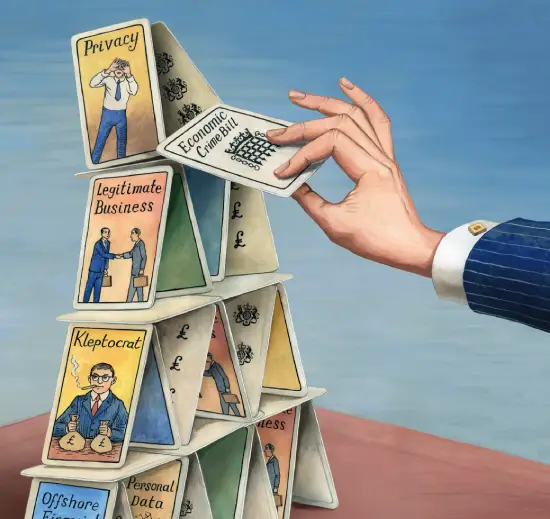

The new Economic Crime Bill means ‘no criminal or kleptocrat will be able to hide behind a UK shell company ever again’, according to the home secretary. But its success rests on the UK’s corporate registrar, Companies House – which already risks toppling under its own weight, says Chris Hawes.

Working out who owns what is tricky. When governments have tried, they have often only succeeded in pushing the answer deeper into the shadows. During the Xia dynasty, when the emperor tried to find out who controlled assets in China, anxious merchants began moving their money out of the country by buying foreign companies and selling goods to their Chinese businesses at hugely inflated prices. Four thousand years later, more complex methods of wealth expatriation have evolved, making modern governments’ task even more difficult.

In 2016, David Cameron announced plans for a public register of foreign-owned property that would require all non-resident landowners to step out from behind the companies holding property on their behalf. Transparency campaigners rejoiced as 40 jurisdictions –including many of the crown dependencies that are often associated with the obfuscation of ownership – were told they would need to disclose the names of clients holding property in Britain.

Then came Brexit. And any issues that would distract the government from delivering the referendum result were kicked down the road. But by February this year, when Vladimir Putin ordered troops to cross the border into Ukraine, the order of priorities had been shuffled once more. The government could no longer ignore the dodgy money washing through Britain’s property market.

In February, Transparency International released a report that revealed £6.7 billion of UK property had been bought by Russians accused of corruption or with links to the Kremlin in the past six years. By March, a new Economic Crime Bill was racing through parliament – including plans for a public register of foreign-owned property and greater powers for law enforcement to investigate unexplained wealth.

According to the home secretary Priti Patel, the Economic Crime Bill would ensure ‘no criminal or kleptocrat will be able to hide behind a UK shell company ever again’. Others were sceptical, however. Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer pointed to the six-month grace period the bill gave foreign property owners to register. Time enough, the opposition leader said, for kleptocrats to ‘launder their money out of the UK property market and into another safe-haven’.

Beyond Westminster, other detractors pointed out more holes in the bill. The Chartered Institute of Taxation explained that the register would only capture people who hold 25 per cent or more of the shares in a foreign company, making concealing ownership as easy as dividing the property into five equal parts and handing them out among friends.

The introduction of public registries without proper regulation, systematic verification mechanisms, and sanctions enforcement would simply prompt criminals to develop more sophisticated concealment techniques, or move their money elsewhere, thereby increasing the scale of the challenge that beneficial ownership transparency seeks to address.

The World Bank, Beneficial Ownership Transparency white paper, 2020

Meanwhile, multiple backbenchers expressed concern that ‘nominee companies’ or trust arrangements could still be used to hide an owner’s identity. Robert Jenrick, a Conservative MP, explained: ‘If I wanted to conceal the ownership of a property, I would simply set up a shell company in the British Virgin Islands through a nominee, in which case, I am sorry to say, all our efforts… would be for naught.’

The Economic Crime Bill received royal assent on 15 March, but the register will not come into effect until at least 1 September – the date by which all overseas property owners will need to submit their details. This may give the government some time to iron out issues. But a bigger wrinkle will persist: the weakness of the registrar, Companies House. Today, Companies House occupies a modern-looking multi-storey office block in the centre of Cardiff, but the institution itself is an artefact of early Victorian capitalism.

