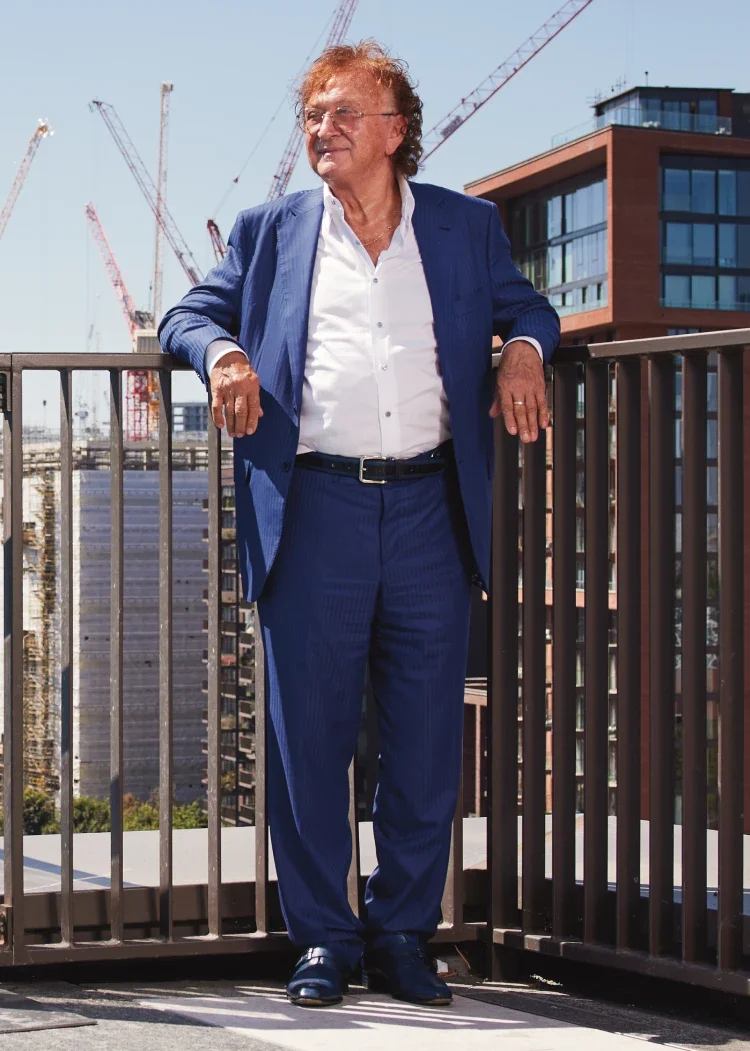

With marquee developments and tens of thousands of units already under his belt, Ballymore founder and CEO Sean Mulryan is changing the shape of London. By Rory Sachs

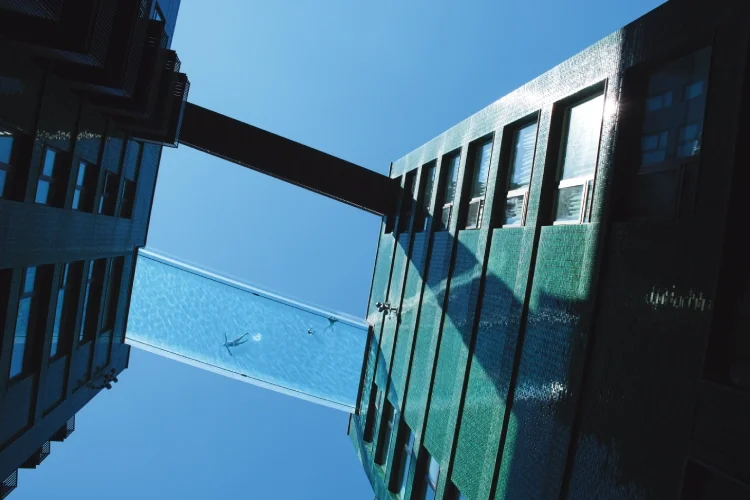

We are ten storeys high among the glass towers of Nine Elms in Battersea. As the mercury soars past 30°C on a summer’s day, residents of the development splash about in the pool, with only a 14-inch sheet of see-through acrylic suspending them and thousands of tonnes of water above the pavement, 35 metres below.

This is the world’s first ‘sky pool’ at Embassy Gardens, the brainchild of Irish-born London property kingpin Sean Mulryan. He’s the man behind this Instagram-friendly fishbowl, and the sale of an adjoining plot of land to the US government, where the latticed structure of the $1.2 billion US embassy now sits.

