The parfumier extraordinaire has always followed his nose in life — and the results are not to be sniffed at. Michael Watts meets him.

In September 2010, when the Victoria & Albert museum inaugurated a celebration of the Ballet Russes and its founder, Sergei Diaghilev, it included what proved to be a nice little earner for everyone. Before ballet performances, Diaghilev always had the stage curtains sprayed with his favourite perfume, Guerlain’s Mitsouko. The V&A asked master parfumier Roja Dove, who had worked at Guerlain, to devise a new scent for the exhibition in homage to the great impresario.

Dove called it Diaghilev and sold out the limited edition of 1,000 bottles. Then he made more for sale at his haute parfumerie in Harrods, now costing £750 a bottle. Finally, he was invited on a private tour of the Kremlin, where he sat in Vladimir Putin’s chair and saw the grey marble bath and rose silk walls of the tsarina’s bathroom. He was utterly transported.

Visitors to the Roja Dove Haute Parfumerie may feel the same. This enclave, on Harrods’ top floor, is itself a thing of opulence, with its black lacquer cabinets, polished Lalique and perfumes hand-picked by Dove, who is a historian of fragrance as well as being a famous ‘nose’. Here, in 2006, Dove unveiled the world’s most expensive scent, Imperial Majesty; it was enthroned on a glass pedestal and cost £115,000 a bottle. For that, you got 16.9 ounces of Clive Christian’s No. 1 perfume — ‘the perfume of my heart’, declared Christian, a Scot who originally designed kitchens — poured into Baccarat crystal bearing a five-carat white diamond in an eighteen-carat gold collar. Only ten bottles were made: seven were sold, and two were displayed at the haute perfumerie and in Bergdorf Goodman. The final bottle went on show around the world.

Dove, 60, is a modern-day arbiter elegantiae. His friend Lucia van der Post — the doyenne of journalism about the über-rich and of course a long-time Spear’s correspondent — calls him ‘the go-to man for anything you need to know on the scent front’. He lectures internationally, is a creative ambassador for the Great Britain Campaign, and has written a lavish guide called The Essence of Perfume. Makers of luxury products often consult him, among them the distiller Macallan, which sought his help in promoting its whisky abroad. His response was to invent ‘odour profiling’, a more universal language of smell, and to tell it that traditional whisky descriptions such as ‘peaty’ are meaningless in a hot, desert country. And he hated whisky, he added.

He grew up in Sussex, where ‘Roja’ was really ‘Roger’. His father barely spoke to him, he says, but his mother ‘shaped who I am as a man’, and he has an imperishable memory of her fragrance when she kissed him goodnight. A career in medical research was mooted, but even in his teens he was buying little bottles of scent with his pocket money. In 1981 he pestered Guerlain, a very old and proper parfumier, to hire him, and there he began instructing other employees, and then fashion journalists, in how to appreciate scent. He became their global ambassador, and was dubbed ‘Le Professeur de Parfum’. And he was very happy — until Guerlain was acquired, as were other ancient perfume houses, by the multinational LVMH in 1994. Then he found that he detested corporate life. ‘The whole industry became, in my opinion, debased,’ he reflects now. ‘Suddenly, scent was literally being spewed out. The exclusivity had gone. It was now about lifestyle and designer logos.’ He eventually quit in 2001 and, urged by influential friends, launched his own scent in 2007. Roja Parfums now sells 46 scents, promising ‘a perfect perfume for everyone’, in 130 outlets around the world.

Large conglomerates and their mass-marketing of ‘the juice’, as the trade calls scent, have undoubtedly boosted sales. ‘The Future is Gold’, promises LVMH’s multi-platform advertising for Dior’s J’adore, which shows a gold-sprayed Charlize Theron soaring upwards on a silken rope: a metaphor for the industry itself. In 2016, the global market in fine fragrance — ie perfumes, colognes, room sprays, candles and posh soaps — was worth $41.1 billion, the research company Statista estimated, and each year there are more than 500 new fragrance lines. Classic scents such as Chanel No. 5 (created in 1921) and Yves Saint Laurent’s Opium (1977) still command the loyalty of older, richer customers, but the high street is awash with ‘celebrity scents’ targeted at young buyers. These are generally the affordable products of a quick alliance between famous faces and established parfumiers such as Elizabeth Arden. Few linger long, although Jennifer Lopez’s Glow, made with Coty, has spearheaded perfume sales of £50 million, while Elizabeth Arden continues to make the lucrative perfume range started by Liz Taylor with White Diamonds in 1991.

Celebrity scents account for up to 40 per cent of all perfume sales, but industry observers believe that Western markets are now saturated, and the gold of the future will be mined in China, India, the Middle East and especially Brazil, the world’s leading consumer of fragrances per capita. In Britain, however, growth is being driven by niche, top-end fragrances, the kind made by Dove. The marketing group NPD reports that in 2015 such parfums represented 4 per cent of total value sales but 69 per cent of growth. In a high-volume market, wealthy customers crave uniqueness and will pay even the exceptional price of Christian’s Imperial Majesty, if allowed. Guerlain, updating an innovation it introduced in 1828, now offers clients bespoke perfumes costing around £30,000: its le parfum sur mesure allows individuals to create a personal fragrance identified only after months of consultation. Dove, too, has a bespoke service, costing £45,000.

