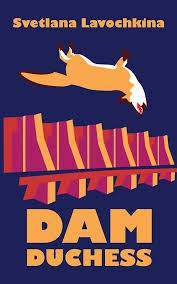

Omar Sabbagh celebrates Svetlana Lavochkina’s coup de force of a second novel – a work of ‘unfailing and pitch-perfect energy’

Ukrainian writer Svetlana Lavochkina’s brilliant second published novel, Dam Duchess follows swiftly on from her first, Zap (2017). The manuscript of this short, taut and zipping tale set in ‘Zap’ again (short diminutive for Soviet city of the Ukrainian republic, Zaporozhye) was runner-up in the 2013 Paris Literary Prize, much as Zap was shortlisted for the Tibor & Jones Pageturner Prize in 2015. Dam Duchess, far shorter than its predecessor, is however just as much a coup de force, and quite literally.

The one feature of the writing here which makes the novel tick and exhilarates the reader, is its unfailing and pitch-perfect energy. From the prose style in which the tale is written, managing to be both strident, bold and shorn of all ornamentation or redundancy, and yet still highly and colourfully poetic at the same time, to the plotting which connects and reconnects the small but sprawling array of equally colourful characters, to the deft building of world-space, with all the details of a bygone Soviet era rendered more than just real, rather hyper-real – this short foray, reimagining a smidgeon of the early Soviet era, is a page-turner that will satisfy at the same the high-literary purists in one fell swoop. Lavochkina, again, is able to be both a writer for the average educated reader who wants to be riveted and entertained and an experimentalist whose toying with craftsmanship is seamlessly, instinctually executed. Having now read both novels I don’t hesitate to say that the talent behind such writing seems to be both inborn and studied, eminently idiosyncratic and of real communal concern.

Across twenty-seven short chapters the tale unravels. I will not spoil the joy for the future reader by literally demarcating the plot, but only indicate here and there the way to my mind the writing succeeds, flourishes and with true aplomb. The novel starts with the sentence: ‘Iosif Viscerionovich Stalin fancied hydropower.’ That verb, playful and ironic, sets the tone for this macabre, blackly-comic story. After Mechanic Haim Katz is summoned, the ‘Great Helmsman’ sets him the task of superintending the building of the Dnieper Dam in Zaporozhye. We learn in the third paragraph that: ‘Of all the Bolsheviks, this Katz had made the most incendiary contribution to putting an end to the old way of things.’ And starting on this note is apposite to the (revolving) way the novel is paced. Part of what makes a successfully riveting narrative is this play between ending and beginning. Each chapter takes the story forward, but also unfailingly synchronises all the weird and wonderful happenings as part of one small unfolding world.

Haim Katz’s wife, we learn in an early backstory, head of Propaganda for the duration of the Zap Dam project, is a certain former aristocrat named Darya, the eponymous ‘Dam Duchess.’ Just as the action revolves around said limited heroine, Duchess of the honing of river-power for Soviet energy-projects, so Lavochkina is the mistress of her narrative rhythm, also releasing floods of energy from the way she controls its pacing. Dam Duchess would seem like an overall metaphorical conceit, whether intended or not. And to the technician’s eye what is so apparently successful is the way story and backstory intermingle and meld, world-building detail and plot-racing apace.

Here are three instances. In the first, and after the present action has opened dramatically, we learn in deft insertions of backstory both and at the same time of Katz and of the unified Soviet world-space rendered in this taut, sprung tale:

Katz had been quickly shown that gunpowder was much safer to handle than ten thousand proletarians gathered in one place, a volatile compilation from all over the huge ex-Russian Empire: peasants who ran away from forced collectivization and mandatory confiscation of crops; runaway felons seeking disguise in the crowd; soldiers of defeated Civil War armies, ruined merchants, petty nobility. Russians, Ukrainians, Poles, Mongols, Armenians, Finns, Tatars, Tajiks cross-breed in the dam nations’ crucible, creating gene mosaics hitherto unseen.

This kind of passage typifies the synergetic way a historical picture is drafted, which is a tableau at the same time highly pertinent to the literal happenings of the unique plot underway. In a similarly revealing manner, when the Dam Duchess (selling her sexual favours across the novel to all those who quite neatly take a ‘fancy’) has a certain Aaron Garlic put to work to produce for her a dress for a small but pivotal mini-ball scene towards the end, we read:

Aaron hauls the sacks further into his den. Disguised under a couple of blankets is a tailor’s dream. Aaron sniffs the silk, the taffeta, the wool, and bursts into tears.

