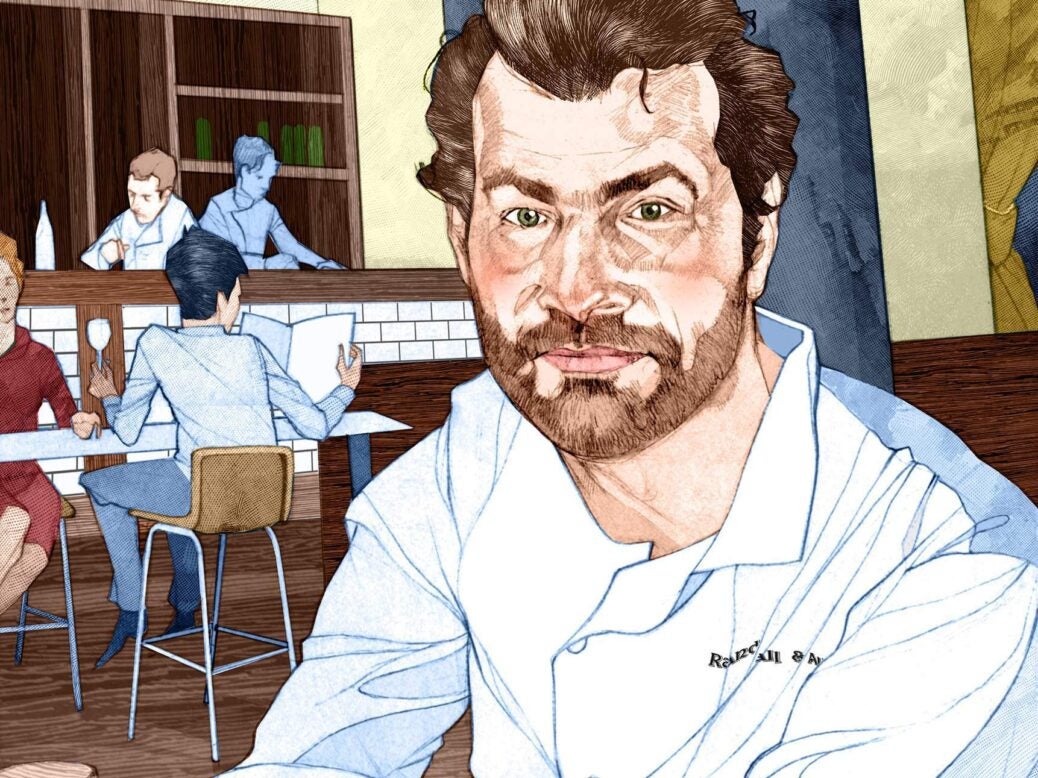

Ed Baines dived in at the deep end when he opened Randall & Aubin twenty years ago, but the seafood joint soon hooked London’s discerning diners, writes William Sitwell.

Ed Baines, restaurateur and chef (occasionally of the celebrity kind), is reflecting on his life while relaxing over an Italian lunch in Clapham. We are well away from the crowded streets of Soho and the hustle and bustle of his restaurant on Brewer Street, Randall & Aubin. He finds it strange to believe that it’s twenty years since he and business partner Jamie Poulton opened the doors to their seafood restaurant.

‘We were just two guys in our late twenties in the heart of Soho, opening a place and being completely oblivious to the demographics or where we were and whether it was what people wanted. We were just doing what we wanted to do,’ says Baines, now 48 and with a thick beard (he was once labelled, he helpfully reminds me, as ‘Britain’s sexiest chef’).

Baines and Poulton had been introduced in a pub at a time when the pair were coincidentally looking for a suitable partner. Ed, as a chef, needed someone who could do numbers, and Jamie, working in business, needed someone who could cook. They found an office in Soho and started to look for sites. Then, by chance, the old deli and butcher’s opposite closed and the pair were able to take on the lease.

Randall & Aubin had originally been founded in 1908; it was London’s first French butchery. The cookery writer Elizabeth David mentioned it in some of her books in the 1950s. It was where those in the know would buy rolled, trimmed and cut meats, and the likes of sweetbreads and other offal, rillettes of duck and sourdough bread. But their cork-lined fridges and meat displayed on ice on marble clashed with the health and safety mores of the 1990s, and Randall & Aubin reached the end of its original journey.

‘The business hadn’t moved with the times,’ says Baines, ‘and demand for exquisite continental food had gone.’ They negotiated a lease with six months free, on 1 August 1996 Randall & Aubin was born again as an Anglo-French brasserie and, says Baines, ‘it immediately filled up with prostitutes, gangsters and clippers’.

