Christo’s latest floating project has landed in the heart of London and made quite a splash, writes Anthony Haden-Guest

It was in 1962 that Charles Wilp, a Dusseldorf ad designer, film-maker and art world entrepreneur, brought Christo and Jeanne-Claude from Paris to my studio in the Pheasantry on the King’s Road. Christo was in London on a project, the wrapping of a naked woman, and Wilp, who knew that the fashion photographer Claude Virgin was my neighbour, had asked me to find a subject. As I did. Christo, half-Bulgar and half-Czech, and Jeanne-Claude, the high-energy daughter of a French general, duly arrived, as did Ruth Ebling, the model, and Vidal Sassoon, to do her hair. Wrapped Ruth sweated buckets during the shoot but remained game, and I got some pictures, which are part of the Christo/Jeanne-Claude archive.

This was the beginning of an enduring friendship. I visited the Christos in their cramped studio on the Île Saint-Louis, Paris, and the studio space they occupied illegally in Downtown Manhattan in the Sixties. I was with them in the Seventies as they punched through endless procedures to enable their 24½-mile Running Fence along the hilltops of Sonoma County in California. Jeanne-Claude died of an aneurysm in 2009 and the best art-world marriage I know of is over.

Christo has returned to London for a project at the Serpentine in Hyde Park. His most recent public work was The Floating Piers, which he installed on Lake Iseo in Italy in 2016, and which allowed visitors the pleasantly unearthly experience of walking on water – or, specifically, upon 220,000 bobbing, yellow-fabric-covered polyethylene cubes. It was a massive success, both critical and popular, and it happened to be up at the same time as a historical survey of aspects of his work at the Fondation Maeght at Saint-Paul-de-Vence in the South of France.

‘That was all the work made with barrels,’ Christo says. The show included work made as early as 1958, along with scale models and photographs of such early pieces as The Iron Curtain, which Christo and Jeanne-Claude put up in Rue Visconti, Paris, a totally illegal operation which the gendarmes on the spot allowed to proceed, thanks to the dramatic pleas of Jeanne-Claude.

In 2016 Christo was also approached by Hans Ulrich Obrist, the peripatetic director of the Serpentine Gallery. Obrist suggested that the gallery take the Maeght exhibition as it was. Fine. But then Christo came back at him with a suggestion of his own.

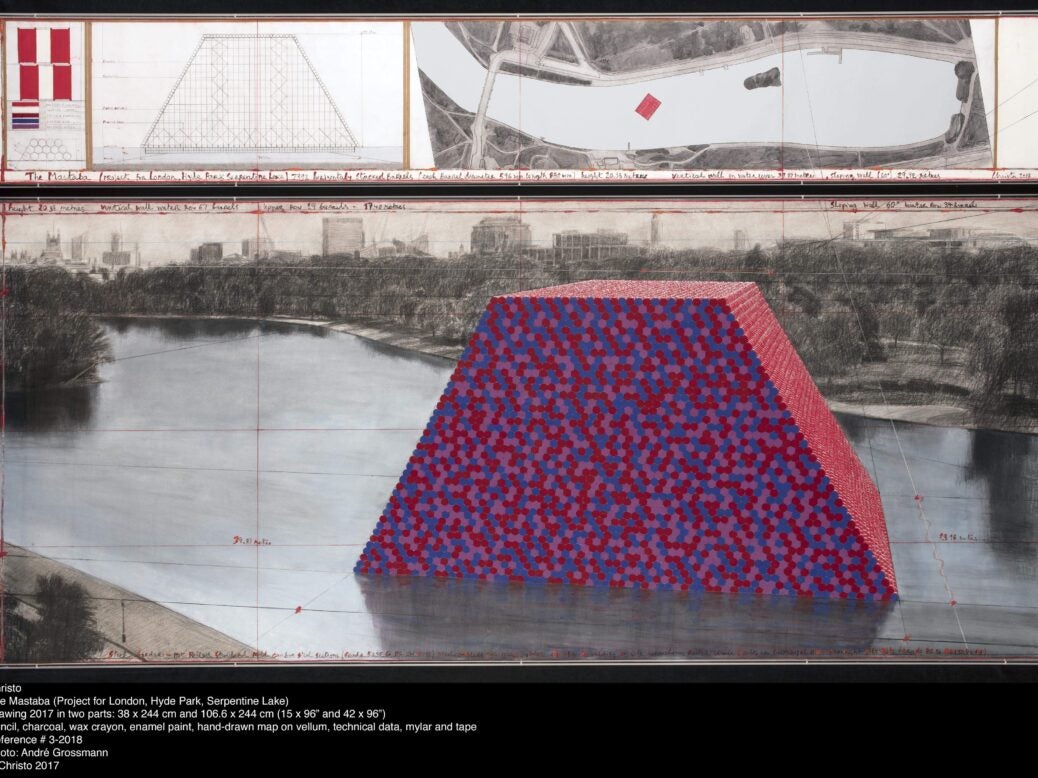

‘I tell him there’s also something I’d like to do,’ Christo told me. ‘I know the Serpentine, I know Hyde Park. And I know the Serpentine lake.’ And what Christo also knew is that the lake would be a perfect locale for one of his longest-running projects: The Mastaba.

