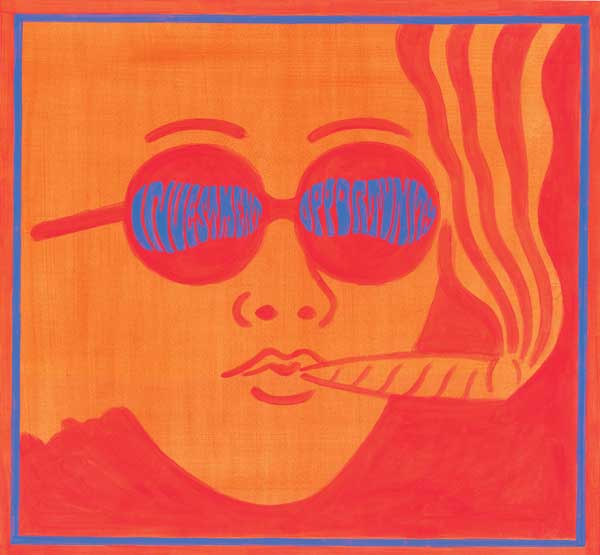

The legalisation of recreational cannabis in much of North America and its medicinal use elsewhere has opened up a huge market for enterprising companies exploring new possibilities, writes Edwin Smith

As the clock ticked towards midnight on 16 October 2018, people in Newfoundland’s small capital city, St John’s, were getting excited. Having queued on the street outside, some of them, along with the world’s press, managed to cram into a cannabis store in the centre of town to witness history being made.

With seconds to go, the crowd began a countdown: ‘Three, two, one…’ Then the whoops, whistles, cheers and high-fives began – as Canada’s first legal sale of recreational cannabis for almost 100 years went through the store’s electronic till. When Canada became the first major economy to legalise the recreational use of cannabis (Uruguay did it in 2013), it was a moment of celebration for many.

But, according to the person manning the till that night, ‘Canada is not having a party.’ Instead, says Bruce Linton, the CEO of the world’s biggest cannabis company, Canopy Growth, things are starting to get serious.

There is evidence of cannabis having been grown in Roman Britain; Henry VIII introduced a law that obliged landowners to farm hemp, and Queen Victoria is thought to have been prescribed cannabis by her doctor to relieve menstrual pain. But, having been used throughout much of human history, cannabis started falling out of favour in the middle of the 20th century.

Notably, in the wake of prohibition, use of marijuana was criminalised in America. In 1961, 186 states signed an international treaty, the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, which made cannabis illegal nearly everywhere. But, in recent times, that direction of travel has been reversed. In addition to the law change in Canada (for which its citizens have the tattooed former snowboard instructor Justin Trudeau to thank), recreational use is now legal in ten US states; medical use in 33. In Germany, medical marijuana became available on prescription in 2017.

Poland followed suit a few months later, and in November 2018 it became possible for doctors in the UK to prescribe it on the NHS after a landmark campaign on behalf of the 12-year-old epilepsy sufferer Billy Caldwell. Along with legislation, attitudes are beginning to shift. The majority of the British public backs a softer stance on cannabis, according to YouGov, and those who favour outright legalisation now outnumber those who would prefer the drug to remain illegal.

A recent report from RBC Capital Markets even suggested that cannabidiol (CBD), a non-psychoactive cannabis compound thought to promote relaxation, could one day become ‘more popular than caffeine… as consumers continue to feel the stress/anxiety of technology related stimuli’.

Rolling market

In some respects, the future is already here. The network of dispensaries sprouting up across North America offers a snapshot of a world in which cannabis is bought not from dodgy geezers in pubs and parks, but in glossy cathedrals to consumerism. Retail outlets operated by the US firm MadMen could easily be confused for your local Apple Store.

It has been suggested that the market for recreational marijuana could one day resemble that of fine wine, with connoisseurship and prices for rare varieties to match. More money is already spent on weed than wine in the US and Canada, if you take into account both legal and illegal purchases.

Despite recent developments, 87 per cent of the $53.3 billion North American market is still thought to be accounted for by illegal trade, according to Arcview Market Research.

