The future of the non-dom regime is firmly in the political crosshairs as the anticipated 2024 general election edges closer.

The Labour Party has said that it will replace the policy in the event of a victory, sparking fear among the UK’s 54,000 non-doms. Tax advisers have told Spear’s earlier this year that they are in the process of helping clients draw up ‘fire escape’ plans in case Sir Keir Starmer wins.

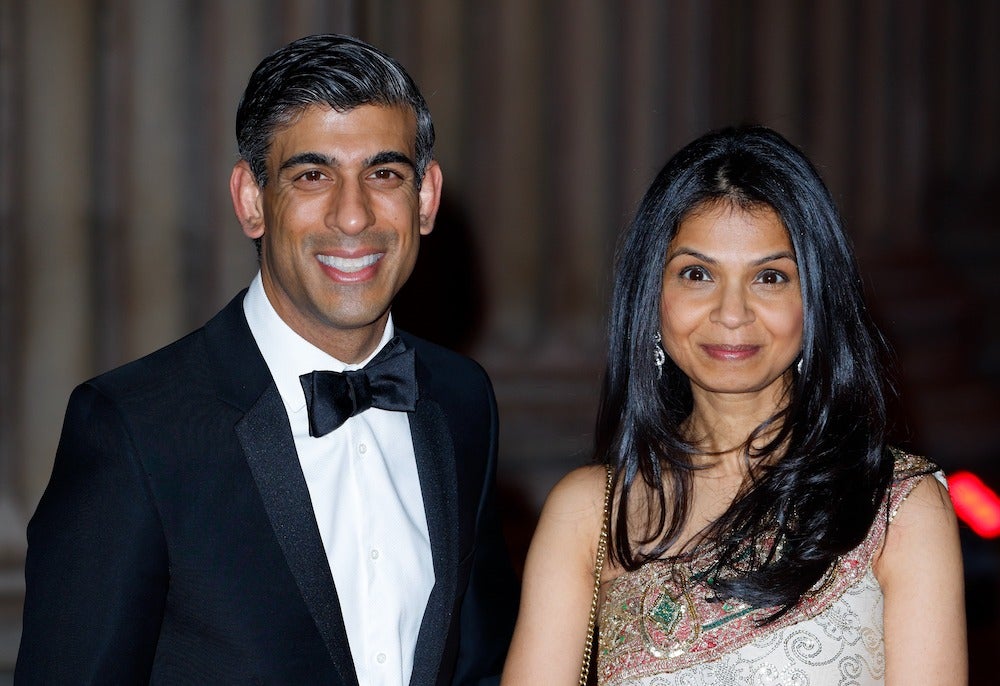

The Conservative stance remains undefined but the party showed its unwillingness to speak out in support of the policy after it emerged Rishi Sunak’s wife, Akshata Murty, had been taking advantage of the scheme. (This is no longer the case).

[See also: The UHNW non-doms leaving the UK to escape a Labour government]

So what can be done? In a new report, international law firm Withers has called for the existing non-dom regime to be dramatically reformed in order to make the UK more attractive to HNWs, while still ensuring they contribute fairly to the economy.

Christopher Groves, partner in Withers’ Private Client and Tax team, commented: ‘Does the current non-dom regime do enough to attract talented, entrepreneurial people to the UK? By any reasonable view, the answer is no. The whole system is ripe for an upgrade and our recommendations would make the UK a competitive, appealing destination for globally mobile families.’

The firm spoke to non-doms and their representatives to obtain a ‘first-hand view of where the current rules fail them and the factors that matter to them when considering relocating.’

The tightening of the non-dom regime

Non-doms currently benefit from the ‘remittance basis’, which means no tax is payable on foreign income as long as it is not brought into the UK. (The arrangement can include an annual charge, depending on how long a non-dom has been in the UK, of £30,000 or £60,000.) The Wealth Tax Commission has calculated that abolishing the scheme could bring in an extra £3.6 billion to the Treasury.

[See also: These multi-millionaires want you* to pay more tax]

HMRC’s rules have already become less generous for non-doms in the past 15 years. Changes in 2017 meant those living in the UK for 15 of the past 20 years are now treated as ‘deemed domiciled’, at which point they have to pay UK tax on their global income, as other UK-domiciled taxpayers do.

The numbers of non-doms have already started to fall. In 2008, 137,000 UK taxpayers were using the non-dom rules. The figure fell to less than 80,000 in 2018. Despite this, the tax take from non-doms and deemed domiciles hit a record level of £12.4 billion in 2022.

The threat of the non-dom exodus

A favourable tax regime is an important consideration for HNWs settling in the UK, but it is not the sole deciding factor, the Withers report notes. The quality of the British education system and the rich cultural landscape are also important.

As such, if the regime was to be scrapped, a significant number of non-doms would remain in the UK because of family ties, friends, education and other established roots. However, this favourable picture wouldn’t last in the long run.

[See also: Trusts continue decline as self assessments fall and HMRC bureaucracy intensifies]

HNW families might choose to remain in the UK in the short-term while children finish their education. Others might temporarily split, with the head of the family moving overseas to avoid being taxed, before being joined by their family elsewhere. Meanwhile, there would be some non-doms who would relocate immediately following a change to the regime.

Over time, the Withers report claims, the UK’s non-dom pool would diminish. More would slowly trickle out of the country and fewer would choose to settle. This loss of talent and capital would negatively impact the economy as well as secondary sectors that benefit from the presence of non-doms, like the cultural institutions supported by their donations.

When non-doms and advisers were asked for competitors, Italy, Portugal and Switzerland came out on top.

How to reform the non-dom regime

The Withers report highlights six key recommendations on how the non-dom regime could be reformed:

Qualification: ‘The link to domicile is an anachronism,’ the report says. ‘A new regime should be open to any individual who has not lived in the UK for the last 10 years.’

A higher flat fee: A flat fee of £100,000, which is competitive in comparison with other international regimes, would offer a ‘welcome move away from the complexity of the remittance basis’, the report claims. It draws comparisons to other popular destinations like Italy, which charges €100,000 a year from day one.

The report adds: ‘Non-doms appear to favour the convenience of simply making a lump-sum payment each year and some respondents considered this had the potential to convey a sense, publicly, that more of a contribution was being made.

[See also: Acceptance in Lieu: when offsetting inheritance tax is a work of art]

Use the system to encourage investment in the UK: The biggest issue for many respondents was the fact that money brought into the UK is generally taxed before it is invested. The report continues: ‘They felt that there should be some way of offsetting tax against investment (going beyond the current Business Investment Relief, which no one is particularly happy with), which would allow more investment to percolate through the UK.

Aligning with the visa system: ‘A new regime could be aligned with immigration policy so as to attract individuals along the lines of the current visa system, offering a preferential tax regime to Entrepreneurs, Innovator Founders, High Potential Individuals, Global Talent, etc.’

Time limits: Setting a 15 year limit to non-dom status, providing clarity for those who choose to remain longer term. Some respondents, though, suggested it could be shorter: 10 or even five years.

Managing the transition: The report notes: ‘By offering existing non-doms the opportunity to retain some or all of their current tax advantages after a new regime is implemented, the mass flight of talented individuals who currently live in the UK could be avoided, meaning they would be able to continue to contribute to the UK economy.’