Both projects, as most readers must be aware, happened. Barrels and the Mastaba 1958-2018 sits in the Serpentine Gallery, and The Mastaba is a presence on the Serpentine lake. It should be noted that Christo has himself come up with the £3 million for the lake project because there are certain basics about Christo’s projects, one being the remarkable economics.

Unusually for artists, who customarily work through dealers, Christo and Jeanne-Claude took control of their career as soon as they began taking their work into a public space, and in this respect they can be seen as forerunners to such über-artists as Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst and Takashi Murakami.

The Gates in Central Park, New York was backed by the city’s mayor, Michael Bloomberg and generated substantial tourist income for the city (and it should be noted that Bloomberg Philanthropies funded the show at the Serpentine Gallery). In the wake of The Gates, the Harvard Business School published a 22-page study, Christo and Jeanne-Claude: The Art of the Entrepreneur, noting that the total expenses of the artists for 2004 had approached $15 million. But Christo accepts no commissions, no grants, no subsidies. Everything comes from the sale of his art.

Christo has always come up with two sorts of idea for a large project; one anchored to a particular spot and the floating concept, the notion looking for an appropriate home – but both kinds can take for ever to happen, or never do. ‘Twenty-two projects complete. Thirty-seven failures!’ he told me before The Floating Piers.

Take one of his most resonant efforts, the wrapping of the Reichstag, home to the German parliament. Work on it began in 1971, Christo told me. ‘That project was refused in 1977. The second refusal was in 1981. The third refusal was in 1987.’ But Wrapped Reichstag was created in June 1995. And it was magnificent.

The Floating Piers, like Running Fence, had been a concept. With the concepts too, the failures are never final, and can sometimes work out very well indeed. ‘The Floating Piers was designed in 1970 for the Rio de la Plata in Argentina but we did not get permission,’ Christo says. ‘We tried to do it in other locations. We tried in Tokyo Bay in 1996-97, but we never get permission. But in the Sixties, in the Seventies, in the Nineties when we tried to do a Floating Piers, it was designed to be a pontoon. Fortunately we don’t do the project then, because meanwhile they invent an incredible system.’ Those bobbing, high-density, polyethylene cubes – that was why visitors to the Lake Iseo project felt they were walking on water.

So to The Mastaba on the Serpentine. A venerable architectonic form, a kind of beheaded pyramid, it has been a long-time Christo project. ‘It was going to be in Holland,’ he says. ‘We never got permission. Then in 1967 it was going to be in Texas, between Houston and Galveston. We never got permission.’ Now, though, he is working on the Abu Dhabi Mastaba, which will arguably be the largest sculpture in the world.

Christo has been thinking of doing a floating Mastaba for just about as long, though. ‘It’s an idea we had to do on Lake Michigan in 1967,’ he told me. The drawing will be in the show. ‘That was never built. But the one we are building is much bigger. It is the size of our building in SoHo.’ (Oh, yes. I should add that Christo still lives in the building he lived in illegally when he came to New York, and just about as austerely, except he likes to get his shirts from London and he has now bought the building.)

‘It is like a five-storey sculpture,’ he says of The Mastaba. ‘It weighs 750 tons and it will be moved by the wind.’

As usual, getting permission was not easy – there are swimmers in the Serpentine and wildlife of one sort and another – but that is always the story with a project and, as usual, those processes have been ingested by Christo, indeed treated as a necessary part of the art-making, which is why they tend to play a part in Christo documentaries. ‘To get permission to do that project was very difficult, very complicated, with Westminster and the Royal Parks,’ he says.

Once this was accomplished, the work began. ‘People have worked on the project in Zurich, Basel… we have Germans… Dutch fabricating the barrels, Bulgarians, Swiss… and then, of course, in the United Kingdom we have an entire workforce on the scaffolding. Building the project takes a long time, and removal of the project is also a very long time. We will stay ’til the middle of September, because we don’t like to disturb the tourists in Hyde Park during the summertime.’

Related

Meet Ati Sedgwick, the rising star of ‘alternative’ art

Why Tom Wolfe turned me into Peter Fallow

How Philip Pearlstein led a revival in realist art