‘I walked into an aquarium in the Bahamas and there were millions of tonnes over my head – and sharks. So I [knew] it can be done,’ Mulryan, 68, says of the pool. Were the engineers nervous about the construction project? ‘Of course! “Madman! Thousands of tonnes of water?!” I said, “We’ve got to try it!”’

The sky pool is perhaps the most eye-catching element of Mulryan’s empire, but even the development that houses it – which includes around 1,500 residential units priced from £500,000 to £4.5 million – represents only a small slice. His privately held property developer Ballymore, founded 40 years ago, is a juggernaut in the London market, having produced nearly 20,000 homes in the capital.

Plus, Mulryan explains as he reels off figures in his expressive Irish lilt, there are 13,000 more central London dwellings in the pipeline. Mulryan lists a number of regeneration projects with high-profile partners, including a 50:50 venture with the London Legacy Development Corporation to build 1,200 homes in Stratford, as well as a project with Transport for London to design a new town centre for Edgware, and another with Diageo, with which he will re-imagine a €1 billion ‘Guinness Quarter’ around its factory in Dublin.

‘I walked into an aquarium in the Bahamas and there were millions of tonnes over my head – and sharks’

These days, Mulryan thinks of these projects in ‘phases’ of residential and commercial ‘units’ that number in the thousands. But in 1982 he started with a single home in Ballymore Eustace in County Kildare. With six siblings, he had a humble upbringing. At 16 he joined ‘a college to train to be a bricklayer’ but ‘absolutely hated what I was doing’. So he scraped together £4,500 to start building his own project. ‘I borrowed £4,200 and I had £300 to put down myself,’ he says. ‘It took six years to build, it was the slowest house ever built in the world! So Ballymore really started 46 years ago.’

Along with his wife Bernardine, whom he met aged 18, Mulryan sold his own house and car to generate enough capital to get this first project completed. Over seven years the house increased in value from £6,500 to £21,000 – ‘massive inflation’, he notes. ‘I was the draughtsman, the salesman, the lawyer and the builder,’ he adds.

In the early days of the business, when operations were still confined to Ireland, Mulryan would build homes on other people’s land for a fixed price. By the time he had ratcheted up production to 100 a year, he was able to purchase plots of land himself. ‘And then from there, the journey was to start building developments.’

Entering the UK market in 1987, his ambition soared. After early developments in Streatham and Camberwell, he purchased Old Spitalfields Market in 1999 for just £8 million. The past 20 years have seen the firm pepper Canary Wharf and surrounding areas with projects. It has also undertaken regeneration work in other European cities, including Bratislava and Prague.

Following London’s 1990s property crash, he purchased large swathes of land in pre-Olympics East London, often by the Thames, at one point making him the city’s largest private landowner. ‘I was the biggest. Going back to 2010, we had the equivalent of, I think, 25,000 lots in central London.’

This included more than 60 acres of the Royal Docks, to the south of London City Airport. Two-thirds of this land have been developed with more than 4,000 homes. Mulryan has coaxed the Uber Boat service to his new community by building a futuristic-looking pier.

Necessity has been the mother of invention. ‘I didn’t have the money to go where I would like to go – West End, Mayfair, all these places where all the rich guys went – so I had to go where most people wouldn’t go. And so that’s how I built the land bank.’ When he bought the land by the Royal Docks, it was ‘a no-go area’, he says. ‘Nobody was interested in land there. I had no competition at all… There was nothing there. But I had to make them work and create environments.’

Six years ago Mulryan opened ‘London City Island’ on the Leamouth Peninsula, on the opposite side of the Thames to the O2 Arena. His company re-engineered the area – both structurally and culturally. ‘I used to call it “no man’s land”,’ he says. His ambition was to turn the area into a ‘little Manhattan’ with a collection of towers, some of which are rendered in Lego-like primary colours. A bridge connecting the development to Canning Town station has really ‘opened it up’.

In 2019 London mayor Sadiq Khan opened a 93,000 square foot studio facility – the Mulryan Centre for Dance – which serves the English National Ballet. Meanwhile, many of the commercial units below the residential flats have been given over to budding artists, who have ‘paid no rent’, Mulryan says. ‘We subsidise all that to get the energy into City Island – the energy of the arts and the culture. You have to subsidise those people.’

‘The margins are dropping. You’re going to have less and less development in London now’

While Mulryan says ‘creating places’ is the best part of his job, ‘the worst thing is probably dealing with the financial strains of the scale’, he says. ‘It could be very serious if you start making bad decisions on a scale of development that we do.’

The residential market has become harder to operate in, says Mulryan. In recent years, prices in London ‘have not gone up at all’. Meanwhile, ‘costs are going up dramatically. So it means the margins are dropping. You’re going to have less and less development in London now.’