Guard of hoes, robes, blankets, sheets, burlap saps, simple medicine, Aaron misses his vocation so much: he used to be the best tailor in Zaporozhye. All the nobility had their clothes sewn by him. He was the famous specialist for crinoline. Whether the Marshal, his wife or mistresses, or the Town Mayor, or the merchants’ wives – only Aaron Garlic was trusted to do the best job.

Even when dealing with subplots like that of the Romani gypsy camp on the outskirts of the Dam city project, the same technique of interweaving then and now, here and there, is at-work; and again, it simultaneously builds a picture of a world-space and details necessities for the current skein of events. The Romani man who will steal the Levi jeans, hanging on a clothesline, of Hugh Winter, the Dam-building American specialist hauled in by Stalin to oversee the Dnieper Dam, is introduced again before we zoom out to a brief and salutary wider focalization:

The Roma only have the clothes they wear – remaining naked when they wash it. The necklaces of 20-dollar American coins that once tinkled on their women’s necks dissolved, coin by coin, along the errant lines of the camp’s Europe-long itinerary. The golden Austrian ducats sewed up to their blouses and shawls were all long ago ripped out by the militia squads – swapped for freedom. Men’s chests house wind and snow, their leg hairs peep through the thin tatters of what were once called pants.

Another analogy which seams-up for the objective critical eye the inside and the outside of this tale, is the way that very world-building of the author’s, her configuring and making, her forging of the story is mirrored by the equally imaginative way in which many of these put-upon characters in the comically-rendered restrictive environment of the Stalinist Soviet Union, also make-do. Whether with serious or scurrilous intents, here are just two small examples. In the first, Aaron Garlic, another colourful character (detailed already) on-set and at-play around the construction of the Dnieper Dam, does his best to make a doll for Darya’s daughter, Mania, showing how now and then intermingle:

The dam stock clerk Aaron Garlic spent the evening combing the severed dark brown tresses, gleaning pearls after tiny pearls of dead louse eggs from each hair. He washed the redeemed locks in a bowl with industrial soap, poured a generous amount of hydrogen peroxide from the dam infirmary…. In a quarter of an hour, Aaron conjured up some bleached fleece, lifeless tow. He rinsed the locks in a zinc bucket… and poured a splash of sunflower oil into the bowl. He put the tresses onto a gray linen pillowcase. In the morning, he yielded a dry, long and pristine mane fit for a princess.

‘Yield’ indeed. Or later, with more rambunctiousness, Darya pays for the special supply of pre-proletarian music for her anachronistic ball-party which is also pivotal to how the tale ends:

For each item of real music, Darya paid Armaїs a special sex service he had pre-ordered. Backwards meringue for the Strauss, straddle split galore for the Strauss, the price of each further record unutterable without a shudder. The stunts were so difficult to perform against the throbbing background of sickness.

Just as in Zap – part of the same fictional world, that is to say – the near-mythic figure of Pushkin makes a pitting, repeated appearance like a leitmotif. Other literary figures who people the tale are Hemingway and Dickens, for example. Darya says at one point, like a puppet for that other Duchess, Lavochkina, honing the energies of her own river of plot and character:

“It’s English,” Darya said. “When reading Mr. Dickens back then, before all this happened, I thought he had laid the squalor too thick on the page. Now I wish I could kiss every sad passage in this book, so endearingly clean and cozy it looks to me now.”

Writing with more than native-flair in what is not her native tongue, English, Lavochkina breathes thrilling and macabre life into a small portion of a perhaps now-forgotten historical period. Indeed, a minor character, Rosa, one of many paramours put to use by Hugh Winter, including the Dam Duchess herself, is seen to describe in free indirect style the sight of a gramophone record playing with real impressionist verve, making, but without intrusiveness, character and author reflexive mirrors of each other:

With its diamond sting, a golden wasp meticulously licked lovely music off a stiff black pancake, always jumping up with a satiated burp before it touched the bright marmalade topping in the middle. Mr Winter had many black singing pancakes in his varnished cupboard, each sitting in a paper jacket with a round slot in the middle, to display the different sort of marmalade on each.

Later, Nikolai and Petro, two almost choric characters (also from Zap) of supposed Cossack descent, will peer-in at the fateful old-world-miming ball held by the Dam Duchess and her cohorts and compare the same gramophone record at-play, in bawdy dialogue, as ‘the tit of a negress!’ Throughout, thus, the characterisation is richly-effected; each token in the chess game of this little clockwork tale both coloured in unique hues and of a piece with the same hyper-real and macabre imaginary, commanding the lit, woken palette.

For any reader of literary fiction who wishes for a long afternoon of stylistic sparkle and a gilded element of old-world charm, bold and effortlessly colourful, Dam Duchess will startle and rivet as much as it will undoubtedly impress.

Omar Sabbagh is a short story writer and poet whose forthcoming book Minutes from the Miracle City is published by Fairlight