In the summer and autumn of 1983, two groups of City practitioners were embarking on paths of change that would make London a global powerhouse of capital market activity for the next generation, with New York as its only serious competitor.

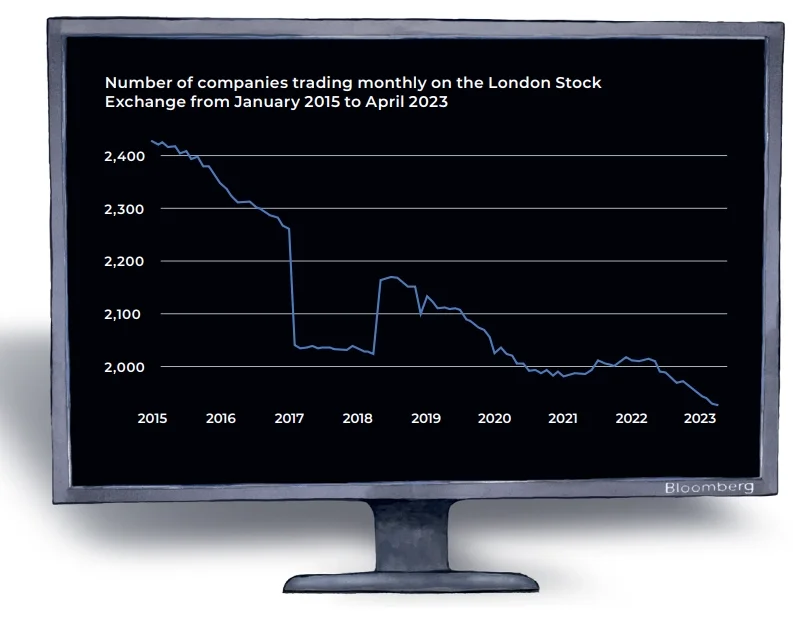

Forty years later, all is changed. Clamour is rising for reforms to reverse a perceived decline in the City’s prized global status. In particular, the London Stock Exchange (LSE) stands accused of losing ground as a platform for initial public offerings (IPOs) and listings. In 2022, 45 issuers listed, raising £1.6 billion – down from a spike of 119 (£16.8 billion) in 2021.

In the five years before that, London accounted for just 5 per cent of the global IPO market.

An IPO slump is more than a crisis for fee-earners within the Square Mile itself. It threatens knock-on effects for a UK economy that’s already suffering a drought of business investment, an exodus of entrepreneurs and the unquantifiable impacts of Brexit.

Regulation, risk-tolerance and the way companies are valued on either side of the Atlantic are all under scrutiny by professionals and politicians looking for ways to stop the slide and rebuild the City’s status.

So, we might ask, what happened back in 1983 to inject such pizzazz into the London market? And what’s needed now to make that happen again?

Back then, the headline reforms were Stock Exchange rule changes that would abolish fixed commissions and ‘single capacity’ – the demarcation between brokers and jobbers – and allow banks to buy member firms.

Agreed in July 1983 between trade secretary Cecil Parkinson and exchange chairman Nicholas Goodison, this Thatcherite assault – later labelled ‘Big Bang’ – on the exchange’s long-standing ‘closed shop’ arrangements would transform the scale and sophistication of London’s securities markets.

Among first movers in late 1983 were the US giant Citibank buying the broker Vickers da Costa and the merchant bank SG Warburg picking up the jobber Akroyd & Smithers, soon to be followed by Barclays forming BZW.

A less noticed set of discussions at the same time would give birth to the FTSE 100 index as a rival to the existing FT 30 and All-Share indices.

Promoted by the London Stock Exchange and first tested in August 1983 in the offices of the stockbroker Greenwells, the new index was a minute-to-minute aggregation of price movements for the top 100 London stocks by market capitalisation, which accounted for 70 per cent of all daily trades on the exchange.

Part of its objective was to provide data for futures contracts on Liffe (the London International Financial Futures Exchange, opened in 1982) and stock options offered on the Stock Exchange itself.

