Rasika Sittamparam visits London Craft Week and peeks into the creative hinterland of some of the country’s most talented artisans.

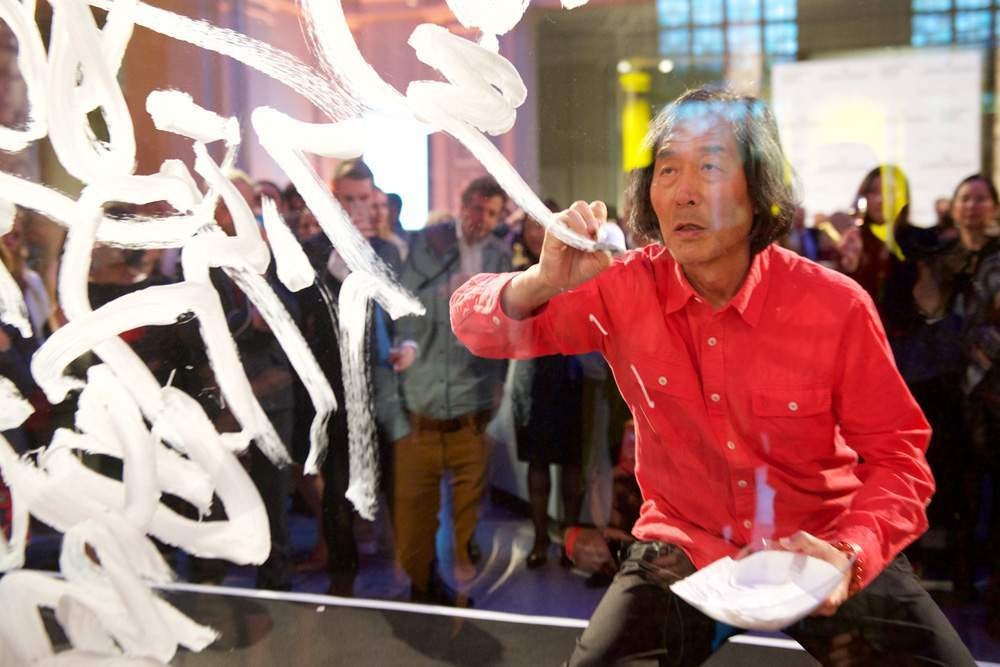

There was silence in the V&A’s grand foyer as Professor Wang Dongling took to the stage to stare intently at a two by three glass-like screen, brush in one hand and white acrylic palette in the other. The Professor then frantically dipped his brush into white acrylic and splashed it onto the screen (almost catching the smartly dressed audience in the process), before artfully gliding from one corner of the screen to another, leaving a trail of definitive but fluid streaks with feather-like edges.

It was the second day of London Craft Week 2016, a week-long festival to honour craftsmen. A grander return after its successful debut last year, the event kicked off on May 3rd, showcasing hidden workshops and demonstrations across London. There were opportunities to meet some of the world’s best craftsmen, designers, artists and jewellers, watch them in action and even try a hand at their craft.

Wang’s ‘live-art’ is a contemporary take on a 2,000 year old classic text by the Chinese philosopher Laozi. He portrayed a mad cursive script, an uninhibited form of calligraphy, traditionally done while drunk, although he executed it sober despite the event’s endless flow of champagne.

Ten or more minutes of dance-like movements, characters and incomprehensible symbols, later, Wang took a bow, thereby marking the festival’s official launch. Holding true to the week’s celebration of makers, the performance drew the impressed audience to the effort and process behind the piece (which was then donated to the V&A), giving the emotions and dexterity of the maker due limelight.

Clad in a simple red shirt, the artist’s humility and earnest smile belied the skill and balance involved in the task. The composure he took in maintaining a light brush for a nuanced finish was impressive. Like many craftsmen who spend hours, days and weeks perfecting their product, Wang demonstrated the fluidity of making, never stopping and never taking his brush off the screen, in what seemed breathless execution.

