Guy Sangster-Adams explores the arresting etchings of the celebrated artist whose animal-centric works question man-made ideologies.

An intriguing and serendipitous triangulation of Mayfair art galleries links Hugo Wilson’s two current solo exhibitions, Chroma Hunt and Rape of Europa. The former is at Shapero Modern and the latter a few streets diagonally north east at Parafin which early last year presented the artist’s first solo London show in ten years. The eponymous exhibition included a new group of paintings of strange, exotic hunt scenes in which the hunt is not with hounds but a whole menagerie. The paintings were inspired by the work of Old Masters, and in particular by Rubens and, as Wilson says, ‘with happy coincidence,’ days before his own opening, Rubens and His Legacy: Van Dyck to Cezanne, opened at the Royal Academy, creating the southern point of the gallery triangle.

Compounding the coincidence further the exhibition contained one of Rubens’ paintings that had been a very specific reference but which hitherto Wilson had only been able to look at online, Tiger, Lion and Leopard Hunt (c1616). There were also, as Wilson says, ‘incredible etchings and engravings of that work and others and I felt that the format and feel of them could absolutely be applied to the series of paintings I had just made’. So the Rubens exhibition contained not only one of the inspirations for the series of hunt paintings he had already completed but also the inspiration for the series of etchings in Chroma Hunt.

His first exhibition at Parafin featured works from across the breadth of his practice, as does his Rape of Europa exhibition at the gallery, and initially he envisaged that the etchings would be, he says, ‘a kind of break from that long series of sculptures, paintings and photographs which had been a two year project’. Before continuing, ‘but like almost everything I make it did not end up being a break but a year-long obsession…’

Not just an obsession, etchings are a passion for Wilson, ‘I adore them,’ he says, ‘I think they are the unsung heroes of art history’. He came to them, by his own admission, quite late compared to the other media he works in, whilst studying for an MA in Fine Art at the City & Guilds of London Art School eight years ago. He had previously received a classical training in drawing and painting during a four year apprenticeship at the Charles H. Cecil Studios in Florence, which he began after leaving school in 2000.

His motivation to seek a classical training began at the age of fourteen when, as he evocatively explains, ‘I saw a Tintoretto and it blew my head off! I got back to my Art GCSE and decided to start painting 20ft altar pieces; now the fifteen-year-old me wasn’t actually very good at this and so it became apparent to me that I should find someone who knew about it!’ In retrospect he is pleased that he undertook his technical training with Charles H. Cecil at a young age, an age when, ‘I really had very little idea of why I was making art, just an overwhelming need to do it’, before immersing himself in a lot of conceptual thinking and writing ten years later during his master’s degree.

The large amount of essay writing that the MA entailed lead Wilson directly to etching, in that he would often go and sit in The Engraving Room to write. While there the tutors slowly encouraged him to try etching and, he says, ‘I have been obsessed with it ever since’. Just as his classical training in Italy put him in touch with a direct artistic lineage to the Old Masters, so did the training he received in The Engraving Room, which provides, as City & Guilds of London Art School’s website explains, ‘an historical context of the intaglio process and offer[s] the same experience in terms of techniques, problems and solutions as that employed by Rembrandt, Goya and Picasso,’ and that their aim is, ‘to keep the bridge to the Old Masters open’.

That bridge is also one that Wilson very much keeps open in his work, exploring the breadth of its span, whilst cleverly and adroitly through his extraordinary technical ability keeping a foot on both banks mixing an ardent contemporaneity and desire to reflect the world of today with a deep understanding and passion for history. Both his original series of hunt paintings and the Chroma Hunt etchings are great exemplars of this, echoing the hunting scenes that were popular with wealthy collectors of the 17th and 18th century who saw them as powerfully primalistic representations of mastery over nature. But as one looks more closely one sees that Wilson has stripped away much of the detail of the hunters themselves, emasculating them and diluting any projection of the power or mastery of man to question man-made ideologies, while reasserting the power of the animals. In so doing he successfully deconstructs the context of the works he so artfully emulates.

This, ‘playing around with the context of older works,’ as Wilson describes it, is he says, ‘also perfectly suited to etchings’. His first series of etchings based on the hunt paintings were black and white, but Bernard Shapero, from Shapero Rare books the company that launched Shapero Modern, encouraged him to create four hand-coloured portfolios of the nine etchings – Chroma Hunt. ‘This was something new to me,’ he says, ‘I had a go and I started to really enjoy the result – it was an interesting process to take imagery from a coloured painting, then re-work it into a black and white etching and then re-introduce colour again’.

Wilson worked with specialists to create the etchings, Bernard and Sue Pratt of Pratt Contemporary, with whom he has produced all his etchings over the past seven years. The process, ‘really appeals to the obsessive nature I have,’ he says, ‘I do get fixated on the perfect umber ink or a certain Japanese paper,’ but equally he explains that he has a slightly different relationship with his paintings than his etchings, because with a painting he ‘can only see mistakes, areas of them that still upset me even years later, but with etchings because of the chaotic nature of how they are produced I feel kind of once removed from them’.

In explaining this ‘chaos’ he says, ‘each line or patch is made by acid eating into metal to create an area that holds ink, that ink is then what gets printed from the copper plate onto the paper that is presented, so whilst your drawing can be perfect there are so many factors that are outside of total control, this can be the strength of the acid, the quality of copper, the time of year or temperature, and all these thing add up to a process that can look exact but really isn’t. This lack of control is firstly good for me and has also fed into other parts of my work as you have to have the ability to work with accidents, as once something has been acid etched into metal, you can’t really remove it’.