Thus, the new index was also a foundation of London’s rise in global derivatives trading.

FTSE at 40: Distinctly ‘old economy’

Once the exchange and the Financial Times had settled an argument over the acronym ‘FTSE’ – ‘Footsie’ in common

parlance – the new index, launched at the start of 1984, was soon ‘the dominant measure of market sentiment and indeed a household name’, to quote City historian David Kynaston.

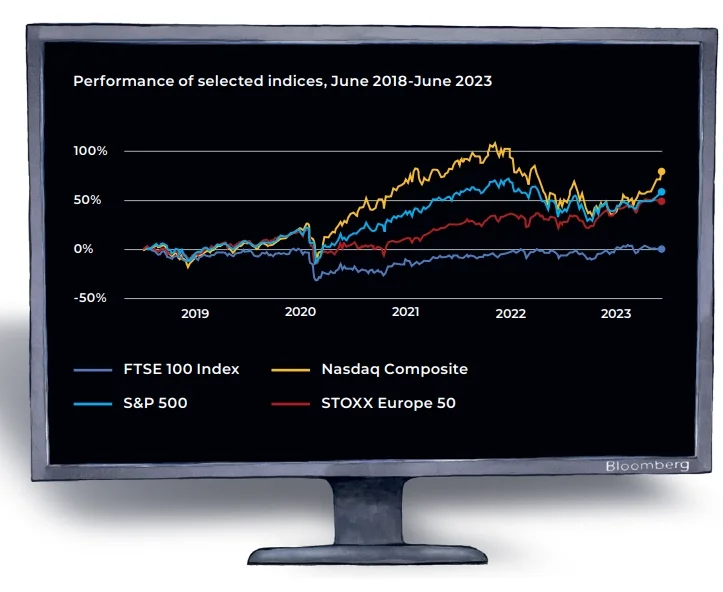

More than that, it was the clearest daily indicator, alongside New York’s S&P 500, that London was one of the twin centres of the financial world.

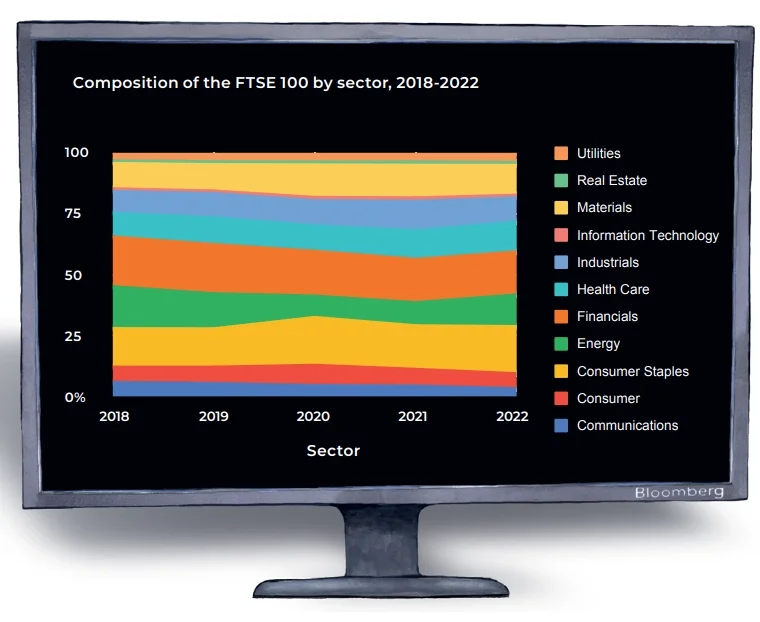

And now? The constituents of the 100 have changed many times, as was only to be expected of a dynamic index encompassing many multinational businesses. Great British industrial icons such as ICI and GEC are long gone.

But the list is still distinctly ‘old economy’, dominated by oil, gas, mining, banks, insurers and bricks-and-mortar retailers rather than the new breed of tech giants that lead today’s US indices.

