Modern technology is helping to breathe new life into ancient manuscripts, writes Lucia van der Post

When, many years ago, in another life, I was a fledgling design journalist on a national newspaper, the word ‘repro’ was enough to make anybody in the world of design shudder. I remember a design guru of the day referring to the British people’s then strange affection for what he called ‘ruptured repro’ in the most disdainful terms. Those were the days of the design diktats. There were certain approved ways to design – pattern was looked down upon, modernism reigned, and American architect Louis Sullivan’s aphorism that ‘form ever follows function’ ruled the day. And ‘repro’ was looked down upon most of all.

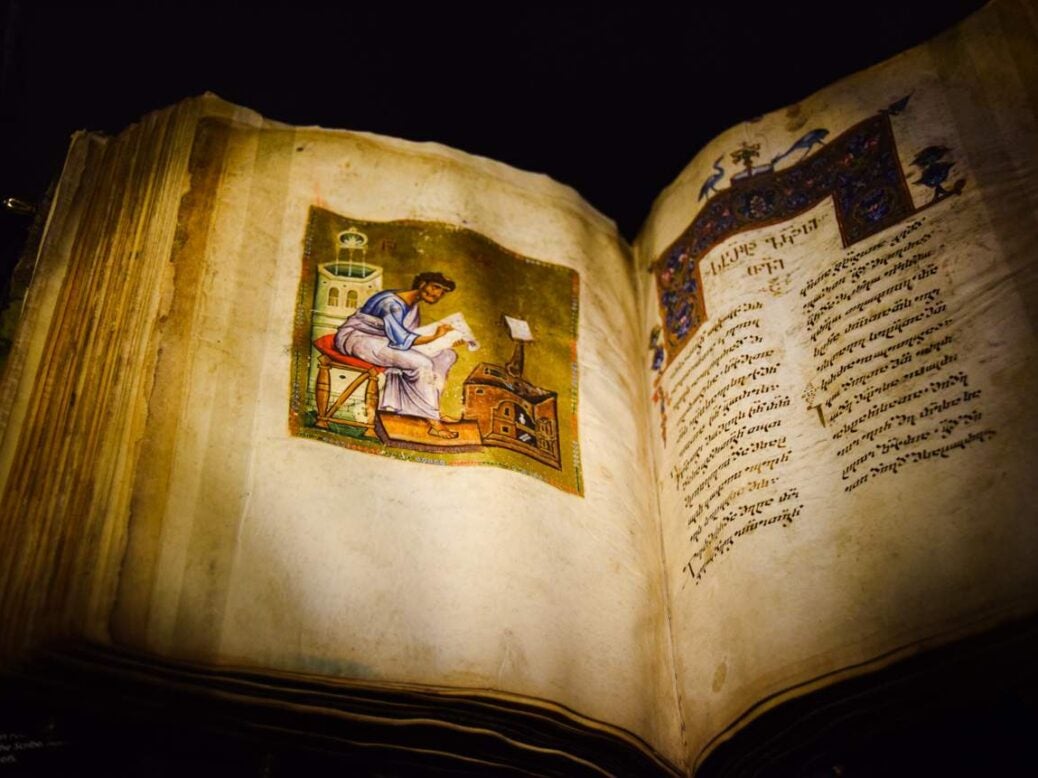

Here we are, some 50 years later, and some of the most extraordinary work is being done in the field of, yes, repro. Take Facsimile Editions. Founded way back in 1980 after Michael Falter, whose family had been in the printing industry since the late 1800s, looked at the manuscripts on display in the King’s Library in London and thought how wonderful it would be if he could study the whole manuscript at his leisure, instead of having to make do with just the two pages that happened to be open in the museum’s showcase. Now Facsimile Editions, which Falter set up with his wife Linda, has made exquisitely fine copies of some of the most precious manuscripts in the world.

They started off with the Bodleian Library’s Kennicott Bible, one of the most lavish medieval Spanish scripts in existence. It dates from 1476, is hand-written in the clear Sephardi script of the Middle Ages, was bound into a Morocco goatskin, but is most famous for its sumptuous illustrations. The Falters have gone to immense trouble to reproduce it precisely – paper is specially milled for each edition to replicate and capture the ‘feel’ of the original manuscript, while gold and silver metal leaf is applied by hand to raised and flat surfaces. For some editions, real vellum is used which is still made today in the same way it was made in the Middle Ages. Every detail of the original, no matter how small, is faithfully reproduced by craftsmen who are prepared to collaborate with the Falters in their quest for the highest quality.

Only 550 copies were made, of which there are still a few left for sale at £7,950 a time. Among the other beautifully executed facsimile editions on sale are the Dead Sea Scrolls (just 49 numbered copies were made, £49,500 each). The Falters also take on private commissions, often being asked to create books of family archives. Currently, for instance, they’re putting together a group of falconry manuscripts for the International Fund for Houbara Conservation, an Abu Dhabi-based foundation.

Meanwhile, Factum Arte is a Madrid-based company that is doing ground-breaking work. I came upon it when I joined an expedition to discover and record the rock art of the Tibesti mountains in Chad – a destination clearly not many people are able to visit. Two young people from Factum Arte came along to record the paintings and now, thanks to their work, images will be available for all to see.

Its founder, Adam Lowe, has said its initial aim was to ‘build bridges between specific new technologies and high levels of craftsmanship’. What this has turned out to mean in practice is the most extraordinary re-creations of masterpieces that have been lost or damaged – or, like the rock art, done in order to bring the art to a wider audience.

Their work is so widespread it’s hard to do justice to all it does – it ranges from working with artists to help them bring to life original works of art, to using 3D scanning techniques to record ancient monuments, to working with the Belgian company Flanders Tapestries to enable artists to work with a digital loom and create more affordable editions of their tapestries. They’ve re-created some of Van Gogh’s Sunflower paintings that were lost when the Americans bombed Ashiya in Japan in 1945 and helped Sky Arts develop a seven-part television series called Mystery of the Lost Paintings, which starts in May. The series focuses on seven great paintings by Vermeer, Monet, Van Gogh, Franz Marc, Klimt, Lempicka and Sutherland that were destroyed, stolen or lost during the 20th century. Here viewers can see exactly how Factum Arte works as its team re-create each painting.

The company has also used submillimetre 3D scanning techniques to produce precise copies of massive stone statues known as lamassu (protective spirits that date back nearly 3,000 years to the Assyrian empire), which should shortly be installed in the Iraqi city

of Mosul, where the originals were destroyed by militants.

Another monumental work is the precise reconstruction of the tomb of Tutankhamun which was placed inside a small museum in Luxor – the sarcophagus, the wall paintings and all the artefacts are all there, all part of a major initiative by the Supreme Council of Antiquities, to preserve the tombs in the Valley of the Kings.

Reproduction today by companies of this sort of quality, we see, is more than just a technical achievement – it is the window to lost works, to mysterious worlds of great beauty, and is a vital educational tool helping bring the stories of myriad cultures to a much wider audience.

This article first appeared in the July/August 2018 edition of Spear’s. Find a copy at WH Smith travel stores and select news agents, or subscribe here: https://www.spearswms.com/subscribe/

Web

factum-arte.com

facsimile-editions.com