Providing the amenities alongside his homes has been a double-edged sword. Mulryan notes that 20 years ago his firm was among the first developers in Europe to put in ‘the swimming pools, the cinemas, the sky lounges, the spas, and everything’. This was popular with foreign buyers, particularly from East Asia.

However, he acknowledges that services charges are ‘a huge issue’ for some. It’s been a contentious issue in recent years, with his firm subjected to close press scrutiny over rising management costs. But, he says, ‘If Embassy Gardens were in New York, service charges would be four times higher. For what you get here, our service charges are extraordinarily competitive.’

A solution may be to charge only the residents who want to use the facilities. ‘We will try to do it in a way that the people who want to use are going to pay for it and the people who don’t want to use it won’t [have] the service charge. For a future project, we’re working on a model that we’re stress-testing internally, of how we deal with that issue. It’s not a very easy one to solve,’ he says. ‘It hasn’t been achieved anywhere in the world yet.’

Fire safety has been a prominent issue across the sector too. Ballymore’s New Providence Wharf development suffered a fire last year, which spread to units on three floors and led to the hospitalisation of two people. A report by the London Fire Brigade cited ‘serious fire safety issues’. While the building’s cladding was found not to have contributed to the fire and Ballymore’s projects were signed off by building control at the time, the company announced in the days following the incident that it had committed £20 million to fix fire safety issues across its housing developments. It is also on a list of around 50 property developers that have made a legally binding pledge to undertake ‘life-critical fire safety works’.

After a period of growth, Mulryan is eager to find the optimum level of output for his 800-person firm. The rate now sits at around 1,000 units per year in London. ‘I don’t want to get bigger,’ he says. He has contemplated taking the company public from time to time, especially as he reckons finding finance is now easier for public companies. ‘Are we going to do it? It’s always on the agenda now and again, but at the moment it’s not planned.’

Three of his five children work with him in the business – Linda, Robert, and John, the last of whom serves as managing director. But their father strives to maintain a separation between church and state. ‘I don’t treat them as sons or daughters – business is business,’ he says. Mulryan says he is conflict-averse, and any disagreements ‘hit me very hard’.

How much is Mulryan worth? He doesn’t put an exact figure on it, but he still owns 100 per cent of Ballymore. As a privately held company its finances are opaque, although the Irish Independent reported in 2020 that the firm’s active projects had a projected gross development value of £4.7 billion.

He supports a wealth tax. ‘I pay my taxes in Ireland. I have no problem paying tax because you can’t bring it with you, and you might as well pay your bloody tax and not worry about it,’ he says. ‘I’m very upset with how some people are badly paid… number one on my agenda is nurses. It’s disrespectful… they should be getting double what they’re getting.’

‘I have no problem paying tax because you can’t bring it with you. You might as well pay your bloody tax and not worry about it’

Mulryan laments the cost of property for ordinary people. ‘It is the biggest thing in my life, why a normal guy can’t own a house… the costs of the houses are way too high, and a nurse can’t afford a house. You just can’t afford to raise your family. I mean, it’s outrageous. Two people on £50,000… on a decent salary, they still can’t afford a house.’ Simplifying regulation, he says, would be one way to make homes more affordable. ‘Every city needs affordable housing [for] key workers.’

Philanthropy, meanwhile, is a ‘serious responsibility’ for his family. ‘[The Irish] don’t talk about what they do,’ but he does ‘a lot’, particularly around education and the arts. ‘It gives me massive satisfaction’.

He has several famous friends, including Bono and Seb Coe. Without Coe, Mulryan says, the Olympics wouldn’t have happened in London. ‘I think it changed the perception of London… I was on the committee, I saw what he did, what he got us to do, what he got other people to do. He was the wheeler dealer of the world. Oh, he’s brilliant!’ If Bono were with us, Mulryan says he’d be questioning the ‘drive for more profit, more return, at the cost of more important things’.

At some point, he will decide with his children what happens to the company. ‘They will decide the future with me: do they want to continue it, or sell it? I will not decide their future.’ Right now ‘it’s way too early for that. I’m too young. I’m very fit, I work out five times a week and I power walk… If I have my health, I’ll be definitely leading for another ten years.’

Mulryan is driven. Over the next ten years, he will work on 20 acres of the development at the Royal Docks, 1,700 homes at Canary Wharf’s One Mill Harbour, 4,000 apartments and ‘a huge amount’ of commercial real estate in Edgware, as well as his redevelopment in Stratford and the project with Diageo in Dublin. ‘I’m not stepping down, under any circumstances,’ he says. ‘And the only thing that would change that is if I die.’ At this point, he bursts into laughter.

Original photography by Greg Funnell

More from Spear’s

Chasing crypto and crunching data: inside the rise of private investigations