Hence, in broad terms, a significant difference in average price-earnings ratios (around 14 for the UK, above 20 in the US) and corresponding valuations.

Let’s not be too negative, however. The ‘twin centres’ boast probably still applies.

Paris marginally surpassed London in total market capitalisation in November 2022 but is no match for the City’s dealmaking strengths. New York’s tech-centred Nasdaq exchange offered high valuations during the recent tech stock boom, but that’s now largely over.

Charlie Walker, head of equity and fixed income primary markets at the London Stock Exchange, says: ‘The negative perception of the LSE’s IPO record isn’t borne out by the data.

IPO markets have been quiet everywhere, including the US and Europe, for the past 18 months.’

As boardroom veteran Rupert Soames (CEO of FTSE 250-listed Serco and chairman designate of FTSE 100-listed Smith & Nephew) puts it, London ‘still has huge advantages, including time-zone, deep expertise, an international outlook and large pools of capital’.

Yet headline after headline gives a sense of City self-confidence slipping away. The long-awaited decision in May of Cambridge-based microchip designer Arm Holdings to list on Nasdaq rather than London was a bellwether moment.

Arm was already owned by Softbank of Japan, so its Nasdaq choice always looked likely – despite lobbying on London’s behalf by prime minister Rishi Sunak.

Nevertheless, the Arm story focused a spotlight on a trend that had already seen building materials group CRH, plumbing equipment supplier Ferguson and online gambling group Flutter shift towards primary listings in New York, provoking the media to search for other likely candidates.

A Financial Times feature in late May suggested a fistful of major London-listed names – from British American Tobacco, Barclays and BAE Systems to Diageo, National Grid and Rio Tinto – as ‘companies for which a transatlantic float would be most plausible’ on the grounds that they have significant proportions of US shareholders and revenues and are undervalued relative to US competitors.

[See also: why are wealth firms ignoring their own advice?]

‘Reform agenda progressing on all fronts’

The topic is so hot, indeed, that no major public company can afford not to be talking to advisers about the pros and cons of listing elsewhere. IPOs in digital and bioscience sectors are likelier than ever to head straight for Nasdaq, expecting to find like-minded entrepreneurs, sophisticated investors and expert analysts.

How has it come to this? We’ve already had Lord Hill’s 2021 ‘UK Listings Review’ and last year’s ‘Edinburgh Reforms’, designed to drive competitiveness in listings and other services for corporate clients.

Half a dozen current reviews are delving into aspects of the London market regulation and practice, with the Capital Markets Industry Task Force, chaired by LSE chief executive Julia Hoggett, setting the pace.

Most recently, the Financial Conduct Authority has proposed amended listing rules designed to help founders retain control in their companies, by allowing them to hold shares with more voting rights and removing mandatory shareholder votes on large transactions.

Everyone accepts that this debate goes much wider than listing rules.

‘We have to look at all the threads of the ecosystem, including corporate governance issues and the availability of risk capital,’ says the LSE’s Charlie Walker. ‘But the reform agenda is progressing on all fronts, and at pace.’

And it’s a matter of concern for all public companies, not just listing candidates, boiling down to crucial differences of investor mindset and market practice between the UK and the US. On the US side, says Michael McLintock, chair of FTSE 100-listed Associated British Foods,

‘Investors are better informed and they tend to leave you to get on with it. In the UK there tends to be too much second guessing of boards, and the problem is being made much worse by ESG.’

Rupert Soames warms to the same theme, particularly in relation to governance professionals who intervene on behalf of institutional investors: ‘It seems that boards are no longer trusted to manage their own businesses in the shareholder interest, which 99 per cent of them do diligently and well.

I question the wisdom of cooping up 99 chickens for fear that once in 10 years one of them might lay a bad egg.’

Nobody is saying the US has lighter regulation overall – the compliance regime established by the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Act is highly demanding and US justice is fierce.