Private companies were viewed with suspicion in the early 1800s. The reputational damage done by the collapse of the South Sea Company in 1730 was compounded later in the century by scandals involving the Charitable Corporation and the York Building Society, as former Economist editor-in-chief John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge point out in their book The Company. Edward Thurlow, Lord Chancellor of Great Britain in the late 1700s, encapsulated the feeling towards limited liability companies when he declared that ‘corporations have neither bodies to be punished, nor souls to be condemned, they therefore do as they like’.

While creating a corporation or a company may have had its benefits in the early 1800s, it was an onerous process. Anyone wanting to start a company was forced to leap through hoops, and at exorbitant expense (around £26,000 in modern money), to obtain a private act of parliament or royal charter. As economic innovation accelerated during the early Victorian era, however, demand began to grow for parliament to reform Britain’s vexatious system of company registration.

It was the railways that began to loosen the Gordian knot tying the corporation to the state. To create the industrial Britain that politicians had imagined as Stephenson’s Rocket flew down the Liverpool to Manchester intercity line in October 1829, vast amounts of capital would need to be raised.

Royal charters were issued at unprecedented speed. By the mid-1840s, investors were pouring twice as much capital into the railways as the state was putting into the military, according to Professor Jack Simmons, one of Britain’s pre-eminent transport historians. Ambitious reformers were determined that convention would not stand in the way of this runaway industrial progress. So, in 1844, parliament passed the Joint Stock Companies Act, allowing companies to incorporate simply by registering with Companies House.

The new corporate registrar was set up on London’s Chancery Lane, and the first people through the door would go on to establish the National Savings Bank Association. As well as their £5 administration fee and a copy of their identity forms, the aspiring bankers were obliged to submit any capital raising proposals, advertisements, and even flyers for inspection. ‘The act of 1844 contained controls, many of which are reminiscent of those contained in more modern enactments,’ explains the American economist Leonard W Hein in his paper The British Business Company, pointing to such things as ‘the registration of prospectuses and the maintenance and audit of accounts’.

The administrative burden would soon be regarded as an anchor on Britain’s industrial progress, however, and by 1856 a new bill advocating the streamlining of company formation was travelling through parliament. Standing in the House of Commons, Robert Lowe, the vice-president of the Board of Trade, told MPs to ‘throw no obstacles in the way of incorporation, as it is to the interest of the public as much as for that of the company’. The bill was passed, removing the need for ‘a minimum of paid up capital’, ‘imposed articles of association’ and certain other requirements. The modern corporate registrar had arrived.

Over the following century, Companies House would be buffeted on one side by free-market advocates and on the other by supporters of increased regulation, as it struggled to find an acceptable answer to the corporate oversight equation. After the Second World War, the decline of the British Empire and the creeping globalisation of business made the job even more difficult.

Former imperial outposts such as the Marshall Islands and Seychelles began to recast themselves as financial service satellites, allowing foreigners to incorporate companies within their borders without disclosing their identities. These corporations could then themselves be used as directors to incorporate companies elsewhere, effectively allowing people to purchase property anonymously through labyrinthine corporate structures.

Companies House was now facing something entirely new. When parliament aggressively deregulated in the mid-1800s, one commentator remarked: ‘Seven people each holding a farthing share could now become a corporation.’ By the late 20th century, these people would each be in different jurisdictions, hiding their far-things behind opaque corporations.

Then came the digitalisation of corporate registration. Despite the major hurdles to establishing a company having been swept away by the 1856 Act, only 3,869 companies were incorporated in Companies House’s first 50 years. Today, 3,000 are incorporated every 24 hours. Graham Barrow, a financial expert and host of the Dark Money Files podcast, believes 25 per cent of the companies registered on Companies House are ‘suspicious’. He points out that nearly 10 per cent of these companies are registered by UK-resident Romanians, who make up just 0.5 per cent of the population.

In 2013, a whistleblower identified one of these suspicious companies, Lantana Trade, as the keystone in one of the largest money- laundering operations in history. In a report made to the board of Danske Bank, Denmark’s biggest bank, the whistleblower alleged that billions of dollars had been laundered through thousands of registered corporations such as Lantana. While the whistleblower alleged that the family of Putin were the ultimate beneficial owners of these corporations, the directors listed on Companies House were two firms domiciled in the Seychelles and Marshall Islands. A Kremlin spokesperson told the FT that Putin had no association with the bank.

