Tim Barber explains why Hermès and Cartier, two French brands with contrasting watchmaking histories, are enjoying periods of rich creativity

For all that Hermès – supplier of handbags and leather goods to the super-rich and silk ties to bankers (back when ties were a thing ) – is a colossus of the luxury world, in watches it has remained something of a challenger brand.

But the challenge is gathering serious pace. Last year, according to Morgan Stanley, Hermès entered the Swiss watch industry’s top 20 ranking of brands by sales, leapfrogging established players such as Piaget, Blancpain and Bulgari – and the only way is up.

According to first-half financials for this year, its watch sales have risen a whopping 55 per cent on 2021, becoming by far the company’s fastest-growing category.

And well it should be. Not only are the Parisian company’s watches suffused with the kind of offbeat, distinctly non-Swiss esprit that characterises its other products, they also compete on a level footing with established names in terms of technical finesse and execution.

That’s the result of heavy investments Hermès made in its Switzerland-based watch operations a decade ago and more, bringing the making of movements, dials and cases largely in-house.

It has gradually built up its competency, capacity and quality since then, while going through a creative blossoming. A couple of recent models sum up the particular Hermès charm when it comes to watches.

H08: ‘A true sports watch’

The H08 is the brand’s entry into the modish genre of sports-luxe watches, a category so overrun with derivative offerings that originality is rare.

Hermès, however, pulls it off with a design based around an unusual case-shape, like a softened, almost cornerless square, which is replicated in the groovy, esoteric typeface of the numerals.

It has the full-fat impact of a true sports watch, the attention to surface and form of a considered luxury piece, and an air of unconventionality that is Hermès through and through.

The mesmerising process behind the Hermès HO8:

I fell for the H08 when it was launched last year in steel, but it was this year’s version in blued titanium that made me lustful when I tried it on.

It’s light as anything on the wrist – the feel is more that of a smartwatch – while the blue metallic sheen only increases its jaunty, ready-for-anything allure. Yours for £6,300.

Arceau Le Temps Voyageur: stylish time-travelling

Or for an example of the way Hermès can combine whimsical ideas with seriously inventive watchmaking, there’s the Arceau Le Temps Voyageur, an inspired remix of the GMT travel watch complication (displaying time in both your local time zone when travelling, and back home).

Here, local time is displayed on a floating disc that, as you cross time zones, gets shunted around the dial at the push of a button, aligning with time zones identified by 24 cities inscribed on an outer ring – as the disc makes its orbit, time magically adjusts to each zone.

Meanwhile, you can keep track of the hour back home via a window display at 12 o’clock.

As inventive a piece of watchmaking as this is, Hermès – as is its wont – keeps things rooted in its own exotic universe.

It features an engraved map across the dial, above which the time disc passes.

But it isn’t a map you’ll recognise unless you own Hermès’ Planisphere d’un Monde Equestre scarf, first produced in the 1970s, which imagined an equestrian world with continents named things like ‘Dressage’ and ‘Ethologie Equine’.

Unstoppable rise of watchmaking powerhouse Cartier

If Hermès is an insurgent creative force within watches, then Cartier, its fellow Parisian grande maison de luxe, is an established superpower, and one that has been scaling new heights lately.

According to the same Morgan Stanley figures, last year Cartier squeezed out Omega to become the second-placed watch brand by sales, after Rolex.

