Philanthropists have the luxury of being able to think in the long-term – they can transcend short-term spikes of interest and concentrate on directing support towards interventions that work. But one such spike – the recent debate over ‘book banning’ in UK prisons – raises the question of how philanthropists can support prisoners on their path to rehabilitation.

Read more on philanthropy from Spear’s

In the article that sparked off the spike, Frances Crook of the Howard League for Penal Reform branded new rules to curb the number of parcels prisoners receive as ‘despicable’ and ‘nasty’.

The question of how to treat prisoners is always hotly debated, and it’s very important to get the answer right; but the two extremes of opinion could hardly be further apart.

Sheriff Joe Arpaio has prisoners at Maricopa County Jail living in a ‘tent city’ in the Arizona desert, while some of Norway’s prisons provide their prisoners with flat screen TVs and mini-fridges. Somewhere in the middle of the spectrum between retribution and rehabilitation, the ‘book banning’ debate is playing out.

The measures are part of a system of ‘Incentives and Earned Privileges’. By altering the allowances that prisoners are given to spend on items such as stationary, clothing, magazines — and books, the system aims to encourage prisoners to engage in what justice secretary Chris Grayling calls ‘proper positive rehabilitative behaviour’.

Deviation from the rules is similarly punished by taking away privileges. For this to work, prisons need to control the supply of these items, which means they cannot ‘be handed in or sent in by [prisoners’] friends or families unless there are exceptional circumstances’.

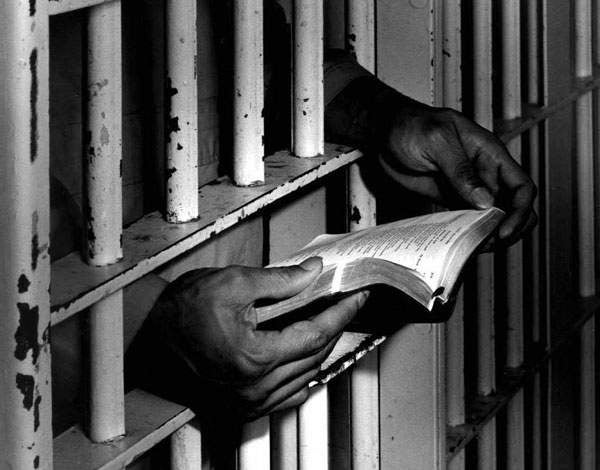

Grayling explains that access to reading material is not being curtailed; all prisoners can have up to twelve books in their cells at any one time and have access to prison libraries. Not exactly a ban, then.

Nonetheless, the debate does highlight an important point that warrants discussion. By making books part of a system of punishment and reward, you deny those that are punished — and therefore those that have the furthest to go in their rehabilitation — equal access to activities that have been shown to reduce reoffending and improve prisoner behaviour.

If, as a philanthropist, you’re interested in education as a rehabilitation tool, there are charities out there that have proven interventions. The Justice Data Lab’s analysis of 3,085 prisoners who received funds from the Prisoners Education Trust to buy learning materials and distance learning courses, for example, saw a reduction in re-offending of 5-8 percentage points compared to a matched sample.

There is a also a good body of evidence that supports the effectiveness of a whole host of interventions beyond education that can help to improve prisoners’ chances of avoiding reoffending.

This particular spike in public interest has of course had a positive effect in drawing people’s attention to the question of prison conditions and how they can impact quality of life and the likelihood of reoffending — supported in this case by an excellent body of research. But regardless of the spotlight, funding flows should always be determined, first and foremost, by need and the weight of evidence behind interventions that address it.

David Bull is a researcher at NPC