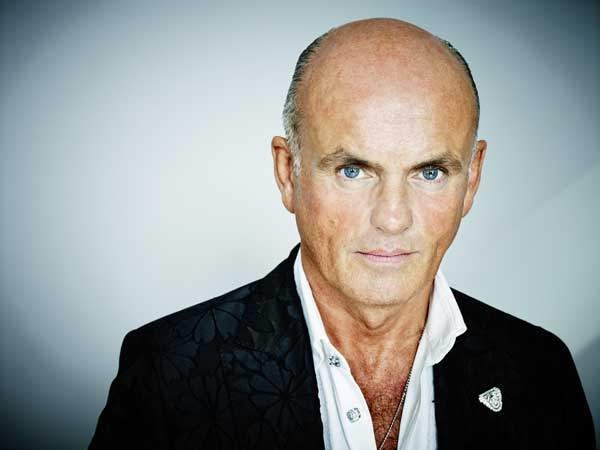

He has now opened a boutique in Burlington Arcade, off Piccadilly, solely for his own brand. It resembles a tiny, illuminated jewel-box, and has the sybaritic, wafting air of a boudoir, enough mirrored walls to delight a narcissist, and shelves holding bottles of glowing liquids with tongue-in-cheek names such as Danger, Fetish, Enslaved, Scandal and Unspoken. ‘Please don’t take me seriously,’ Dove says affably, ‘because I don’t.’ He’s tall and rather imperious, with very light-blue eyes, set in a gleaming, noble head, and old-fashioned manners that make me think of the veteran broadcaster Nicholas Parsons. Today, he’s wearing leopard-patterned slippers and a white embroidered shirt; bright jewellery winks from his throat and wrists.

He has an almost missionary zeal to explain the workings of the perfume industry, but mischief is only an arch of the eyebrow away. We are discussing perfumery’s traditional use of a substance obtained from the civet cat, commonly imported from North Africa in the horns of zebu cattle, which he says resembled a wax paste, like earwax, that comes from a small scenting gland between the anus and the genitals. ‘So you have to wonder,’ he chortles, ‘who first went, “Here, kitty, kitty!” and went around the backside of a cat and stuck something inside the gland to see what might be there. And then say, “I know! Let’s make some perfume out of it!’’’

The perfume industry thrives on absurdity and outlandish publicity; it’s hard-headed, but also light-hearted. The Diaghilev perfume, at the time of its launch, was described by one hyperventilating blogger as ‘dirty sexy’, redolent of ‘tousled hair, sweat, naked raw sensuality’. Dove’s voice, however, is civilised and amused. While acknowledging his considerable olfactory powers, he counters that they can be a curse as well. ‘I can smell things that are very unpleasant,’ he says, adding that he never travels on the Underground: ‘And I was on a long-haul flight once, and I remember saying to the purser, very discreetly and politely, “Can you kindly move the stewardess?” I wasn’t being precious. She had on an enormous volume of a very potent perfume.’ Pause, as eyebrows arch. ‘I didn’t see her any more.’

The science behind every perfume is remarkably complex. It involves a wide assortment of techniques, such as steam distillation, solvent extraction, enfleurage, gas chromatography, maceration and expression, as well as a grasp of chemical processes such as the evaporation curve, which tracks the volatility of liquid being sprayed. Around 3,000 potential constituents are available to the ‘nose’ alchemising a new scent. These include plant and animal ingredients, but also synthetics, either man-made (now increasingly the case) or ‘natural isolates’, which are single-odour molecules, isolated from raw materials in order to lift the character of a scent.

The raw materials can be outrageously expensive. It takes more than 300,000 petals of precious Rose de Mai to produce 1kg of high-grade rose oil; its annual production compares to less than one day spent picking and distilling damask roses in Bulgaria, a major commercial producer. Jasmine from Grasse costs upwards of £30,000/kg, and the market price for a kilo of ambergris, a substance secreted by sperm whales (not unlike a cat expelling a fur ball), is £100,000. This is why true fragrances are so costly. Dove spends three to six months making a new perfume, experimenting with blotters of scent on a revolving pinwheel. His home is in Brighton, but he works from a small Mayfair apartment. ‘You have to play around,’ he explains, ‘and leave the raw materials for a while to react to each other.’

Perfume-makers are highly regulated by a trade body, the International Fragrance Association, and by Brussels, but unlike food manufacturers they are not required to reveal their components, despite pressure from campaigners for safe cosmetics. The very suggestion irritates him: ‘Why should anybody give the secret of their formula? What we are obliged to do — on the bottom of the box — is to stipulate certain raw materials if we use them. The formula itself — no, I will never give it out. It’s the same as going to a very smart restaurant — I’ve never seen the recipe printed on the back of the menu. And who cares? I just want the chef to create something delicious.’

In any event, the formulae of more than 3,200 scents are now preserved and restored in the world’s largest scent library, the Osmothèque in Versailles. Scent will oxidise over time, so, ironically, it’s the beauty and rarity of the bottles that attract serious collectors of perfume; in 1991, for example, a bottle designed by Salvador Dalí for Schiaparelli’s Le Roy Soleil sold at a Paris auction for nearly $30,000. Roja Parfums are also archived at the Osmothèque, alongside the early creations of Houbigant, Roger et Gallet and other antiquities, and even the cologne that Napoleon used in exile on Saint Helena. It makes Roja Dove very proud to think that it all began with a mother’s kiss.