Wang’s performance made me think about the artistry behind craft and the endless debate of whether craft is art and vice versa. At Vacheron Constantin’s booth eye-catching watches were showcased, juxtaposed with the hands-on industry behind their creation displayed on large screens. The minute intricacies of watch-repairing, enamelling and designing were highlighted, with the makers striking a balance between engaging with the curious visitors and maintaining their clockwork precision connection of a myriad of almost microscopic components.

A Future Made, the exhibition I was at during London Craft Week, is a two-year collaboration between the New Craftsmen (whose founder Mark Henderson is a co-founder of London Craft Week) and Crafts Council – an organisation supported by the Great Britain campaign to promote British craftsmen abroad. Six of those craftsmen were bound for Design Miami/Basel’s Design Curio platform in Basel, featuring in an installation called Nature Labs – a visually intriguing array of objects created using traditional craft methods but utilising organic raw materials in an innovative way.

Why does craftsmanship warrant a week-long celebration? My visit to the launch of A Future Made gave me the answer as it allowed me to appreciate the creative process inherent in the art of an object. This is something that had resonance with the journey from the birth of a craft through to establishing its sustainability as a successful business and eventually helping talented craftsmen create an international repertoire via exhibitions and export opportunities. It is about the push needed to help young British talent reach international heights, and that is reason enough to celebrate.

The craftsmen were lively, flamboyant and proud, as they stood next to their projects. ‘You have all this thought and imagination,’ said Basel-bound Marcin Rusak, a young Polish London-based designer. ‘I feel the need to make things with my hand, otherwise you’ll go crazy – you need to have an outlet.’

Rusak, who has nurtured Art Nouveau craftsman ambitions since school, comes from an ancestry of over 100 years of flower growers. Inspired by his florist father, he works with unwanted blooms from flower shops, turning them into furniture, sculptures, jewellery and art. His work on display was a lamp made of a dark, marble-like, rod encased with subtly luminous cross-sections of flowers at various stages of life and decay. Despite its minimalist finish, the piece took almost eight weeks to make – a lengthy labour which involved collecting and drying flowers, casting them in resin and spinning the material into dark, onyx-like, details. Like insects resting in amber, the material captured delicate details of the captive flora. However, the identity of the flowers forming the gleaming streaks were a mystery, and, like abstract painting, remained ambiguous.

While flowers were one maker’s forte, another young artist drew inspiration from insects. Marlène Huissoud, a beekeeper’s daughter, shaped propolis (bee resin), using glassblowing techniques, into a glass-like hollow trunk. A designer who also turns silkworms into eco-friendly leather, the amiable London based Frenchwoman is a firm believer of the sustainability of the craft innovations displayed at the launch.

London Craft Week was also a reflection of UK makers’ thirst for evolution, combining traditional techniques with often overlooked natural substances. ‘What makers really want to be able to do is stretch and test and innovate and develop new ideas, new work, new processes,’ said Natalie Melton, New Craftsmen’s co-founder. ‘These [objects] are makers as alchemists, and that’s what we intend to capture,’ echoes Rosy Greenlees, executive director of the Crafts Council.

From the making of traditional luxury objects to the display of radical techniques to transform everyday materials, London Craft Week was about the talent, versatility and the passion of the makers, celebrating them as artists in their own right. There was a deeper meaning in Wang’s presentation. It depicted the first phrase from Laozi’s Dou, which describes the art of ‘transcending superficial qualities to seek harmony with nature’. Professor Wang apparently achieved this by integrating the philosophy of immateriality into a Perspex screen, which made me wonder if most craftsmen undergo similar meditations in the process of making.

The discussion of superficiality is apt, as the best of craft is often celebrated as high-end luxury, amassing exorbitant prices. But I couldn’t help but appreciate the genuine simplicity and earnestness of the craftsmen and women I met in the week, who seemed pleased at the opportunity to engage with the public after weeks and months of being buried in the complexity of their respective work and hidden away in rudimentary, remote workshops. It is a labour of love, the products of which are admired and deservedly held in awe.