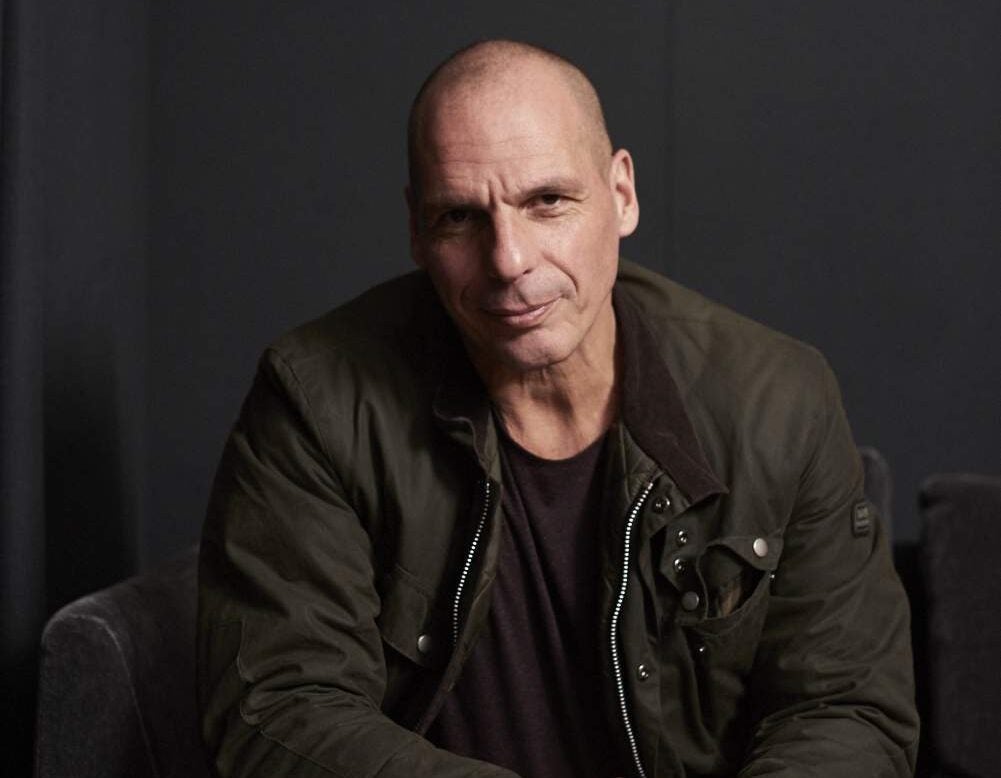

The leather-jacket-wearing economist and former finance minister of Greece talks money, Europe and the future of capitalism with Spear’s editor Alec Marsh

The global economy is in crisis. Capitalism is doomed. Europe is finished. Emmanuel Macron is a spent force. Angela Merkel is out. The Left is a shambles. The rich are afraid. A few short minutes in the company of Yanis Varoufakis – the charismatic, motorcycling former finance minister of Greece – and wow, suddenly everything doesn’t seem so bad.

So let’s begin with the global economic crisis: ‘We have really not recovered from 2008,’ states the 56-year-old. ‘Anybody who thinks that we have is indulging in some quite dangerous wishful thinking.’

Sitting in the chic café of a Covent Garden hotel, the softly spoken economist orders green tea and proceeds to offer the simple explanation, which lasts several minutes and goes like this: the Bretton Woods agreement of 1944, which underpinned the international economic order until about 1970, saw the surplus wealth of the US drive the global economy – a role he describes as the ‘great recycler’ – by taking money from America and investing it, principally in war-trashed Europe and Japan. This came unstuck when the US slipped from being a surplus nation to a deficit nation in the 1970s – when it bought more than it sold – at which point the Americans ‘closed the loop’ on the financial imbalance by sucking the money it was now spending overseas back into Wall Street. This phase sees Uncle Sam play the role of ‘great vacuum cleaner’. ‘That required a net transfer to Wall Street from the rest of the world of about $5 billion a day. Every single day.’