Baines had come from the refined confines of cooking at Daphne’s, the Chelsea haunt owned at the time by the Danish restaurateur Mogens Tholstrup. ‘I was confronted by a different element,’ he says of his new customers, ‘but our philosophy was to cook everything for everyone. At the time there was no place that did lobster and chips, crostini and pinot grigio.’ The seedier customers and what Ed calls ‘those endlessly laughing gangsters’ moved on, and the restaurant became, as he puts it, ‘the perfect place to either celebrate or drown your sorrows’.

Now, twenty years on, Randall & Aubin is a firm fixture of Soho, yet many are surprised that the concept hasn’t been rolled out across the country.

‘We have thought about it over the years,’ he explains, ‘but if you look at fish restaurants most of them have failed. You can only do a chain if it’s based on cheap things to roll out. You simply can’t do that with fish. The fish we sell is a natural wild food, a premium product. Look at the restaurants Richard Caring rolls out around the world… but he’s not rolling out J Sheekey [the seafood institution operated by Caring’s business Caprice Holdings].’

However, Baines does say there will be a second R&A opening soon in Manchester (with fish sourced from Whitby as well as local cheeses and breads), and he will spend three days a week in the city when it opens. It’s a city he got to know when, after Randall & Aubin opened in a blaze of publicity, he was asked to do TV. He hosted a daytime show with fellow chef Simon Rimmer and then graduated to his own series, Lunch with Ed Baines, in which he would cook while interviewing celebrities. Then came Entertain with Ed Baines on ITV. So by the late 1990s and early 2000s he was a successful restaurateur and a famous TV chef.

It was a satisfying place to be for a boy born and raised in west London. His father had a successful job at Fiat, and with two elder brothers life was, he says, ‘idyllic’.

‘My mother was so happy and a great cook,’ he reflects. ‘Our upbringing felt quite continental and there was always lots of pasta!’

But then, when he was just eight, his father developed leukaemia and died at the age of 38. ‘Our perfect setup was blown to pieces,’ he says. ‘Life became quite tough and my mother was emotionally blown away.’ But she was tough and inherited his father’s position on the company board of his car parts firm.

Baines later left school ‘very wild and thrust into the workplace’. He found a job at a patisserie (‘making cakes was quite odd for a former boarding-school boy’), but he found he had a talent. He worked in Europe, on boats — from France to Australia — did ski seasons and, after a stint at Bibendum, found a job at the River Café. The restaurant was ‘a ray of sunshine’, he says. At the time he was cooking with other future stars such as Theo Randall, Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall and Samantha and Sam Clark (now of Moro).

‘The late Eighties saw a movement of academic guys going into the food world,’ he says, talking of the likes of Rowley Leigh, Alastair Little, and Simon Hopkinson. ‘They wrote menus based on what was best available and in season.’

Fast forward to the early 2000s, and while business at Randall & Aubin was successful (‘millions of pounds were going through the till’, he says), Baines appeared to be enjoying the fruits of his labours rather too much. ‘I had adopted a sinful life,’ he says. He had also met his wife Anne (with whom he has two young children: Francis, six, and Harriet, four), who spoke firmly to him one day.

‘She sat me down and said, “Your life is not normal. You’re going to be obese, morose, and then you’re going to die.”’

Surrounded by what he calls ‘hedonists and maniacs’, he realised that it was not sensible to drink with his customers. ‘I now draw a firm line. Fun is for my customers. I cook in my restaurant but I don’t party there. As I get older I need to be in control.’

Today, as he eats a simple plate of pasta at a favourite neighbourhood restaurant, he considers the pool of talent in London. ‘There are too many chefs who think cooking is arranging food on a plate with tweezers. That’s not cooking. Cooking is what Marco Pierre White did as a young man. Make me a poivre sauce or a navarin of lamb — that’s cooking.’

Baines may not have rolled out his seafood restaurant — although as well as Manchester he is thinking about a branch on London’s South Bank — but he does also have a stake in a couple of pubs. ‘I’d rather have one full restaurant than ten half-full ones,’ he explains.

‘I was chatting to a regular the other day. He told me he’d first come to Randall & Aubin with his girlfriend. They were now married and today, with four kids, were celebrating the eldest’s fifteenth birthday.’ For Baines it was ‘a moment of pure satisfaction that you can’t plan, or put on a spreadsheet’.