Peter York on a revealing biography of a man who defined the Establishment, and Christopher Silvester on Michael Lewis’s tale of a duo who reshaped economic thought

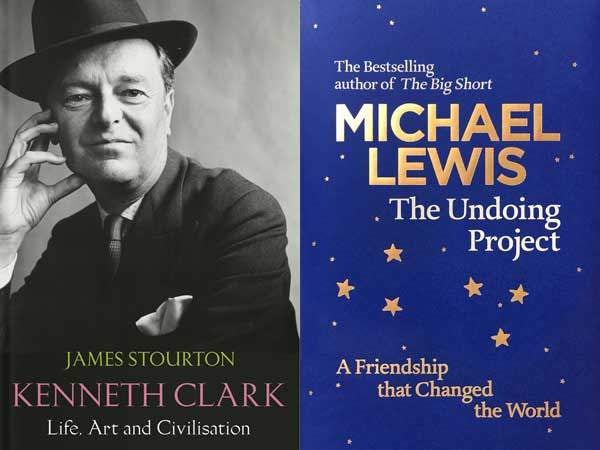

Kenneth Clark: Life, Art and Civilisation by James Stourton

People are always on about ‘the Establishment’ now, saying they’re challenging it (whatever it is — they exactly never tell you). The ‘metropolitan liberal elite’ is a favourite hate word for these latter-day Wat Tyler peasants’ revolt types, horny-handed provincial sons of toil, angry people from Nowhere like… Boris Johnson,

or that notable Rebel Yeller John Whittingdale.

In 1958, when Henry Fairlie published his famous essay on ‘The Establishment’ in the Spectator, it was clear enough. The Establishment then was that group of people who ran the show by consensus. The people — overwhelmingly white, male and upper-middle-class (with a few house-trained toffs and grammar-school meritocrats) — who ran, chaired and boarded the great institutions of state, culture and big mainstream business. People who knew each other, because they (mostly) had been to the same schools and universities. People who knew the form. People who understood the obligations of public service. Connected clubmen.

Kenneth Clark, ‘Lord Clark of Civilisation’, was a favourite example for the postwar world. Garlanded with honours, knighted in 1938, peerage in 1969, chairman of this committee, member of that, chancellor of three universities. Clark’s civilised, civilising mission was in the arts and particularly painting. Director of the National Gallery from 1933 to 1946, Keeper of the King’s Pictures from 1934-45, cataloguer of the Royal Leonardos at Windsor Castle. Urbane, witty, wrote like a dream, Winchester and

Trinity, Oxford.

Also TV star, bestselling author and plutocrat. In 1969 Sir Kenneth Clark, 66, the very model of an Establishment committee man, became nationally — and then internationally — famous as the writer and presenter of a thirteen-part series of one-hour programmes on the new BBC2. In colour. Civilisation was the programme to introduce colour as an ‘upscale’ medium associated with the arts rather than sitcoms and showbiz, the staples of American colour TV. (The Establishment was united in its dislike of American commercially supported colour TV back then.)

Civilisation was the defining prestige TV arts programme and the defining BBC vehicle. It was filmed across Europe and in the USA, the cost to the BBC was the equivalent of £8 million (huge by late-Sixties standards), and it looked ravishing. And all described by a tweed-suited, upper-RP-speaking type who clearly knew everything. An Edwardian, born in 1903 with those precise ‘Rs’ and vowel sounds, the voice that the Establishment recognised as ‘one of us’ and other types would describe as a toff, or a gent.

But Clark’s father, Kenneth MacKenzie Clark, was actually a Scottish plutocrat with a Scottish accent — the great-grandson of a line of textile titans, the Clarks of Paisley, who’d become, by the time Clark was born, the idle rich. People with a shooting estate of 11,000 acres in Suffolk, a yacht, a house in the South of France, and a clutch of Victorian plutocrat pot-boilers on the walls — William Orchardson and Rosa Bonheur, that kind of thing. Cheerful, rich, Edwardian philistines, not remotely greenery-yallery Grosvenor Gallery. Nor, for all the money and acres, remotely toff-assimilated, preferring the company of other Scottish plutocrats and entertainers. But the idle richness, the move to England, the choice of prep and public schools (Wixenford then Winchester, nursery of diplomats, chancellors and clever Our-Crowders), meant young Kenneth was assimilated, gented-up, accented-up, bound for discreet insider glory.

But Clark was an only child, and an arty one, excited by Ruskin and Pater, drawn to the Ballets Russes and Japanese art exhibitions. And, at Oxford, part of the famously infamous Maurice Bowra set of gay Twenties aesthetes, the Anthony Blanche boys. Except not gay, not remotely gay, rather a romantic who loved the company of women and later had a discreet harem of ladies, mainly the wives of nice friends.

Modern biography loves contradictions, people conflicted, haunted by their past, burdened with a dark secret, not what they seem. But James Stourton’s brilliant biography of Clark introduces the contradictions subtly, without excitable signalling. And he layers them, nuances them because he understands the language codes of the class and the period. How Clark could, for instance, say he and his wife Jane were the only ‘middle-class’ couple at dinner with the King and Queen (George VI and Elizabeth) plus a tableful of dukes and earls, when he was actually an experienced Royal familiar by then. Or how he could describe himself as ‘a failure’ and half mean it.