The City of London had a good run at that, too, paying for the UK’s own deficits in a similar fashion. All of which built up bubbles of financialisation – bubbles that went pop in 2008. ‘A market mechanism, if it works well, equilibrates demand and supply,’ he explains. ‘But [this] was an increasing balanced burgeoning disequilibrium. It sounds like a paradox, but it’s the only way I can describe it. It was always going to blow up.’ And blow up it did, taking the world economy with it and sending, among others, the debts of Greece to 180 per cent of GDP.

A decade on, the world is still in the soup. ‘Our global economy is for the first time since 1950 in a situation where there is no clear engine for creating demand, and no one is at the helm,’ declares Varoufakis. ‘We need a new Bretton Woods,’ he adds. ‘But without the United States, it won’t happen.’ And that’s the problem: ‘I do not like to demonise Trump like everybody else on the Left does, but the American Establishment is all over the place, and the poor Chinese… I feel sorry for the Chinese, because the Chinese understand.’ Nor is there any leadership from the EU. ‘Europe doesn’t exist,’ he says. ‘There is no Europe – gone, finished. Macron is a spent force. Merkel is out.’

Which means there’s a void where the decision-making needs to be. It’s not impossible, as shown by the G20 in 2009, when coordinated efforts of the various governments helped to refloat the world economy in the aftermath of the crisis, but that was a one-off. That saw central banks in the US, UK, Japan and China open the taps on spending. (Varoufakis is scathing about the European Central Bank, which began its quantitative easing programme in 2015: ‘Pathetic – that is why you had EU immigration [to the UK], because of the lack of synchronicity between monetary policy here and there.’)

Today there’s still the problem of idle savings and too little investment in the West, which are weighing down on productivity and incomes, especially in the UK. ‘We need to get back together again and create an aggregate investment policy, because the Chinese are investing too much and we are investing too little. That needs balancing, and it has to be done on the basis of an agreement.’

The solution he favours echoes that proposed by the Colossus of 20th-century economics, John Maynard Keynes, whose answer to the financial imbalances of a different age was kiboshed at Bretton Woods by the US, who instead forced through a dollar-based system with organisations such as the IMF. ‘I am adapting it to a world with floating exchange rates,’ explains Varoufakis. ‘We can have the IMF, or something like it, operating as a clearing unit. All trade can go through it in a digital way, with one common accounting unit. That way you could have a common fund solution, which is then used for investment purposes in the deficit areas.’

Without such a system, Varoufakis predicts, we’ll be stuck with a ‘transforming, ever-mutating crisis’. Take the current situation: ‘It began as a recession in the West, then morphed in central Europe as a deflationary period. Deflationary forces have ravaged [Germany] – the negative interest rates are shrinking the savings of the average housewife [presumably including those of Mrs Merkel, the thrifty Swabian housewife]. That’s what’s led to the new fascists rising,’ he continues, his hand forming a raised claw. ‘Deflationary periods always create political monsters.’

Which brings us to his latest venture: DiEM 25, which describes itself as a pan-European political movement and will field candidates in 2019’s European elections. And it brings us to his new role, one – when he’s not writing books on the financial crisis, the latest being Adults in the Room: My Battle with Europe’s Deep Establishment (a title he credits to IMF head Christine Lagarde), or indeed on economics (Talking to My Daughter about the Economy) – that he’s reluctant to admit to. Does he describe himself as a politician? Varoufakis hesitates. ‘Now,’ he says finally, ‘I say yes.’ He’s mid-pose for his picture; the photographer snaps off some frames. Varoufakis looks over. ‘I don’t like the term.’ He goes back to the lens: ‘I am a bad politician, how about that?’

He does not like asking for votes, nor fundraising, but he confirms that he’ll be running in 2019. ‘I’m not sure which country I will be in yet,’ he says. ‘Because we are trying to subvert the dominant paradigm — we are thinking of cross-posting our candidates, so a Greek running in Germany, a German in Greece, in order to highlight the transnationality of the movement.’