But its rules are better designed for entrepreneur-led, high-growth businesses and its remuneration culture routinely offers far higher rewards for successful executives, without the familiar British chorus of ‘fat cat’ accusations.

So no wonder companies are thinking of going to America. No wonder also, incidentally, so many others shun stock markets and consign their fate to private equity, a sector that thrives in the UK as the IPO scene shrivels.

One advocate is serial entrepreneur Luke Johnson, who says: ‘It’s not so much that the [London] stock market is failing as that private equity has emerged as a seriously viable alternative.

It offers higher debt levels that can boost returns, lower compliance costs, confidentiality versus public disclosure, and investors who are intensely hands-on.’

[See also: The rise of activist short-sellers]

‘Increasingly risk-averse’

But the more common view is that something big must be done – as in 1983 – to restore the City to its full potential in public as well as private markets. As McLintock says, ‘A decline of the whole London capital market ecosystem is a bad blow for the UK economy.’

Andrew Chapman, head of investment banking at Peel Hunt, goes further: ‘We need reform of both the supply and demand side… quickly and transparently to rebuild the UK listing venue before we lose our position irretrievably, at which point we risk becoming a regional European listing outpost. If the UK is to compete internationally, it needs a means to allow small companies access to long-term risk capital so that we can have the global leading companies of tomorrow, creating the economy we all want and, critically, building the tax cake.’

Measures talked about by Chapman and other practitioners to achieve that transformation include revoking the EU-derived ‘Solvency II’ rules so that UK pension funds and insurance companies rebalance portfolios away from bonds towards equities; encouraging a more active equity culture generally through additional tax breaks; generating research on smaller companies; and attracting UK retail investors to invest in IPOs for their ISAs and SIPPs.

All those ideas imply increased risk for investors, large and small – but there’s also a widely held view that London’s decline has been driven, in effect, by excessive fear of equity exposure.

Pension fund rule changes in Gordon Brown’s era launched what has become a 20-year trajectory of ‘de-equitisation’, leaving institutions holding relatively tiny portions of UK shares within global blue-chip equity portfolios that sit alongside huge holdings of bonds.

[See also: Wealth managers’ top 2023 calls: Riding the recession]

Only a very reduced population of specialist fund managers look at smaller UK companies, not least because investment banks no longer provide the necessary research coverage.

If there’s one bold wraparound solution to all of these deficiencies, it could be the creation, at scale, of a single, powerful equity-heavy growth fund in which smaller pension funds combine forces.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt and City minister Andrew Griffith are both reported to be keen to push sluggish performers in the pension fund sector towards a ‘superfund’ of this kind, while shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves has even suggested that membership might be compulsory.

All of them have adopted the idea from the current Lord Mayor of London, former investment banker Nicholas Lyons, who

eloquently summarises the argument: ‘We’ve become increasingly risk-averse as the defined benefit pension system has been in run-off and [UK pension] funds have focused heavily on bonds and gilts… But we need critical accelerator funding for our growth companies to persuade them to stay and scale in the UK.

For that, we need a pool of capital, ideally £50 billion plus – which in fact only means 5 per cent of the £1 trillion that is expected to be in defined contribution pension funds by 2030.

‘We have good examples to follow in Canada and Australia. Everyone is in support of consolidation of pension funds to help achieve this, including plenty of trustees of sub-scale funds.’

Such a fund would be a core investor in UK IPOs, though by virtue of size it should offer broad risk diversification for its ultimate investors and pension holders. And it would offer high-growth companies access to follow-on capital in subsequent equity rounds.

Lyons also sees it as ‘a play on UK intellectual property – which is the best in the world – in AI and quantum, in fintech, green and renewable tech, and biotech and life science.

Whatever route it takes, I’m confident we’ve launched an idea that’s going to land’.

And there, perhaps, among a wider menu of reforms under discussion, is the big idea for 2023 to match the bold conceptions of Big Bang and the FTSE 100.