On the 50th anniversary of the Swiss sculptor’s death, this window on his Parisian existential orbit and his influence on British art provides a welcome celebration of his art, says Alex Matchett.

You do not quite get to post-war Paris via Norwich. However the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts’ latest exhibition, Alberto Giacometti: A Line Through Time, does take the visitor somewhere close: If not to the cafés and studios where the existential movement was discussed and rendered then to the mind space which created some of its most recognisable artistic inhabitants.

The exhibition is a celebration of Alberto Giacometti’s work in the context of post-war Paris and his subsequent influence on the British artists of the period. The line through time is not a strict chronology but a reference to the influences around him and his own role as a medium for the lean existentialist baton passed across the Channel.

Considering the transient parameters of the existentialist movement, the exhibition refrains from making its own abstract overtures. Instead it builds a narrative around Giacometti’s early works, his impressive paintings and his relationship with the Sainsbury’s before unveiling his stripped-back stick-men centre pieces — an odd chorus of individuals, too isolated to interact as a collective, harshly bared by Giacometti’s desire to detract. They intrigue as much as they haunt, impervious to time, blades in the wind, motionlessly cutting an existential silhouette.

That black hole is not dived into, although the angular flux of the Centre’s display spaces could well have tempted the curators to build a skewed mirror of the themes and art they feature. Perhaps more responsibly, there is a charting of Giacometti’s early sketches, full of whirring movement, and his portraits which are more reflective but no less living, the paint applied like the clay in his sculptures. On moving to Paris the ideas, or at least the fashions, of the time prove irresistible to his talent. He sketches ‘Paris sans fin’ and makes Art Nouveau furniture. He befriends artists and patrons including Robert and Lisa Sainsbury who can only persuade him to relinquish ‘unfinished’ sketches of their son David by providing Giacometti’s wife, Annette, with a raincoat.

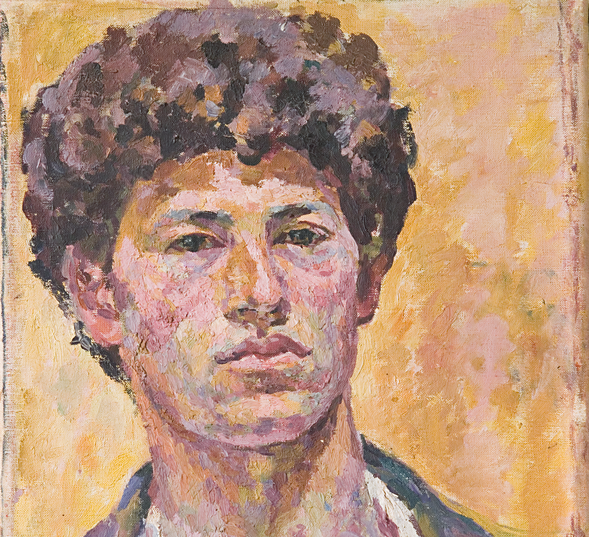

1948’s fiercely parsimonious sketch of Giacometti’s brother Diego is a marker of the post-war sculpture that became his signature. In the penultimate space we see these figures firmly placed inside the artistic flowering of the existentialist movement. They are joined by hallucinogenic mindscapes, surreal post-war departures and the existential wanton demanded by the horror of what had gone before. The physical and metaphorical loss of the person the war orchestrated is seen in powerful pieces such as Gruber’s ‘Nude Woman in a Landscape’ (1948) and Cesar’s industrial ‘Venus of Villetaneuse’ (1962). The uncomfortable starkness of these pieces give Giacometti’s sculptures, lined in the centre of the room, a warmth. Here is a hearth of meaning – the individual’s ‘being’ role enough to celebrate. ‘Diego in Pullover’ (1953) is a pinched head on broad sloping shoulders; it is a little bit lost and devastatingly human for it.

The curation allows the question on whether Giacometti retreated with his distinctive sculpture from a broader, more creative path. Sculptures such as the primitivist ‘Spoon Woman’ (1926) and the cubist ‘The Couple’ (1926-7) suggest so. Fittingly his primitivist influences and historical horizons are celebrated in a fascinating window of chiming art powered by juxtaposed chronology. Numbered among millennia-old Anatolian pieces are small Giacometti pieces, homages to his inspirations.

The final room brings Giacometti’s line to his British contemporaries. The forms and shapes he made rightly appear seminal to the British response to existentialism. The touchstone is ‘The Cage’ (1950), a boxed figure reaching out to the contours of their place and no more certain for it. The motif is now more known in Bacon, ‘The Cage’ sits by his ‘Study of a Nude’ (1952-3), but it is one the painter owed to Giacometti. There are other informed responses, notably in the sculpture of Paolozzi and Turnbull – almost extensions of the Swiss’ projects. The last room heavily references Herbert Read’s championing of British sculpture and what it owed to Giacometti’s artistic assertion that ‘size is not the same as scale’. The Waste Land is quoted and becomes inseparable from the tapestry, perhaps as London’s prologue to Paris’ modernist breakdown after the second act of war. A final highlight is Man Crossing a Square (1949). Finely nuanced in this setting, the geometry of the stride appears all the more sinister; it represents an existentialist freedom as terrifying as it is naked.

Like the impressively cosmopolitan Bacon show the Sainsbury Centre featured last year, this exhibition seeks to place its subject in a richly detailed setting. This is successful in illustrating the dialogue Giacometti took from artistic sources, and how that in turn spoke to his British contemporaries, but the purely artistic references make the existentialist labels heavy ones. The Bacon exhibition benefited from a glut of art to provide an, almost too, thick a forest of reference; the same cannot be said of this sparser, more measured show. However, like that exhibition, it does boast brilliant art works given a compelling framing with the Parisian existential narrative and its lean on our own artists.

The curators talk about making the Sainsbury Centre in Norwich a destination for art pilgrims. This exhibition will further brighten its beacon. Giacometti’s dialogue is given new context and, although the more human appeal of his sculpture is overshadowed, the humanity of the artist isn’t. Co-curator Claudia Milburn mentions Giacometti’s ability to stand outside of any definitive movement ‘with his own unique vision’ as well as his absorption of contemporary and historical artists and philosophers, notably Camus and Sartre. Fittingly A Line Through Time appears in conjunction with a superb display of Henri Cartier-Bresson photographs, some of which have found their way into this exhibit. In one we see Giacometti crossing a leaf-strewn Parisian street, huddled from the downpour beneath a raincoat. One wonders if it was the one Annette bartered from the Sainsburys, taken in the moment, to keep his artistic existence dry.

Alberto Giacometti: A Line Through Time and Henri Cartier-Bresson: Paris are on at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, Norwich until August 29 2016