After a series of scandals and poor decisions, one of the great names of Swiss banking is teetering on a precipice. Now, with a new CEO and a new plan, can Credit Suisse come back from the brink? By Martin Vander Weyer

Can Credit Suisse survive? There were moments in 2022 when serious observers thought the 166-year-old Swiss institution could not; some even muttered that it did not deserve to.

By November the share price was on the floor – around $3, having stood above $20 in recent memory – as directors warned of a fourth-quarter $1.6 billion loss and revealed a breathtaking $88 billion outflow of client funds.

But by early December, a fully underwritten rights issue accompanied by energetic media work from chairman Axel Lehmann and newish chief executive Ulrich Körner succeeded, for the time being, in steadying the ship. The outflow (which they blamed on social media gossip) had been stemmed – they said – and key shareholders, though ‘impatient’, had accepted the logic of a radical restructuring, de-risking and cost-cutting programme unveiled by Körner.

The balance sheet after the rights issue would be as strong as those of most European peers, with a ‘common equity tier 1’ ratio above 13.5 per cent. Recovery was not just possible but planned in detail and ready to happen.

Some long-time CS watchers, particularly in Switzerland, accepted that narrative, though they expected a very different (and more Swiss) version of CS to emerge from the wreckage.

Others – more likely to be found in London and New York, including hedge fund managers who specialise in shorting stocks of companies they perceive to be failing – emphatically did not. The best to be said at the time of writing is that CS’s fate hangs in the balance.

How on earth did this former pillar of Zurich’s and Europe’s financial establishment, categorised by the Financial Stability Board as one of 30 ‘global systemically important banks’, contrive so dramatically to diminish its reputation and shareholder value?

The answer, in one sense, is very Swiss: this is a story of a slow-burning culture clash between Switzerland’s traditional virtues of financial caution, discretion, reliability and (let’s be honest) dullness on one side, and the riskier, more lucrative temptations of the American investment banking model on the other.

In another sense, it is a universal parable of early-21st-century commercial banking: CS is just one of many once respected institutions drawn beyond their competence into areas of lending, trading and deal making whose risks they did not understand – until it was too late.

Credit Suisse: A chequered history

Credit Suisse not only fits the Swiss national stereotype; it helped create it. The bank traces its origins to 1856, soon after the adoption of Switzerland’s federal constitution and the introduction of the Swiss franc as its common currency – in an era when the mountainous country was beginning to shift from an agricultural to an industrial economy.

Zurich politician and business leader Alfred Escher (1819-82), seeking finance for ambitious railway projects, decided to found his own bank for the purpose. This was Schweizerische Kreditanstalt, meaning ‘swiss credit institution’ and translating into French as Credit Suisse, which in modern times became the sole name and brand.

Escher’s venture opened a New York representative office in 1870, built a domestic branch network and grew within a generation to be Switzerland’s largest bank – a position it would hold until the 1998 merger of numbers two and three, UBS and Swiss Bank Corporation. And during the first half of the 20th century, CS was central to the development of Switzerland’s reputation as a safe haven for foreign money.

After the Second World War, that status acquired negative connotations in the scandal of ‘Nazi gold’ – assets held in Swiss banks that had belonged to Jewish families in Germany but had been appropriated by the Nazis. Though Credit Suisse, Swiss Bank and UBS sought to close the file in 1998 by offering a $600 million settlement of claims brought by the World Jewish Congress, the issue has never entirely faded: in 2020, when a list was discovered in Buenos Aires of ‘12,000 Nazis’ who had lived in Argentina, many were alleged to be CS account-holders.

Likewise, there were repeated allegations – as the Jerusalem Post put it recently after another data leak – of protecting ‘the secret fortunes of dictators, autocrats, spies, human rights abusers, shady businessmen and other clients involved in torture, drug trafficking, money laundering and corruption’.

Then there were US penalties of $5.3 billion for mis-selling mortgage-backed securities before 2008 and $536 million for sanctions-busting in the same period. And multiple fines for tax evasion: in 2014, CS agreed to pay billion $2.6 billion to US authorities for helping US taxpayers hide offshore accounts. Other cases followed in Italy and Germany; most recently, CS faced a $234 million penalty in France.

