basquiat; work by Henry Jones includes Soul City, an animated film of the rock band the Fleshtones, which Jones made by hand from cut-out photographs between 1977 and 1979, a couple of years before the launch of MTV. Rick Prol, Curt Hoppe, Walter Steding and Mike Cockrill catch the unruly mood, and Cockrill’s poster for his book The White Papers, a vivid drawing depicting the assassination of JFK, has lost none of its power to appal today.

It speaks to the cultural melt that accelerated during the years of the club culture that Steding and Cockrill are both also working performers. Michael Holman, who played in Basquiat’s band, Gray, has art in the show, including a video of Basquiat making graffiti. What this indicates is not just the vigour of the club culture but also that the art world had become so large, so powerful, that it simply could not be ignored as the hippies had ignored it. Indeed, Eric Goode’s club Area was essentially an art-themed club. The land artist Michael Heizer dunked a rock on to the dance floor and Warhol ‘installed’ one of his more Conceptual pieces, his Invisible Sculpture, there. (It was, yes, invisible.)

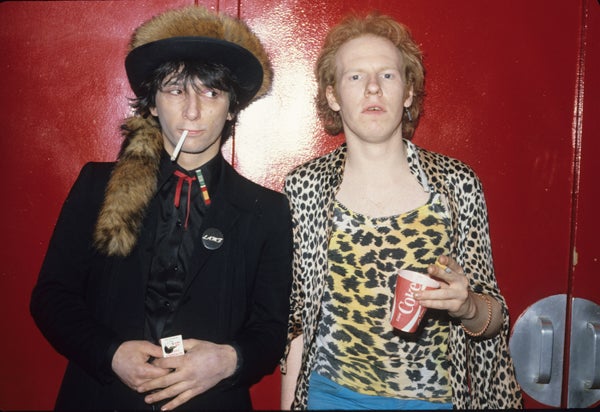

Pictured above: punks Johnny Thunders and Cheetah Chrome

Nightworld also morphed into a useful venue for ambitious younger artists. Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf and Futura 2000 all frequented Club 57 on St Mark’s Place in the Lower East Side in the later Seventies and early Eighties. Francesco Clemente painted murals for Palladium, the club on Union Square which Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager opened after emerging from the slammer for tax-evasion charges at Studio 54. And Basquiat made two paintings for the club’s Michael Todd Room. Indeed, he tried to sell them to Rubell for $50,000 each. ‘He said he needed the money,’ Rubell told me, adding dolefully, ‘I should have bought them.’ I found this info on an undated typed sheet but logic suggests that I must have written it between 1988, when Basquiat died, and Steve Rubell’s own death the following year. So it was whoosh! Down the memory hole again.