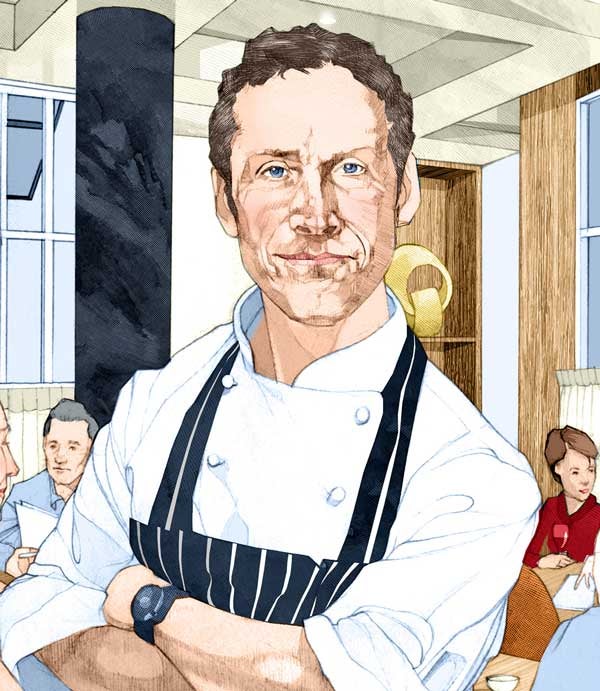

After dropping anchor at the Square for 25 years, chef Phil Howard has launched a new venture in Chelsea. Plain sailing for a man of his skill, surely, writes William Sitwell.

Phil Howard, lean, fit-looking, sharp-eyed and George Clooney-handsome at 50, is pondering the dining room at his new restaurant in Chelsea. ‘It’s developing a soul,’ he says. Formerly the domain of Tom Aikens (whose name is immortally carved above the kitchen stove downstairs), after a refurb the place is a light and airy room decorated with attractive modern art and colourful chairs.

This is Elystan Street, where Howard has landed after selling the Square, which he ran with restaurateur Nigel Platts-Martin for 25 years. Now with his other business partner Rebecca Mascarenhas (with whom he has interests in three other restaurants: the Ledbury, Kitchen W8 and Sonny’s Kitchen) he has left the hedge-funders and Mayfair set for a new clientele on a quiet residential street around the corner from the famous Michelin building.

As Howard has no intention of easing off the throttle at the stove, Mascarenhas is his perfect match. ‘She’s an active business partner,’ he says. ‘I don’t want the responsibility of running the show so she takes care of all the shit, which leaves me free to be in the kitchen or not here.’

Howard is a keen skier, so come winter if the kitchen is running smoothly he’ll have an eye on the Alpine snow reports so he can make an escape, with his wife and two children, to a chalet he owns.

While he does make occasional forays into the TV world on shows such as Great British Menu, the past 25 years have seen him quietly building a formidable reputation as the man behind one of the capital’s most consistently good and popular fine dining establishments. And the Square has reflected the ebb and flow of the London economy.

‘It was a great business for a vast number of years,’ says Howard. ‘We achieved what no other restaurant could: high cover numbers and high average spend. The first fifteen years saw a heaving lunch trade, but then the crash happened of 2008 and it was no longer appropriate for business people to get mullered at lunchtime. Our lunch trade never recovered.’

The arrival on the dining scene of more casual places made it apposite to put a name like Hawksmoor, rather than the Square, on a receipt, even if the spend was the same. ‘In the end,’ says Howard, ‘we were pissing into an increasingly strong wind.’ So after yet another approach from a potential buyer — this time from Marlon Abela’s restaurant business, owner of Umu and the Greenhouse among others — Howard and Platts-Martin decided to sell. ‘I really hope he nails it,’ Howard says of Abela, ‘and I hope he can give it a whole new lease of life.’

Meanwhile, Howard seems to have reached a moment of calm reflection, a happy crossroads as he finishes a 25-year chunk of his life. He was made head chef of the Square on the recommendation of Marco Pierre White, Platts-Martin’s business partner of White’s famous early late-Eighties restaurant Harvey’s. Howard had worked for White at a period when he was, in his words, ‘in his prime’.

‘It was amazing,’ he says. ‘It was everything. I used to stand in that small, shitty kitchen out of which came the most spellbinding cooking. Everything was cooked to perfection down to the last second. It was bloody hard work and I was a valuable member of the team.’

Of course Howard, like virtually everyone else, became a victim of White’s famous temperament. ‘I was sacked. In fact, people were sacked before they walked through the door. And it was never rational. It was one of those nights when Marco entered the dark side. My pomme purée went gloopy, a bit like porridge. So he told me, “Fuck off and don’t come back.”

‘I was livid. It was not in the interest of our customers and I’d worked six days a week — plus Sundays to do photography for his book — for nine months and there was no sense in it. The next day I called him and challenged him, and although I didn’t go back, I think he respected me for it.’

In due course White recommended him to Platts-Martin. ‘It was a brave move by Nigel,’ says Howard. ‘I’d been cooking for just three years, had only reached the level of chef de partie [section head of a kitchen], and I’d never spoken to a supplier or put an order in. But I had no kind of anxiety. I was in blissful ignorance and it was super-exciting. What I lacked in experience I made up for in enthusiasm and energy, and I worked seven days a week.’

Howard had caught the cooking bug while studying microbiology at the University of Kent. He lived with some older foodie students and they used to take their cooking and eating seriously. ‘I knew immediately that this would be an important part of my life.’ And while he ‘enjoyed the brilliance of modern science’, he found himself more often than not ‘distracted… and smoked far too much weed’. He finally left with a third.

He immediately got work cooking in the Dordogne and then, returning to London, found a job cooking smart corporate lunches for the Roux brothers’ catering business. It wasn’t long before he arrived at Harvey’s.

As he cooked through his twenties, those long hours at the Square came at a price. His energy became fuelled by something other than natural youthful enthusiasm. ‘I had a hugely demanding job, a wife and very young daughter at home and a massive problem with drugs,’ he recalls. ‘Addiction takes you to a very dark place. But I was lucky that I got to a point where I thought, “I’m going to go down the swanny.”’

After a struggle, rehab and the support of Nigel Platts-Martin, he got on top of the problem and now recalls that he’s happily brought up two children without a hangover.

Today, as he opens a new restaurant, the main issue he tries to grapple with is the wellbeing of the planet. ‘There is an issue in that many people are starving and here I am peeling the tails off langoustine, but that’s what I do,’ he says. ‘So I try to operate as responsibly as I can. We are as green as we can be in the kitchen. We compost everything, we rely less on proteins, there are far more vegetarian dishes on the menu and the portions are smaller.’

In the kitchen on the day I visit, grouse are being prepared and will be served with crispy spring rolls filled with autumn vegetables. The menu also features roasted vegetables with a cashew hummus, curry oil and shallots, as well as hand-rolled ink linguine with a sardine vinaigrette. It is technically and visually immaculate but not over-fussy food. Howard’s vision is simply to deliver pleasure. And when the restaurant settles and finds its soul (he’s currently working seven days a week) he’ll indulge in his passion, his love of the mountains and go skiing: ‘Great therapy for a life in a stainless steel box,’ he says of kitchen work. ‘I haven’t been this happy for as very long time.’ The people of Chelsea should count themselves very fortunate indeed.