The bank naturally seeks to play down the sins of both the distant and recent past. ‘We sell safety, not bank secrecy,’ said the then CEO, Tidjane Thiam, in 2018. ‘Being a safe haven in a world that is becoming increasingly dangerous is no bad place to be.’ But the taint lingers, and has contributed to hostile media coverage of CS’s many other troubles in the past decade.

Spear’s 500 2023: Order your copy here

The Americanisation of a Swiss institution

Before reciting them, however, let us go back 60 years to the beginning of the Americanisation that has driven CS’s fate. It was in 1962 that CS began a partnership with the Zurich branch of the Boston-based investment bank White Weld that led to the creation of Credit Suisse White Weld as an early powerhouse of the eurobond market, brilliantly combining US dealmaking skills with Swiss placing power.

When White Weld was acquired by Merrill Lynch in 1978, CS found an even more prestigious new partner in First Boston. ‘Sexier than Goldman in those days’, as one veteran of the firm puts it, First Boston was a market leader and the breeding ground of many of the star bankers of the era.

CSFB in the 1980s was a first-division player in all aspects of investment banking. Its Swiss parent – by now expansively led by Rainer Gut, a former partner of Lazard Freres in New York – basked in reflected glory and made more acquisitions in banking and insurance, followed in 2000 by the $11.5 billion takeover of another Wall Street firm, Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette.

Inevitably in such a spreading empire, there were scandals: notably in the late 1990s, an episode of shredded evidence of malpractice in Japan and the tabloid tale of the flamboyant Flaming Ferraris trading team in London.

Behind the scenes, says the CSFB veteran, the Swiss never really learned how to harness and manage deal-driven Americans who had relatively little loyalty to the firm but heightened appetites for bonuses.

And there was a strong sense that the CSFB tail was increasingly wagging the CS dog: though the CSFB name was dropped when the investment bank became an integral division of CS, it was Illinois-born former CSFB chief Brady Dougan who advanced in 2007 to chief executive of the whole group.

‘Credit Suisse survived the credit crisis of 2008 better than many competitors,’ wrote the Wall Street Journal: crucially, and unlike UBS, it avoided a state bailout. But its scandal sheet was growing, as were internal tensions.

Dougan was succeeded in 2015 by high-flying French-Ivorian Thiam, former CEO of Prudential in London. But rumours said he found small-town Zurich uncongenial – and his tenure ended in 2020 after a bizarre episode in which spies were hired to watch a former colleague with whom Thiam had fallen out.

Next in post as chief executive was a low-profile 20-year CS insider, Thomas Gottstein, promising a ‘clean slate’. Better known as a champion golfer than a banking big-hitter, Gottstein would briefly be paired with a much more exciting appointment from London: ex-Lloyds Banking Group head António Horta-Osório became chairman of CS in April 2021.

2022: Credit Suisse’s annus horribilis

But that year turned into CS’s annus horribilis – matched only by what was to come in 2022. First, a $300 million loss on its exposure to the collapsed supply-chain lender Greensill Capital, which attracted a storm of UK media attention because of the involvement in Greensill of former prime minister David Cameron.

Second, CS accepted large fines from UK and US regulators to settle the so-called ‘tuna bond’ scandal, in which large portions of loans to the government of Mozambique, intended to finance tuna fisheries and other projects, were found to have been corruptly diverted.

Third, and worst of all CS’s disasters, $5.5 billion of losses were incurred on its dealings with Archegos Capital Management, a New York-based family office which defaulted on huge volumes of derivatives contracts taken out as leveraged bets on US and Chinese tech stocks.

A CS internal report blamed the Archegos losses on ‘a fundamental failure of management and controls’ within the bank despite ‘numerous warning signals, including large, persistent limit breaches’. To some analysts, this was the last straw: proof that having fallen below the top bracket in international bank- ing, CS was taking on mediocre, high-risk business and managing it catastrophically.

And if Horta-Osório was the new broom who might have swept the stable, that was not to be either. In January 2022 he resigned after an investigation into alleged breaches of Covid rules, including a trip to Wimbledon to watch tennis – amid rumours that his approach to reform had not been well received by Swiss colleagues.