Another facet of creating the Chroma Hunt portfolio was that Wilson liked the idea of ‘preserving the “bones”‘ of all the work that he had put into the paintings. ‘I felt that the imagery of the paintings that these works were taken from had been so hard fought to put together,’ he explains, ‘and really represented a breakthrough in my practice’. These breakthroughs and his arresting use of animals to express his themes continue in the excellent new paintings that are included in the Rape of Europa exhibition.

His portrayal of animals is as fascinating as it is captivating. All of his artworks are rooted in an exploration of the human need for ideology for a sense of fulfillment, and he explains that he uses animals for a number of reasons. ‘Firstly I want to nudge you into thinking that you have seen a lot of what is in my paintings before,’ he says, “but I don’t want to directly reference things too much, so for example if I have been looking at a great 17th century religious Italian work, I can often re-work the composition replacing saints with animals, or drapery with 19th century machinery or 1970s sci-fi film sets’.

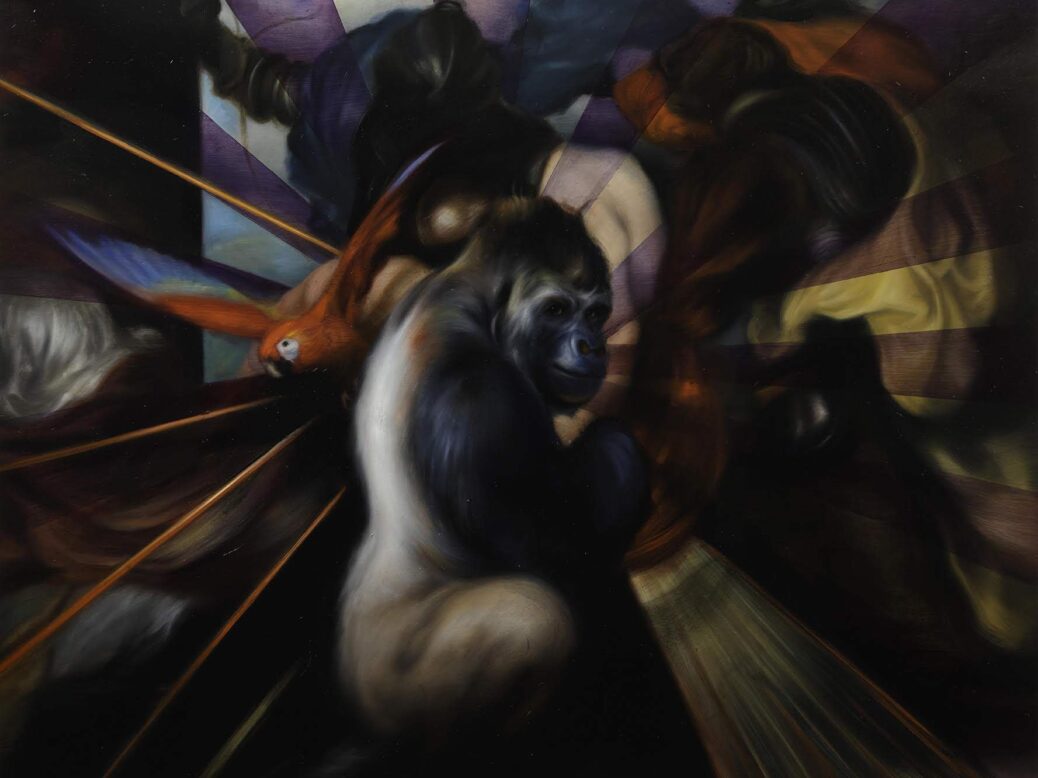

A wonderful example of the above in his current Parafin exhibition is the painting, Simian Disco (2016), which is part Baroque, part Barbarella, a mix of altar piece, stained glass window, and celebrity paparazzi shot. In which the centre-stage Silverback gorilla, regards the viewer over his half-turned shoulder, in the midst of swirling drapes and suffused radiant lights.

A simian regard catching, holding, questioning and challenging the viewer’s regard is a recurring theme in the works in both Wilson’s current exhibitions. ‘Animals help you play this game of empathy and recognition really quickly, as we always do this to them anyway,’ Wilson says, ‘I always attribute a human characteristic to an animal and once I have got you doing that in one of my works you are already playing the game I want you to with the rest of it – and monkeys and apes being the most like us are the best for this’.

The sense of play in Wilson’s work is a wonderfully engaging and powerful tool, enticing one to look longer and deeper at the works to enjoy their exquisitely executed, dichotomous celebration and subversion. He eloquently describes the contexts that he ‘messes around with’ all as having been part of the ‘theatre of the important’ at a point in history: ’16th century menagerie paintings, 17th century exotic animal hunts, or even pastoral English cows of the 18th and 19th centuries, all represent a past context that has been cemented as important by time and group decision – perfect for me to start messing around with!’.

With the rarity of two solo exhibitions running concurrently, within a few minutes’ walk of each other, Chroma Hunt and Rape of Europa, provide a wonderful and highly rewarding opportunity to relish the work of a hugely talented artist.

Chroma Hunt: Hugo Wilson

Runs until 21st January 2017

Shapero Modern

32 St. George Street

London W1S 2EA

Rape of Europa: Hugo Wilson

Runs until 28th January 2017

Parafin

18 Woodstock Street

London W1C 2AL