However, in the US states that have legalised recreational use, the so-called ‘greenrush’ is generating greenbacks for government coffers. California brought in $74.2 million in cannabis-related tax receipts the second quarter of 2018 alone, and the figure – up 22 per cent from just the previous three months – is growing like a weed. In Colorado they’ve raised nearly $1 billion in tax since 2014.

Crispin Blunt, the Conservative MP who chairs the allparty parliamentary group on drug policy reform, believes we should do the same in the UK. ‘One of the benefits of taking an illegally supplied product and making it legal is obviously the opportunity to tax it,’ he says.

Blunt, who also believes there is a strong public health argument for the ability to regulate the sale of potent strains of skunk, in particular, adds that there may be ‘enough evidence from Canada to make the basis of an assessment’ that could result in a change in legislation during the next Parliament (scheduled, at the time of writing, to run from 2022 to 2027).

There are 192 million cannabis users around the world, according to the UN’s World Drug Report. Other elected representatives may soon start making similar noises too. But to think of this new era as a mere legitimisation – and monetisation – of a once shady practice is to miss the point.

Websummit is the largest technology conference in the world. Last autumn it brought senior executives from companies such as Google and Amazon together with European commissioner for competition Margrethe Vestager, the co-founder of dating app Tinder, former F1 world champion Nico Rosberg, Tony Blair, and 70,000 other delegates in Lisbon.

There were talks about robotics, cryptocurrency, Manchester United’s social media strategy, and much else. One of the best-attended talks – where self-respecting professionals were prepared to sit on the floor, lining the aisles of the lecture hall – was given by the CEO of Canadian cannabis company Tilray.

Brendan Kennedy, a former venture capital investor in a pinstripe suit, explained that, right now, the most promising path for the industry lies in pharmacology. It is currently legal to use cannabis for medical purposes in 30 or so countries, and Tilray, in which the controversial tech investor Peter Thiel’s Privateer Holdings fund has a roughly 80 per cent stake, expects the figure to double within a few years. By contrast, Uruguay and Canada are the only notable economies in which recreational use is legal on a national or federal level.

Compound interest

The cannabis plant is an untapped ‘pharmacopia’, says George McBride of ‘global cannabis consultancy’ Hanway Associates. Until recently, a bad reputation and limitations on its use in medicine had stymied research. But, says, McBride, there are more than 200 pharmacologically active compounds in the plant. That’s a double-edged sword: it makes isolating and testing particular compounds complicated. But the problem isn’t an intractable one.

‘Soon we’ll start to see novel compounds and drugs we haven’t seen before,’ says McBride. ‘That’ll be interesting.’ Getting products to market is another matter, but McBride points out that the United Patients Alliance estimates that there are as many as a million people already using cannabis for medical reasons in the UK alone – legally or otherwise.

‘That’s the important thing to remember: when other drugs go through pharma approval processes, there’s not normally not a huge body of [pre-existing] evidence. It’s difficult to get doctors and politicians to realise why it’s different to other medicines, but that’s the key issue: we already have a good understanding of its safety.’

One of the companies hoping to break new ground in medical research is Oxford Cannabinoid Technologies (OCT). The company was founded by Neil Mahapatra, a biological sciences graduate who until recently spent most of his working life running a Mayfair investment fund.

Five years ago, Mahapatra’s research into possible treatments for his mother’s lung cancer introduced him to people who reported reduction and sometimes even complete disappearance of cancerous tumours following treatment with cannabis oil.

At the moment, Mahapatra says, evidence to support the use of cannabis in cancer treatment ‘remains very anecdotal’, but he saw enough to convince him that ‘rigorous, scientific research’ could hold ‘great promise’.

Working with academics at Oxford, OCT has established a research programme that Mahapatra hopes will eventually yield intellectual property that can be converted into ‘FDA-approved drugs across a range of illnesses’. ‘We’re looking at pain, neurological disease, inflammation, and by far and away the biggest focus is cancer.