With the appointment of former Zurich Insurance risk chief Axel Lehmann as chairman to succeed Horta-Osório, the bank was for the first time in many years entirely Swiss-led at the most senior level.

But Gottstein was failing to provide the reassurance investors needed and in July, shortly after announcing a $1.7 billion loss for the second quarter, he was replaced by Ulrich Körner, a former McKinsey consultant (nicknamed ‘Uli the Knife’ for his cost-cutting prowess) who had previously worked for CS before moving to UBS, whose asset management business he ran from 2014 to 2019.

Körner set to work on a plan to turn CS’s fortunes around, essentially by building on its core Swiss banking, asset management and wealth businesses, and shrinking everything else. Unveiled on 27 October, it included a CHF4 billion (£3.5 billion) rights issue, a 15 per cent reduction in the group’s cost base by 2025, a sell-off of risk assets from its ‘securitised products’ division – and the re-creation and spin-out of CS First Boston as an arm’s-length investment bank, to be led by ex-Citi-grouper and CS board member Michael Klein.

The unit revived under the First Boston brand would have ‘a partnership culture’, meaning executives would have equity and it would accept outside capital – though CS declined to say how far it was prepared to be diluted. First to declare potential interest in investing was Bob Diamond, former trading head of Barclays Capital. Soon after, the Wall Street Journal reported that Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman was sizing up a $500 million investment.

It was an eye-catching package, but a rapid survey of City opinion suggests Körner’s performance did not universally impress.

‘He’s a COO at heart, not a CEO,’ says a source who knows him well. One senior trader, watching Körner on Bloomberg, noted: ‘Lacked conviction… If I knew nothing else, I’d be a short seller.’

One investor in that particular line of business took an even dimmer view: ‘CS simply can’t survive as an independent institution. When a franchise like this implodes, it starts slowly then goes much quicker towards the end. That’s what we’re watching now. The rights issue plugs a temporary hole, but that’s all.’

A former UBS executive foresaw survival, but only by a different path: a spin-out of CS’s Swiss retail bank and a forced merger of its wealth management and shrunken investment bank interests, possibly with those of UBS.

Naturally, CS’s leaders are saying nothing at this stage about any plan B, pointing to the unfulfilled merger rumours that swirled around Deutsche Bank at a similar recent low ebb.

The party line from Körner is about creating ‘a new bank that is simpler, more stable and with a more focused business model built around client needs’. Chairman Lehmann adds a statement of the obvious: ‘Credit Suisse is on an important journey. We will work to rebuild and refocus this proud 166-year-old Swiss institution.’

He could hardly have said anything else – but the key word in that second sentence has to be ‘Swiss’.

One Zurich-based financier offers a different perspective: ‘Credit Suisse will take a long time to recover but I believe it will survive because at its core is a good, proper Swiss bank run by very respectable people; being boring’s no bad thing in the end. That core Swiss business is now probably worth more than the whole global CS enterprise. Credit Suisse needs to rediscover true Swissness before it’s too late.’

Credit Suisse: A timeline of banking scandals

1986: Hidden accounts for Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos

The Philippine dictator and his wife used Credit Suisse to hide some of the billions they stole, under the names ‘William Saunders’ and ‘Jane Ryan’.

1999: Japanese ‘shredding party’

Japanese authorities fine the bank and revoke its licence after staff hold a ‘party’ at which they destroy evidence related to an investigation

2004: Yakuza money laundering

A Credit Suisse banker is charged with helping launder yakuza gang money but gets off on the basis he was unaware of the source of the funds

2009: US sanctions breaches

After circumventing US sanctions against various countries between 1995 and 2007, the bank is fined $536 million

2021: Collapse of Archegos

Credit Suisse’s high-risk exposure to the doomed US hedge fund results in a loss of $5.5 billion for the bank

2021: Greensill loans

The collapse of supply-chain lender Greensill Capital forces Credit Suisse to suspend $10 billion of investor funds

2022: Chairman’s Covid quarantine breaches

António Horta-Osório resigns as chairman over breaking quarantine rules in Switzerland and the UK, having been seen at football and tennis matches.