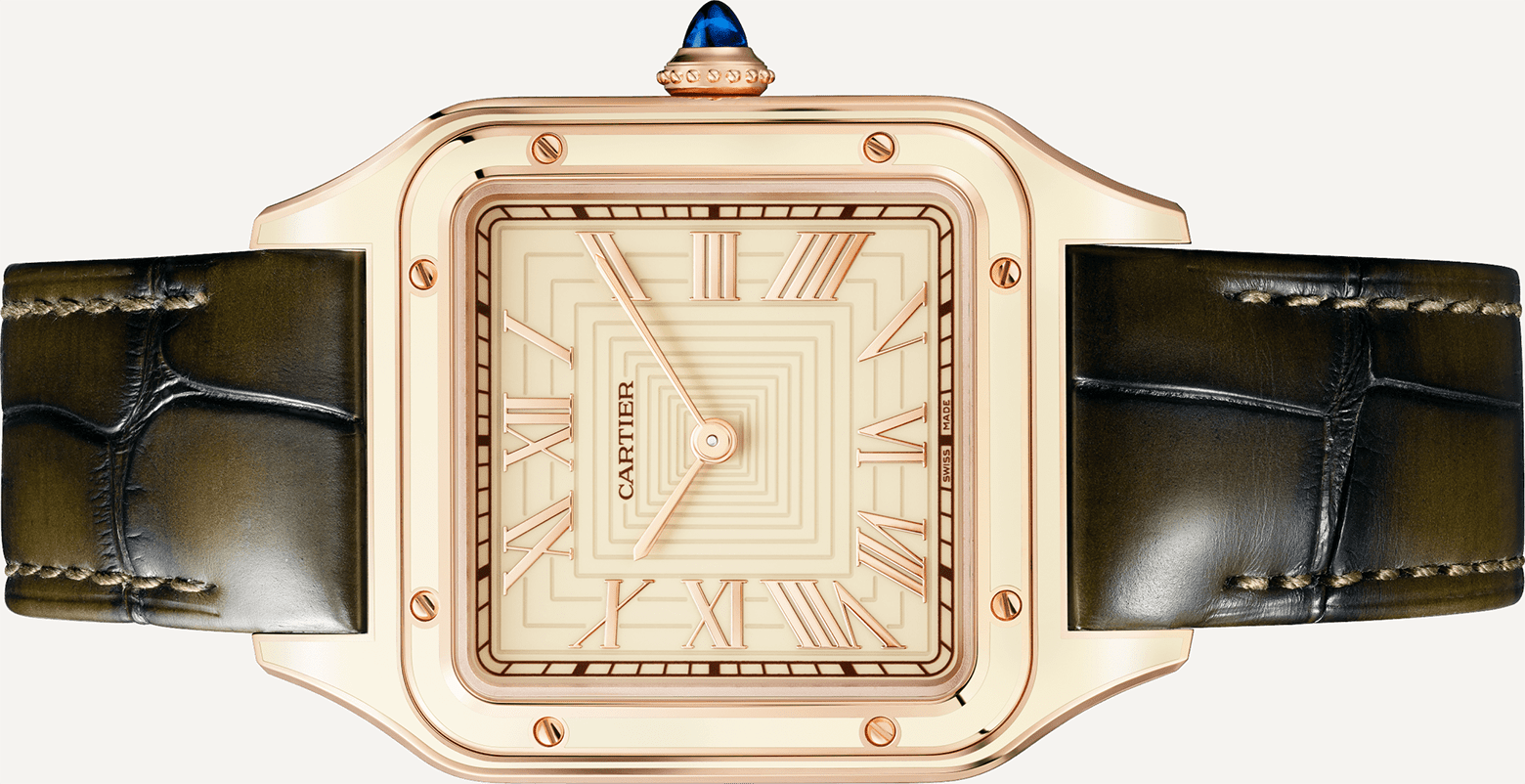

In particular, that’s down to the current success and fashionability of its own square-form sports-luxe wonder, the Santos.

One of the famous designs that invigorated the steel bracelet watch genre in the 1970s, the Santos fell out of favour in the mid-2000s, a period when Cartier seemed at a loss as to how to marry its long history of shapely, elegant wristwatches with a strategy of becoming a technical powerhouse in watchmaking too.‘The modern Santos-Dumont feels like just the sort of thing to wear for a spot of Raj-era tiger hunting’

It righted the ship by putting the emphasis back on aesthetics, form and glamour, while betting the house on the Santos (and its smaller, female-facing equivalent, the Panthère) as the watch to hook in the aspirations of Gen Z – a project that’s proved wildly successful.

Nevertheless, I personally still struggle to be excited by the Santos, which I find a some- what cumbersome bracelet design, unlike its slimline, dress-watch equivalent, the Santos-Dumont.

Both styles descend from what is claimed to be the original purpose-built wristwatch, made by Louis Cartier in 1904 for the early aviator Alberto Santos-Dumont, and iterated into a commercially available model the subsequent decade.

The modern Santos-Dumont cleaves most closely to that Belle Époque blueprint, and can be found in either hand-wound or battery-powered formats, in steel, gold and two-tone.

But here again, a recent new and unexpected version stunned me: it’s a Santos-Dumont with a rose gold case partly coated in cream lacquer, which is replicated in a bamboo-like pattern on the dial.

It feels like just the sort of thing to wear for a spot of Raj-era tiger hunting; its mix of historic elegance and exotic decadence is potent.

A watch house at the height of its creativity

Meanwhile, keep your eye on the wild child of the Cartier watches oeuvre, the Crash.

Invented by Cartier London in the 1960s (around the apocryphal notion of an oval Cartier watch, a Baignoire, that got melted in the wreckage of a car crash), its crumpled, absurdist case makes it one of the strangest wristwatch creations, even for a house as eternally inventive as Cartier.

But original vintage versions (of which there are very, very few) have recently risen to become auction unicorns: a year ago Sotheby’s sold a Crash for $885,000; in May this year, the auction website Loupe This set the record at $1.5 million.

Modern versions of the Crash have tended to use it as a platform for some inelegant (in my opinion) skeletonisation work, but a breathtaking decorative version this year saw Cartier finally taking advantage of its sculptural form.

The Crash Tigrée, with stripes of mottled green and blue enamel, and gold emblazoned with diamonds, is the work of a jewellery and watch house at the height of its artistic powers.

More from Spear’s:

The best private schools in the UK by results

The five most expensive watches ever sold

The collectors behind the surge in the rare and luxury watch market