Not just palliative, but curative properties.’ The endeavour will be aided by a $10 million investment from the rapper Snoop Dogg, or rather his cannabis-centric venture capital firm, Casa Verde. While Mahapatra describes it as a ‘very professionally run fund,’ he admits: ‘I’ve never met Snoop.’ The money being invested by OCT pales in comparison with the sums dealt with at Canopy Growth, however.

The Canadian company, which has the stock market ticker ‘WEED’, is the largest cannabis business in the world, with a market capitalisation of $20 billion. CEO Bruce Linton (the store clerk from that historic night in Newfoundland) reckons the potential applications of cannabis-related products are so vast and varied that the ‘addressable market’ is already in the region of $500 billion. (By comparison, the global alcohol industry is worth about $1.4 trillion.) Linton’s counterpart at Tilray, Brendan Kennedy, is a little more circumspect, putting the value of the cannabis industry at $200 billion – in the long term.

Today, the worldwide legal market is worth a more modest $12 billion and overwhelmingly concentrated in the US. But it is projected, in a report from Arcview Market Research, to bloom to $32 billion by 2022.

Linton reels off a list of sectors and products that cannabis can disrupt, including pain medication, cancer treatment, ‘dog care, cat care and large mammal care’, and sports recovery. CBD was removed from the World Anti-Doping Agency’s list of prohibited substances in 2018, he points out.

NFL linebacker Derrick Morgan and UFC fighter Nate Diaz are among the professional athletes to have endorsed CBD products. Linton continues, mentioning soft drinks, alcoholic beverages and the tobacco industry, which, he says, ‘we can disrupt the hell out of ’. Indeed, Coca-Cola released a statement last year in which the company said it was ‘closely watching the growth of non-psychoactive cannabidiol as an ingredient in functional wellness beverages around the world’.

The owner of the brewer Corona, Constellation Brands, has invested $4 billion in Canopy, while the Canadian brewer Molson Coors has announced plans to release cannabis-laced drinks later this year. Linton has even suggested that marijuana smoked salmon could appear on the dinner tables of hipster gourmands.

No guarantees

There are, of course, potential stumbling blocks for the cannabis economy. There is no guarantee that the law changes enacted by some governments will be replicated by others. And, in many cases, there is not sufficient evidence for the scientific community to agree that cannabis confers the benefits that are widely perceived and accepted by those who advocate for its use.

As things stand, we cannot be said to truly understand the long-term societal and public health implications of liberalising access to the drug, particularly varieties that contain significant quantities of the psychoactive substance tetrahydrocannabinol (THC).

A report by America’s National Academy of Medicine in 2017 stated: ‘Cannabis use is likely to increase the risk of developing schizophrenia and other psychoses; the higher the use, the greater the risk.’

In his book Tell Your Children: The Truth About Marijuana, Mental Illness, and Violence, Alex Berenson notes that rates of aggravated assault in Washington state rose by 17 per cent – twice the national average – between 2013 and 2017. In 2014 it had become the first jurisdiction in the US to legalise recreational marijuana use.

These caveats do not appear to unduly concern Linton, however. He says Canopy is on course to grow 500,000kg of ‘raw product’ this year – the weight of 40 double-decker London buses – and has his sights set on ramping up production further.

The company has filed 140 patents and scheduled 15 medical trials; it has a presence in 12 countries. Linton says he has more than C$5 billion (£2.85 billion) in his company bank account and looks at an average of two medical companies a week, with an eye to making acquisitions that could ‘help build out my capabilities’.

The interest in the company (its stock price doubled inside three weeks last summer) is not just froth, argues Linton. He has been working to establish Canopy since 2012, before recreational legalisation was even a twinkle in Justin Trudeau’s eye.

‘Back then I said, “It’s ridiculous that global public policy has been so rigid and thoughtless. When it opens up, it’s going to go crazy.”’

This is the cover story from issue 67 of Spear’s magazine, available on newstands now. Click here to subscribe

Related…

Interview: Lloyd Dorfman on UHNWs: ‘You don’t see a huge number giving’

Interview: Guy Hands, reign of Terra

Interview: Yanis Varoufakis on the end of Europe — and capitalism