The whistleblower concluded his report by telling Danske’s board members that UK limited partnerships (LPs) such as Lantana were the preferred vehicle for non-resident clients’. But it isn’t just foreign money being laundered through British LPs. A recent autopsy of Britain’s financial response to Covid-19 revealed that between £3.5 billion and £4.7 billion of the UK’s £47 billion bounce-back loan scheme had been awarded to fraudulent companies. The bungling of the scheme led Lord Agnew, who had served as a government minister, to brand it ‘one of the most colossal cock-ups in recent government management’.

The Economic Crime Bill and register of beneficial owners of overseas entities owning UK property is designed to prevent this kind of snafu. But the scale of the task is enormous. There are nearly 95,000 properties in England and Wales owned by foreign companies, according to re-search by Transparency International. Of those, 85,000 are owned by companies registered in jurisdictions where owners are not obliged to publish their names.

To achieve its planned overhaul of the way company information is held, the government is setting aside £63 million for the reform of Companies House. While this is four and a half times Companies House’s annual budget of £14.5 million in 2020, it is still 93 times less than what organised fraud costs Britain each year, according to Home Office statistics.

This simply is not enough to establish and run a register of this size, says Chris Thorpe, chief technical officer at the Chartered Institute of Taxation. Instead, Thorpe suggests raising additional funds by increasing the cost of registering a company and pumping the surplus back into the institution. Registering a company online currently costs just £12. Increasing this to, say, £100 would add roughly £96 million to Companies House coffers per year, assuming registrants were willing to pay up.

Another way of making reforms more effective could be to tighten the scope of who is captured by the register. ‘What you could do is have a de minimis,’ explains Thorpe. ‘You could quite easily put a minimum value on the houses that have to register, which would immediately take a vast proportion of the risk-free properties out of the firing line.’ This would leave most foreign HNWs with property in England and Wales within the scope of the register but would also mean Companies House had less data to collect, store and protect.

A more radical move to relieve the burden placed on Companies House by the Economic Crime Bill, would be to shift the burden of validating beneficial ownership on to companies. In Slovakia, the government requires that firms owning property in the country register with an authorised third party, such as a lawyer or bank, that has a registered place of business in the Slovak republic. These third parties are then made jointly liable for the veracity of the disclosures, requiring them to underwrite any fines levied against companies that have misreported.

Ensuring Companies House and other law enforcement agencies have the bandwidth to scrutinise the register is essential. In 2020, the World Bank raised concerns that ‘the introduction of public registries without proper regulation, systematic verification mechanisms, and sanctions enforcement would simply prompt criminals to develop more sophisticated concealment techniques, or move their money elsewhere, thereby increasing the scale of the challenge that beneficial ownership transparency seeks to address’.

The Economic Crime Bill could also end up punishing people who use the system legitimately. ‘I have very private clients who don’t want details of their property investments to be public for a range of very valid reasons,’ says Alex Ruffel, a partner at Irwin Mitchell. One example she gives is a client who wants to protect their children because they live in countries with a high rate of kidnappings. Publishing details of their wealth puts them at greater risk, she explains.

While individuals can request that Companies House keep certain data private, the disclosure of information which, while on its own may seem innocuous, can be used in conjunction with other sources. ‘Data mosaics’, as they are known, are useful tools for analysing trends such as gender pay gaps which are built from disparate data sources.

But the technique can also be exploited for nefarious means. Knowing where a professional footballer lives and what time they will be on the pitch is a basic version that burglars are increasingly using. More complicated data mosaics can integrate social media and mobile activity to extrapolate more detailed pictures of people’s lives. If the register doesn’t provide her clients with more protection, Ruffel believes ‘their only option will be to sell’ and take their business interests away from the UK.

James Quarmby, head of private wealth at law firm Stephenson Harwood, believes that as well as enabling identity theft, the Economic Crime Bill (and the register, in particular) could also have a severe impact on the crown dependencies. ‘This is exactly what they feared,’ he explains. ‘It means that you don’t want to hold UK real estate in any kind of trust structure if you want some privacy, because any information will be out there.’

Whether the public register will lead to HNWs selling property and moving assets will become clearer as the 1 September registration date draws closer. Until the government can strengthen Companies House, however, legitimate businesses and the people behind them – not kleptocrats, nor money launderers – may be the ones who bear the brunt of these reforms.

Image Credits: Illustration by Martin Hargreaves; Image of Westminster supplied by AR Pictures