But, for all the brilliant parties in his grand Adam house in Portland Place, he saw himself as the friend of artists rather than aristocrats. And he was never happier than with the 20th-century artists he befriended and sometimes discreetly supported, artists who in turn became stalwarts of the mid-20th-century British arts Establishment: Henry Moore, John Piper and Graham Sutherland. People who met the great world at his table and profited from it.

And was he a cold, ruthless careerist? His friends saw a ‘glass wall’ between him and the world and said they’d never really known him. Or was he a repressed, lonely-only man, who’d weep in front of a transfiguring picture (or rush off to weep in the gents after being faced with his first crowd of American fans, apparently convinced he was a glib fraud)?

Clark often said he’d spent altogether too much time — 40 years or so — on good works committees, rather than writing or teaching. But Stourton makes a good case for Clark as the greatest populariser and enabler of art for all in his generation — the bridge between the old mandarin world and the current one of huge rising audiences for museums and art festivals, of popular TV art and history gurus.

Was Clark a high-minded statist leftie like his Winchester contemporaries Hugh Gaitskell and Richard Crossman, or just a sentimental poseur, protected by his money?

I never met Clark, but I was interested. I did meet his bad-boy son — the Tory MP and serial seducer Alan Clark — and went to Saltwood Castle, Clark’s Kent home. I saw where those final shots from Civilisation were filmed. I didn’t know his harem but a friend is the daughter of his closest lady — he constantly raised and dashed her hopes, and promptly married a woman with a nice château in France when his wife died. (Jane, his wife of 50 years, clever, elegant but often embarrassingly drunk and drugged, died in 1976. She was the central prop and pretext of his life.)

This is the book, layered, nuanced and assiduous, that James Stourton (art history at Cambridge, former UK chairman of Sotheby’s) was born to write.

The Undoing Project: A Friendship That Changed the World by Michael Lewis

In 2015 The Economist listed as the seventh most influential economist in the world a man who had never studied economics as such, let alone held an academic post as an economist. OK, so he was awarded the

2002 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (shared with Vernon L Smith), but Daniel Kahneman was a psychologist

by academic training who specialised in the psychology of judgement and decision-making, and only latterly worked in the field of behavioural economics.

His most groundbreaking work was done in conjunction with another Israeli-born psychologist, Amos Tversky, over a period of about fifteen years, and it is their dyadic intellectual friendship which is the subject of Michael Lewis’s latest book.

A review of Lewis’s 2003 book Moneyball in the New Republic, by economist Richard Thaler and law professor Cass Sunstein, alerted Lewis to the fact that his central argument that ‘any expert’s judgements might be warped by the expert’s own mind’ had been described back in the Seventies and Eighties by Kahneman and Tversky in a series of social science papers that influenced myriad disciplines. Lewis probed further and concluded that Kahneman and Tversky’s friendship and collaboration would make an excellent book in its own right.

Considered the two brightest stars of Tel Aviv’s Hebrew University in the Sixties, both were grandsons of eastern European rabbis. Once they found one another, their relationship became symbiotic. They would talk for hours in private, both in English and Hebrew. ‘From the other side of the door you could sometimes hear them hollering at each other,’ says Lewis, ‘but the most frequent sound to emerge was laughter.’

Yet their personalities were sharply different. Kahneman was a Holocaust kid who recalled what it was like to be a hunted ‘rabbit’, a gloomy loner, awkward in company, and full of self-doubt, while Tversky was ‘a swaggering Sabra — the slang term for a native Israeli’, an extrovert, a joker, and full of self-confidence. ‘Amos was a one-man wrecking-ball for illogical arguments; when Danny heard an illogical argument, he asked, “What might that be true of?”’

Tversky would describe Kahneman as the greatest living psychologist, but the latter’s ‘tendency to look for his own mistakes became the most fantastic material. For it wasn’t just Danny who made those mistakes: Everyone did. It wasn’t just a personal problem; it was a glitch in human nature.’

Human judgement, they found in a series of experiments, was distorted by three heuristics or rules of thumb: representativeness (comparison with existing mental models), availability (something memorable), and anchoring (where people were anchored with totally irrelevant information). We are so often bewitched by experts that we fail to recognise that they too are susceptible to biases and emotional pulls of all sorts. Kahneman and Tversky’s ideas assailed and undid the conventional assumptions of statisticians, theorists of decision making and economists. Indeed, Tversky thought it absurd that the last group had a rational model of economic man, while Kahneman dashed American economists’ beloved utility theory by showing that people sought not to maximise utility but to minimise regret when making economic choices.

There are three undoings in this book. The first was the undoing of conventional theories, as already noted. The second was largely Kahneman’s baby, the elucidation of a fourth ‘simulation’ heuristic, the human obsession with ‘what ifs’, or as Lewis puts

it ‘the power of unrealised possibilities to contaminate people’s minds’. The third undoing was a personal one.

Their collaboration began to undo. Separated geographically, they now communicated mainly by letter and could identify which of them was responsible for which part of their hitherto seamless thought processes. Barbara Tversky overheard their heated phone calls, saying ‘it was worse than a divorce’.

Kahneman had felt overshadowed by Tversky in the eyes of the world, but in the end what mattered most to him was his sense of Tversky’s rejection: ‘I wanted something from him, not from the world.’ When Tversky was diagnosed with a terminal brain tumour, however, Kahneman was still the second person he told.

Lewis deftly interweaves their story with passages explaining how their papers influenced others and fuelled separate collaborations. Few writers could explain Kahneman and Tversky’s experiments and work with the élan that Lewis brings to the task, but it is the psychological insight that makes this book such a stimulating read.