Martin Vander Weyer is business editor of The Spectator

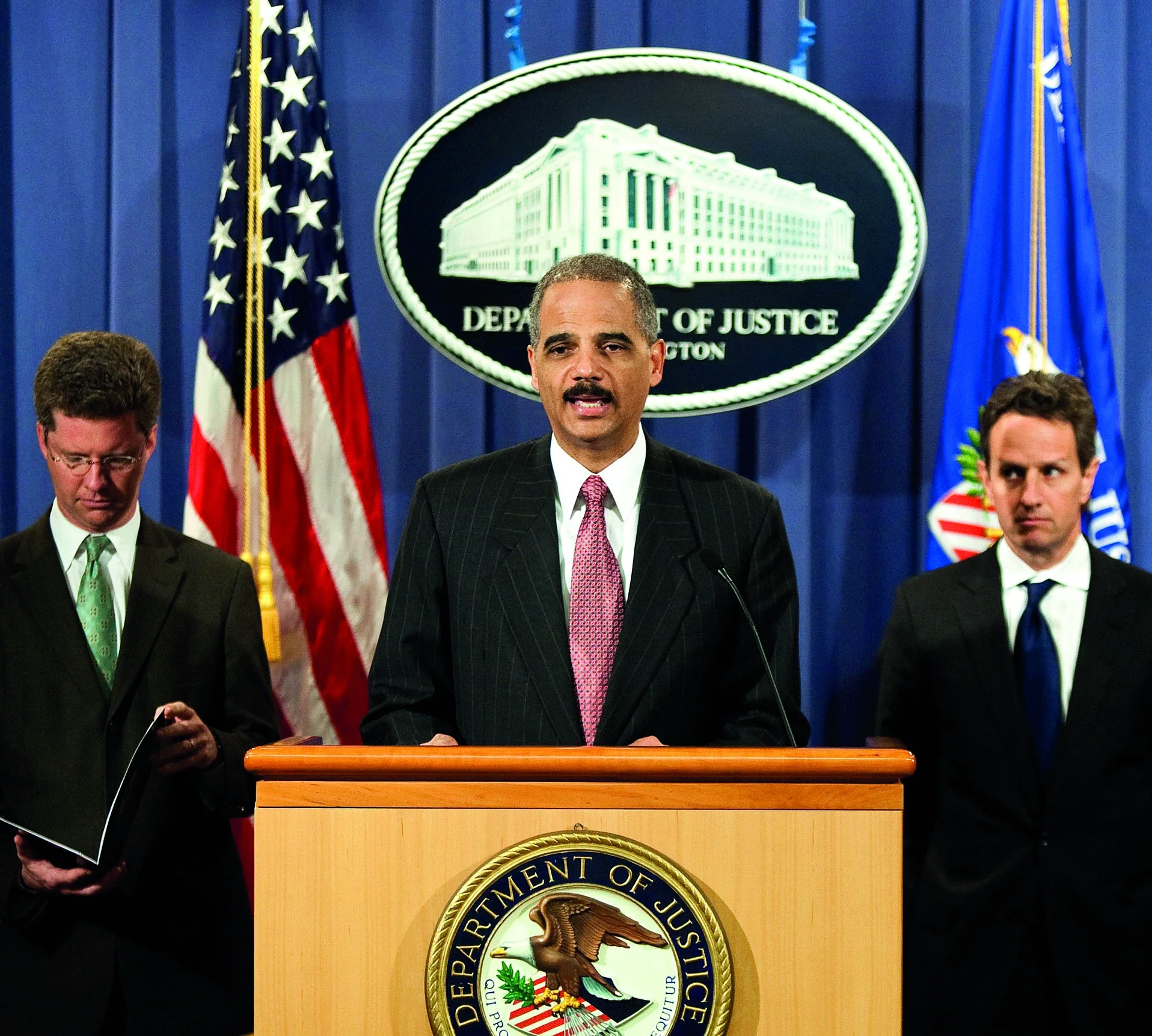

Main image: Bob Venables

More from Spear’s

Analysing the world’s most powerful family-run businesses

The best wealth managers for UHNWs