A founder of the group, Varoufakis is convinced – not least through the grim experience of being finance minister of Greece for 162 days in 2015 and negotiating with the ECB, IMF and Brussels to stave off what he regarded as punitive austerity in Greece – that the EU is kaput. ‘The European Union sucks,’ he says. ‘There’s no doubt about that.’ And now he wants to fix it. Citing Brexit, Grexit and the collapse of the political centre across Europe, he says: ‘We need a systemic answer to this systemic crisis.’ The movement has now come up with an 80-page European New Deal to do just that, and they’ll be taking it ‘to a polling station near you’.

Except it won’t be coming to any of us in the UK – and nor should it: ‘My message to my friends on the Left and the centre, and even to Remainers within the Tory party, is let’s move on. That was lost. Get over it. Because we are democrats we cannot fathom doing to the Brits what the European Union did to the Irish after the Lisbon Treaty referendum.’

As someone bloodied in his country’s David and Goliath battles with Brussels and Berlin, how would he handle Brexit? ‘Theresa May is mad to be conducting negotiations with Mr Barnier and Juncker,’ he says. ‘These people don’t have a mandate to negotiate. Send Mr Barnier home and file an application for a five-year EEA agreement to begin at the end of the two-year post-Article 50 period.’ Temporary adoption of the Norway model would give the House of Commons plenty of time to mull over future arrangements and Merkel a chance ‘to breathe a sign of relief’. That’s what he calls his ‘small-c conservative Brexit strategy’.

Finally, it’s time to ask this Dr Martens-wearing graduate of Essex University about one more topic dear to his heart: capitalism. ‘The capitalist system is going to be obsolete quite soon,’ he predicts. How soon – 50 years, 100 years? ‘It could be ten,’ he replies. ‘Who knows? It will probably outlive me and my children. But I don’t believe that capitalism is a natural system for organising life. It’s highly inefficient.’

He concedes that it ‘produced all the technologies, gadgets and the goodies that liberated us, but at the same time’, he says, but ‘capitalism is creating AI and 3D printers and so on, that will make [it] obsolete’.

The good news is that his definition of capitalism is strictly Marxist – so private ownership goes merrily on, and so will buying and selling. ‘That’s markets,’ he says. ‘Capitalism is a mode of production where those who own do not work, and those who work do not own.’

His view is that technological changes are reducing the commercial advantages of economies of scale, so the division of labour and capital can blur over time. With 3D printing, each of us can become an industrialist at the press of a button. ‘I’m not against wealth,’ the self-proclaimed libertarian Marxist confides, in a comment worthy of Peter Mandelson’s remark about being ‘intensely relaxed about people getting filthy rich’. ‘I know quite a few wealthy people. What strikes me about them is how increasingly uncertain and insecure they feel.’ Take philanthropy: ‘They’re trying to give their money away. They try to find good causes, but the problem is that philanthropy does not help mend the architectural design faults of capitalism. It may make you feel better, but it doesn’t solve the root cause of the problem.’ This, he believes, is because we are still in crisis: ‘Since 2008, capitalism has not regained its poise, it is in retreat everywhere, you have relocalisation, you have political monsters.’

And suddenly, just as we began, we’re back at surveying the demons of 2008. With that, our time is up. The world’s favourite maverick economist extends a hand and bids us a warm farewell. It’s time to go to Oxford, to address the union. An Athenian philosopher of a different age, Socrates, was put to death for corrupting the young. Quite what they’ll make of this Keynesian libertarian Marxist, one who counts former Chancellor Norman Lamont among his friends, is hard to tell. But hemlock might not be strong enough.

Alec Marsh is editor of Spear’s

Related

HNWs need to give more, says David Miliband

The Spear’s interview: Norman Lamont, the prophet of Brexit

Interview: Fabian Picardo on why Gibraltar will rock on post-Brexit

The Giver and the Gift: The Caudwells’ war against Lyme disease